Candice and Kenneth Meisgeier, who call the northeastern Iowa city of Oelwein home, know the state’s mental health care system like the back of their hand, with three of their four children having high-functioning autism.

Her oldest son, who is now 15 years old, was 4 years old when his parents noticed behavioral and developmental issues. At age 6, he had just started kindergarten when the quirks turned into meltdowns where he became violent and inconsolable.

For years, physicians said his behavior resulted from poor parenting. It was clear the physicians were missing something, Candice Meisgeier said. The family was in and out of specialists’ offices getting new diagnoses and medications.

At 7 years old, he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety, and depression by a physician at the University of Iowa.

Under the suggestion of a psychologist, the Meisgeiers admitted her son to Tanager Place, a psychiatric medical institute for children in Cedar Rapids — 71 miles south of the Meisgeiers’ home in Sumner, Iowa, at the time.

“The conflicting emotions that you feel are devastating, but it was a very healing time as we continued to try and find answers,” Candice Meisgeiers said.

Oftentimes, Candice felt as though physicians were just hoping that a diagnosis would stick.

However, the support the Meisgeiers and other families like theirs need is far greater than a diagnosis.

“For years, my husband and I chased that diagnosis,” Candice Meisgeier said. “That diagnosis is nothing but a classification of symptoms. It is not the be-all, end-all.”

Throughout those years of taking her son to various specialists, Candice said the shortest amount of time the Meisgeiers waited to be seen at the UI Hospitals and Clinics was four months. Sometimes, they had to wait up to six or seven months.

The Meisgeiers aren’t alone. With a lack of access to care, many Iowans wait months and may have to travel hours to receive adequate treatment for mental and behavioral health issues.

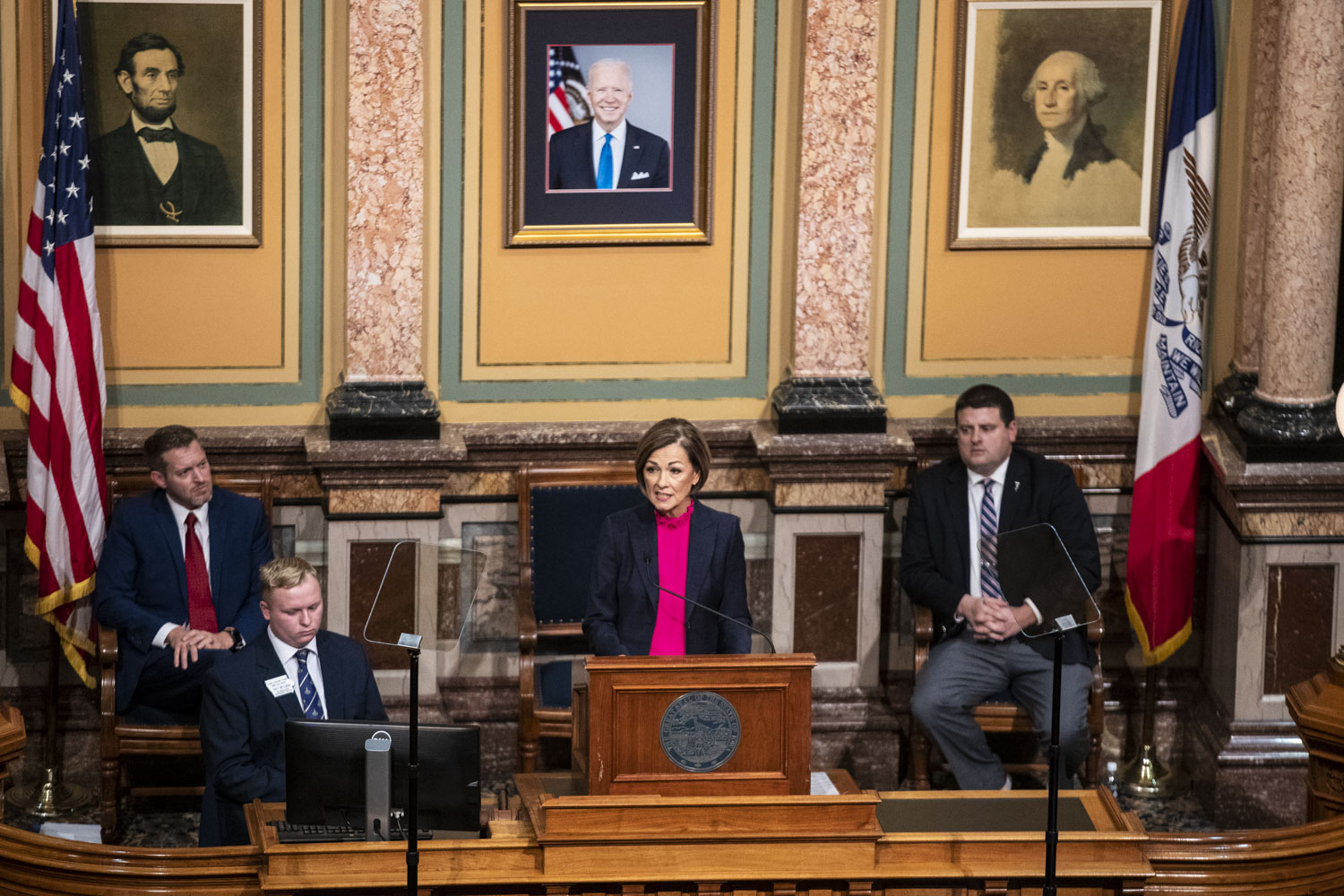

Iowa faces a shortage of hospital beds and mental and behavioral health providers, leaving Iowa’s mental health system overburdened, experts say. With a shortage of providers and a lack of access to inpatient psychiatric care in the state, Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds has proposed combining Iowa’s mental health and substance use disorder treatment districts to provide streamlined care for Iowans.

Senate File 2354 would condense Iowa’s 13 Mental Health and Disability Service regions and 19 Integrated Provider Networks, which provide care for substance abuse disorders, into seven new Behavioral Health Districts, aligning funding and priorities between the two previously separate systems.

Advocates say the realignment will make services easier for Iowans experiencing both mental health and substance use issues, but some worry that the bill is not enough to fix Iowa’s mental health care crisis

With a lack of beds, Iowans lack access to mental health care

According to November 2023 data from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, Iowa has only 30.6 percent of its need for mental health care providers met, with a total of 106 additional providers needed to meet the full demand.

When a patient is released from a psychiatric unit, a follow-up appointment is recommended within two weeks. In Iowa, the average wait time for these appointments is two months.

The Treatment Advocacy Center, a nationwide advocacy group that pushes for reform on severe mental illness services, estimates that 84,067 Iowans have severe mental illness. About 34,875 of those Iowans receive treatment in a given year.

Despite this great need, Iowa only has two state-operated psychiatric hospitals: the Independence Mental Institute in Independence and the Cherokee Mental Health Institute in Cherokee, which operate a combined 64 adult psychiatric inpatient beds and 28 pediatric psychiatric inpatient beds.

The Treatment Advocacy Center states that 50 beds per 100,000 people are required to give what the center describes as minimally adequate treatment for adults with severe mental illness. Iowa falls dangerously short of that recommendation, with only two adult psychiatric inpatient beds per 100,000 people.

In addition to the state-funded beds, data released by the Iowa Department of Health and Human Services in January shows that community hospitals across the state collectively offer 809 licensed psychiatric beds — the number of beds licensed by the state of Iowa — but only 646 of those psychiatric beds have the correct staff-to-patient ratio to be filled.

With only 64 state-funded psychiatric beds and 646 privately staffed inpatient psychiatric beds, Iowa ranks last in the U.S. for state-managed inpatient psychiatric beds to treat adult patients, filling in the 51st spot behind all 49 other states and Washington, D.C.

What does Reynolds’ bill do?

Reynolds’ proposal would condense the state’s 32 mental health and substance use areas into seven new Behavioral Health Districts. The creation of new districts also would combine the mental health and substance use funding streams. Under the proposal, disability services would be moved to the HHS Aging and Disability Network.

Iowa Sen. Mark Costello, R-Imogene, vice chair of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, said Reynolds’ proposal will improve the current system to provide more complete and equitable services.

Costello said the governor’s proposal will benefit mental health care as a whole in the state, but he isn’t sure if it’s directly aimed at increasing the number of psychiatric beds.

“We’ve got different programs to try and meet those needs, we’ve enhanced some routes and are trying to get people to expand those areas,” Costello said. “There’s a lot of things that are in the works that we’ll see … Hopefully, that will bear fruit.”

Iowa Rep. Beth Wessel-Kroeschell, D-Ames, said Reynolds’ proposal won’t make any huge difference, but mental health and substance use districts should have been combined many years ago.

“So many people have both, and not being able to provide services for both of those for one individual has been a problem for many years,” Wessel-Kroeschell said.

How will the bill combat the mental health crisis?

Reynolds’ proposal aims to ensure better coordination for substance abuse and mental health care, as many Iowans seek care from both programs currently. Her plan aims to provide more access to mental health care by optimizing programming and funding to the districts.

Kollin Crompton, a spokesperson for the governor, said mental health care has been one of the governor’s highest priorities since taking office in 2017, but there is still work to be done.

“That’s why Governor Reynolds is focused on building a full continuum of psychiatric care that focuses not only on high-quality state psychiatric hospitals for the most complex needs, but also private psychiatric hospitals, crisis services, and outpatient care,” Crompton said in a statement to The Daily Iowan. “Iowa must also emphasize early interventions and ongoing behavioral health needs to align the entire continuum and ensure Iowans receive the right care, in the right place, at the right time.”

Crompton said 25 percent of adults with serious mental health issues also have substance abuse disorders.

“Currently, Iowa’s mental health and substance use services are coordinated separately, making it difficult for Iowans to get the services they need and for providers to coordinate care,” Crompton said. “By aligning these 32 separate regions into a unified seven, we can improve coordination of services and deliver better treatment to Iowans.”

Mae Hingtgen, CEO of Mental Health and Disability Services of the East Central Region, said combining substance use and mental health treatment has been one of the East Central region’s top priorities.

“They are so intermingled that we think it’s super important that the funding and policy in Iowa are combined so that we can really effectively treat people,” Hingtgen said.

Mary Issah, executive director of the Johnson County chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, is optimistic that Reynolds’ proposal will make a positive difference.

“Hopefully it will help our funding streams come to us a little more easily,” Issah said. “That’s really important because we’ve been in two different silos for so long, we don’t know what the other one’s doing.”

Experts: Bill won’t fix the crisis, but it is a start

While advocates favor combining mental health and substance use treatment, some experts say more must be done to solve the lack of access to mental health care in Iowa.

Barry Schreier, director of the Higher Education Program with the Scanlan Center for School Mental Health and a Professor of Counseling at the UI College of Education, said the state not only lacks psychiatric beds, but access to mental health resources as well.

“It comes down to money and it comes down to priorities,” Schreier said. “We have a value around mental health, but we simply are not valuing it. The way that we show our value of things is we give money and people and space … And we’re not doing any of those things, or an insufficient number.”

Schreier said Iowa’s mental health care system would benefit if the state joined the PSYPACT, or Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact. In this multi-state coalition, licensed psychologists can provide mental health care to any other person in any of the other PSYPACT states.

Iowa has entered similar compacts for nursing, and lawmakers are currently considering a bill to enter a social work compact.

Currently, all states surrounding Iowa are part of PSYPACT. The bill would allow psychologists licensed in a PSYPACT state to perform temporary in-person services in another state and meet with patients in other states remotely without getting licensed in another state. Psychologists would have to be licensed in another state to practice there full-time.

While lawmakers consider measures to improve mental health access in Iowa, Candice and Kenneth Meisgeier have continued to advocate for their son as they navigate Iowa’s overburdened mental health system.

The Meisgeiers have traveled miles upon miles to see psychiatrists, psychologists, and other specialists, waited hours for psychiatric beds to become available, and waited years for someone to diagnose their son.

“That stark reality for people who have and deal with severe mental illness is terrifying, and so sad,” Candice Meisgeier said. “There are weeks where I am crawling just to keep going, and there’s just not enough support. There’s not enough support for these kids. There’s not enough support for the parents and the families. There’s not enough answers, and it’s truly terrifying.”