Bright and early on Sunday mornings during football season, Kinnick Stadium is filled with the rumble of garbage trucks, aluminum cans clinking against each other, and the scrape of hundreds of shovels hitting concrete.

For decades, Iowa City junior and high school student-athletes and musicians, their coaches, and their parents have cleaned Kinnick the day after every home football game.

In return for their help, the University of Iowa pays the Iowa City Athletic Booster Club and the Iowa City Music Auxiliary a set amount per game. The amount is then equally distributed to the different booster clubs in the school district, according to Kristin Pedersen, the director of community relations for the school district.

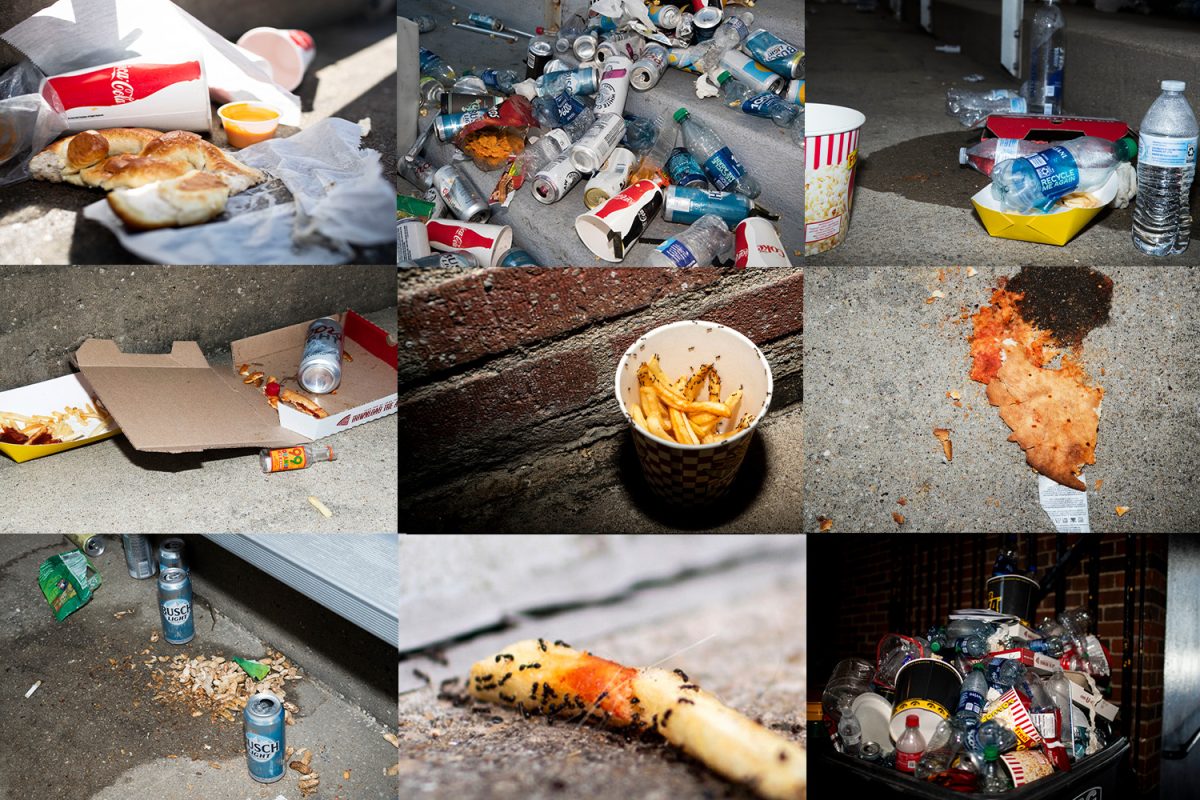

See more of the mess:

Participants all help clean up Kinnick’s seating areas. They split up into different sections, pick up trash, and sort it into different trash bags to be trashed or recycled. The cleanup attendees are armed with shovels, gloves, and leaf blowers to help get the job done.

According to the contract between the Iowa City Athletic Booster Club and the UI obtained by The Daily Iowan, the Iowa City Athletic Booster Club will receive $7,700 per game from the UI for the 2022-23 season. For 2019-21, the booster club received around $2,000 more per game because they also helped clean the stadium after the spring football games, which they will not do this year.

This translates to about $18,000 for each of the three schools for the season. To split up the money to the various sports teams, the three high schools’ athletic directors assess how much funding each team needs and determine how the funds are divided from there, said Angela Rogers, co-president of the Iowa City Athletics Booster Club.

The way the three schools go about the cleanup differs, said Rogers. West High School has every single team come to each cleanup, while City High School and Liberty High School rotate which teams come to clean, she said.

The junior high schools also differ in their methods, said Kelli Taeger, co-president of the Iowa City Athletics Booster Club. Each individual junior high school of the three Iowa City schools comes to two cleanups. For the last game of the season, though, all three junior high schools participate to make the cleanup in colder weather go faster, she said.

According to Damian Simcox, the UI’s associate athletics director for capital projects, this agreement has included West High School and City High School since at least the 1980s, with Liberty High School joining the effort shortly after it opened in 2017.

Payment per game was not increased when Liberty High School was added to the agreement, Simcox said.

Simcox said the cleanup benefits several groups, even ones outside of the Iowa City schools. The aluminum cans collected in the cleanup, for example, are recycled and redeemed, and those funds are donated to Dance Marathon.

The cleanup itself is a group effort that consists of more than just students, coaches, and parents, Simcox said.

Members of the Immanuel Lutheran Church from Washington, Iowa, clean the inside of the stadium and load trash into garbage trucks. ServiceMaster, a cleaning company, cleans the restrooms and assists with picking up trash. The Thursday before events in the stadium, AllSpray, a power washing company, comes in and sprays down the inside of the stadium.

Simcox said these groups on top of the agreement with the Iowa City booster club make the total cost of cleaning up Kinnick Stadium amount to $19,280 per game.

Other ways universities clean

Other Big Ten and Big 12 universities choose to contract cleaning companies or other outside groups to clean their football stadiums after games.

According to Brian Honnold, Iowa State University’s assistant athletics director for facilities and events, Jack Trice Stadium and its paved parking lots are cleaned by Cornerstone Church immediately following a game.

Iowa State pays them $10,000 per game, with an additional $2,000 added for any games that start after 6 p.m. Additionally, Crossroads Baptist Church cleans the grass parking lots around the stadium for around $2,250 per game.

This totals about $12,250 per game and $14,250 for night games. Jack Trice Stadium’s capacity is 61,500, which is about 8,000 less than Kinnick’s capacity of 69,250.

The University of Minnesota also contracts out its cleaning to an outside company, according to Paul Rovnak, the university’s director of communications for athletics.

Minnesota hires a cleaning company named Marsden to do continuous cleanup and trash sorting in all areas except the seating bowl before, during, and after each football game in Huntington Bank Stadium, which has a capacity of 50,805. Minnesota pays Marsden around $40,000 per game for their services.

The day after the game, another cleaning company, Multi Venue Productions, comes in to pick up and sort trash as well as spot-clean the seating bowl. They are paid anywhere from $15,000 to $23,000 for their work. This means that the University of Minnesota pays a total of anywhere from $55,000 to $63,000 per game in cleaning costs.

Michigan State University employs a similar method to the agreement between the UI and Iowa City School athletics. According to Mark Bullion, a media and public information communication manager for the university, university staff as well as a cleaning company help do the cleanup.

The cleaning company also hires out some help from local clubs, organizations, or nonprofits as a fundraiser for those groups, Bullion wrote in an email to the DI. He wrote that Michigan State University spends between $60,000 to $65,000 per game to clean Spartan Stadium, which has a capacity of 74,866.

Parent and student experiences

Some Iowa City high school students, as well as parents, have mixed feelings about the cleanup program.

Grace Bartlett, who is a junior at West High School, said she has participated in cleaning up Kinnick since her freshman year. She is a cheerleader at her high school.

She said attendance for the cleanups has always been made mandatory by her coach, but this was not consistent among different sports teams. For example, she said her brother, who plays on the baseball team, was not required to go to every single cleanup.

Cleaning up the stadium has not always been the most pleasant experience, Bartlett said. She said she has encountered things like vomit and used chewing tobacco while cleaning. However, Bartlett said she is grateful for the fundraising opportunity the program gives her team.

“I’m definitely grateful for the opportunity for fundraising just because sometimes it is very hard for cheer and dance teams, especially just in my experience,” Bartlett said. “We have a hard time sometimes getting funding for things.”

Sebastian Cochran, a UI third-year student who graduated from West High School in 2021, said he was grateful for the funding as well but found some aspects of the cleanup to be unfair to the students.

“I understand why the university and [the Iowa City Community School District] made this the solution because it’s probably the easiest way to get a large number of people to do it,” Cochran said.

Cochran also said he was never personally aware of how the funding was split up among sports teams and was never told an exact dollar amount of how much money his team got as a result of the cleanups.

Isaiah Svoboda, a UI second-year student who went to Iowa City High School, said while his track and baseball coaches verbally mandated students attend the cleanup, this requirement and repercussions for not showing up were not always kept consistent for the entire team or other sports.

He said some of his teammates or other athletes were not expected to show up in the same capacity as other teams, and it came down to coaches on how they enforced participation in the cleanup.

For example, City High School’s band directors require that students come to at least four out of the seven total cleanups unless they have an excused absence, such as religious obligations on Sunday morning, said Mike Kowbel, a band director at the school. If students do not meet the participation expectations, they will be docked points from their grade.

Svoboda said the cleanup does provide an opportunity for the community to get together and bond with people from the other schools. Participants were also provided snacks and treats after they finished cleaning, which Svoboda said he appreciated.

A parent whose child participates in band at one of the Iowa City high schools said they feel that students should not have to clean up the messes of others in order to make sure the activities they like to participate in receive funding.

The DI granted the parent anonymity because of the sensitive details around this topic.

“It’s disheartening to tell young people that they need to fund their art form or sport by acting as the modern-day chimney sweeps in picking up trash left behind by adults at a major stadium event,” the parent said.

Some parents feel the opposite, though, and see the cleanup as a way to make students more conscious of where their trash goes during a game.