UI celebrates 175 years of student voice, protest

As the University of Iowa prepares to celebrate its 175th birthday, The Daily Iowan explores its history through the lens of student voices, social change, and protest.

February 22, 2022

Over the last 175 years, the grassy expanse on either side of the Old Capitol has hosted a wide variety of music concerts, fireworks, and parades. Hundreds of thousands of students have made the lawn a place to study, sunbathe, eat lunch, and people watch.

The events that Iowans typically associate most with the area surrounding the most prominent landmark in Iowa City, however, are protests and debates.

Since its founding in 1847, the University of Iowa has been central for conversation and protest in the state.

From the American civil-rights movement to protests surrounding the Vietnam War and Black Lives Matter, the university has remained a space for students to speak their minds and question authority, said Mary Bennett, special collections coordinator at the State Historical Society of Iowa.

The UI’s Pentacrest remains a central gathering place for protest.

“The Pentacrest has always been the civic center of the campus,” she said. “That’s where the majority of the protests have happened over time.

The UI has helped students find their voices for more than 175 years, which has defined the university throughout its history.

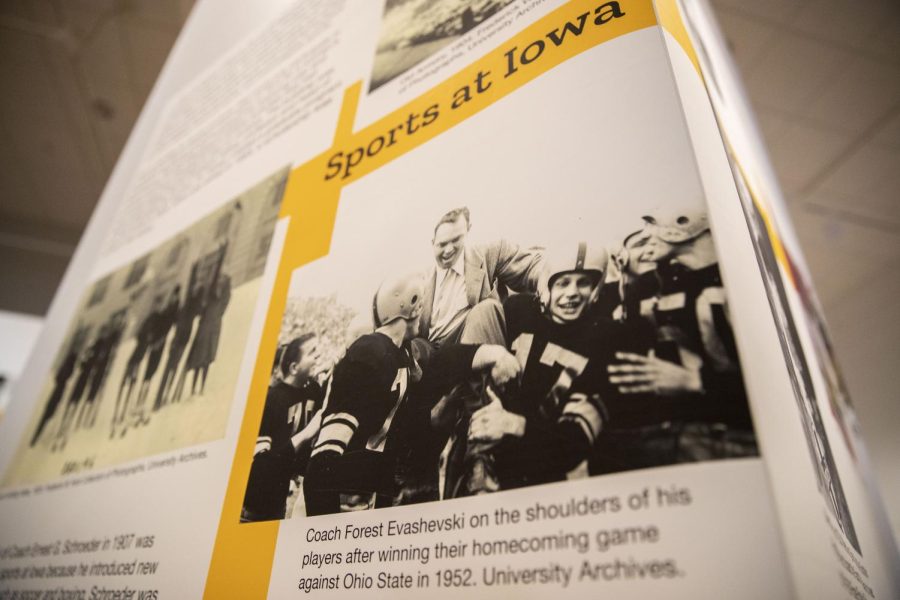

World War II

During the early to mid-decades of the 20th century, the UI saw students protest both world wars.

The university published news bulletins during World War II that proclaimed Iowa City and the UI as “the hub of Iowa’s wartime information wheel,” which was also a space where students voiced opinions and concerns about the war.

Thirty hours after the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, hundreds of UI students packed into MacBride Hall for a student forum. According to the bulletin, students were concerned for their safety and futures.

“For the first time in this student generation, the solid attention of a packed auditorium was focused on the speakers,” the January 1942 bulletin read. “What was being said was re-echoed in the hearts of every one of them.”

Speakers expressed the need to “fight AND learn,” and encouraged “universal hope” for peace. Others voiced concern.

“Wishful thinking will not stop aggression,” then-graduate student Roger Hargrave said at the gathering.

Hargrave had previously served in the Spanish Civil War.

Bill Shoentgen, a then-UI senior from Dubuque and editor of The Daily Iowan, spoke to the students’ upbringing.

“We, the post- and pre-war students, have been brought up in an era of peace,” he said. “We have been educated against imperialistic war. Now peace has been denied to us…The causes of the war make no difference to us, now that war has come. Leave those to history. What does make a difference is that the future is exactly up to us. We must face it.”

Following a declaration of war a few days later, former UI President Virgil Hancher said he believed students should continue their work as normal.

The DI wrote that students “will be ready for the roles — the greatest and the least of them — which we singly and together may be called upon to play,” when it came to the U.S.’s involvement in World War II.

RELATED: University of Iowa history, told through the head Hawks’ eyes

The fight for civil rights

Though wars came and went, the fighting spirits of Iowa students remained, Bennett said.

“The university has always been a place where we bring ideas from all directions and all points of view and we debate their merits,” she said. “… The idea of freedom of speech, questioning authority, asking questions instead of accepting things, has been a major part of the university’s history and spirit.”

Following the conclusion of World War II, students began to speak their minds loudly again during the civil-rights movement.

In the late 1950s and early 60s, pages of the DI were filled with news of civil unrest across the country.

Civil rights leaders visited campus, including Martin Luther King Jr., who came in November 1959.

King spoke in the Iowa Memorial Union about the Black experience, and how people had gone from enslavement to desegregation.

King was quoted in the Nov. 12, 1959, edition of the DI, discussing the forces that stood against integration — including White Citizens Councils, the Ku Klux Klan, and apathetic individuals.

“But in spite of all this, the opponents of desegregation are fighting a losing battle,” he said. “The ‘Old South’ has gone, never to return again.”

King also emphasized the importance of nonviolent protests during his speech. The crowd was “overflowing” during his speech.

A year after King’s visit, a group of students formed the Student Association for Racial Equality, which was affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The civil-rights organization advocated for increased voter registration for Black citizens.

In 1963, several UI students, faculty, and community members backed a telegram to the Iowa Legislature urging them to support civil-rights legislation going through the U.S. Congress.

The UI student body president at the time, Mike Carver, said signing the petition was “a significant step toward the establishment of equal rights for all men.”

The Student Association for Racial Equality sent additional messages to the Iowa delegation in Washington, D.C.

The university also invited Bayard Rustin, a civil-rights leader, to speak on campus, but he was arrested in New York on April 22, 1964 — days before he was set to speak — for protesting at the World’s Fair.

Bennett said the protests and speakers represented “positive growth” for the UI and its student population.

“The protests evolved in a positive way over time,” she said. “There were civil-rights advocates early on in this community and there was a lot of awareness. The Baby Boomer generation was coming to college at this point and ramping everybody up.”

McCartney said student codes of conduct changed drastically in the 60s, as did rules in general.

“In the wake of a number of student protests over this time, there was a great deal of self-examination and reevaluation for the university and its students,” he said. “The civil-rights [movement] drove parts of this. Regardless of it being a predominately white institution, the University of Iowa has a history of students participating in the long civil-rights movement.”

In 1968, Black students occupied the UI president’s office. Two students sat in chairs in the office, showing their dissatisfaction with the university’s handlings of racial equity issues.

“It started with two students, and then eight, and pretty soon the room is entirely full and it’s a standing room,” Bennett said. “They did this as a way to get attention.”

The DI reported on April 10, 1968, that 75 people joined a panel of Black UI community members in the IMU to discuss how white people could aid Black people in the fight for civil rights. The group then drafted specific demands related to the university’s policies on racial equality.

In the wake of King’s April 4 assassination that same year, several students demanded the UI offer Afro-American studies classes, diversify hiring, and aid the underprivileged, Bennett said.

The African American Studies Department was founded two years later.

Vietnam

When another war struck, some of the biggest, and angriest, protests seen on campus took place.

Times were so turbulent that author Larry Perl called former UI President Howard Bowen’s tenure from 1964-69 “years of protest” in his book, Calm and Secure On thy Hill: A Retrospective of the University of Iowa.

The first person to burn a draft card on a college campus, and the second person to do so ever, was Steven Smith, who burned his card on Oct. 20, 1965, at the Iowa Memorial Union in protest of the Vietnam War. Smith was participating in a “Soapbox Stand Off.”

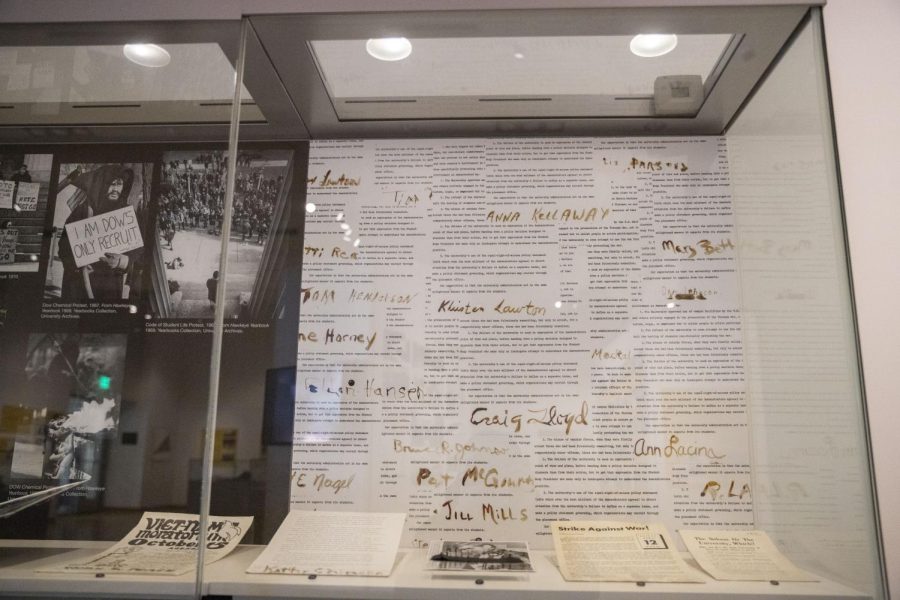

In 1966, roughly 500 UI students pricked their fingers and signed petitions in their own blood regarding the war. A dozen protesters brought the petition into Bowen’s office in the Old Capitol, publicly denouncing the administration’s “complicity” in the war effort. The presence of Marine recruiters on Iowa’s campus also angered the protesters.

However, counter protesters were also present, chanting their support for Bowen and the war, according to Perl’s book.

The Iowa Student Senate found the administration to be “lacking in responsibility” when it arrested some protesters at the demonstrations. The senators asked the university to not take any action against those arrested. The students were questioned, but no charges were officially filed.

Bowen was known during his tenure for being neutral toward the war.

When Willard “Sandy” Boyd took the helm at the UI in 1969, he was met with similar protests. One of the most eventful protests to ever occur on campus followed the 1970 shooting at Kent State University, in which national guard officers shot and killed four students during a protest.

RELATED: ‘It was horrifying’: Revisiting the Kent State shooting’s impact on the UI campus 50 years later

After the killings, Iowa students, like thousands of students across the country, were enraged.

In an interview with the DI in 2020, Boyd — who is now 94 years old — described the harrowing scene on campus following the shooting.

“It was horrifying,” Boyd said. “… [I] lived at home, not in the president’s house, and the day after Kent State, we came out to four [pretend dead] bodies lying in our front yard.”

Demonstrations swelled as students boycotted classes two days after the shooting. That night, 400 people held a sleep-in on the lawn of the Old Capitol, and 50 people broke into the Old Capitol and set off a smoke bomb.

A demonstration May 7-8, 1970, resulted in mass arrests of protesters at Boyd’s request. Days later, he said he regretted the arrests of peaceful protesters.

Protests continued intermittently for years to come, and classes were canceled in 1972 following several protests, including a few where students ended up on Interstate 80.

Bennett said taking to this highway was one of the ways student protests could get on national television, something she believes motivated the decision by protest leaders.

“If they could stop that traffic, even if it was very dangerous, they could make the news,” she said. “Everybody’s got a different opinion about taking to the streets, but they felt like that was the only way to get their voices heard.”

The Des Moines Register reported on May 10, 1972, that 3,000 protesters attended and took to the highway.

On May 9, 1970, the Old Armory Temporary was burned down. On the 10th, Boyd allowed students to leave campus without taking finals, offering them their current grades. Some stayed, others left. In 1972, the DI reported that Iowa ranked second in the nation in increased student protests on college campuses, behind only New York.

The cause of the 1970 fire was never determined, but it was suspected to be arson at the time.

One of the results of these protests was the creation of the student regent position for the Iowa state Board of Regents in 1973. The regents made the decision after students fought for an increased voice in campus decisions.

The in-between years

UI Community and Student Life Archivist Aiden Bettine said fighting authority continued in smaller ways for a few years, following the large Vietnam demonstrations.

“Campus has never been quiet,” he said. “You may not have as many resounding movements that seem as coherent or dominant as the anti-Vietnam protests or IFR [The Iowa Freedom Riders], but there were still protests across time.”

In the 1980s, there were anti-apartheid protests and divestment campaigns surrounding African liberation in South Africa, Bettine said.

“Take Back the Night” protests put women’s liberation on the frontlines as well.

“If you look at a moment, or even a decade, you’ll find protests. You’ll always find protests,” he said. “There may have not been one clear voice always, but no one was quiet.”

Embracing literary opportunities

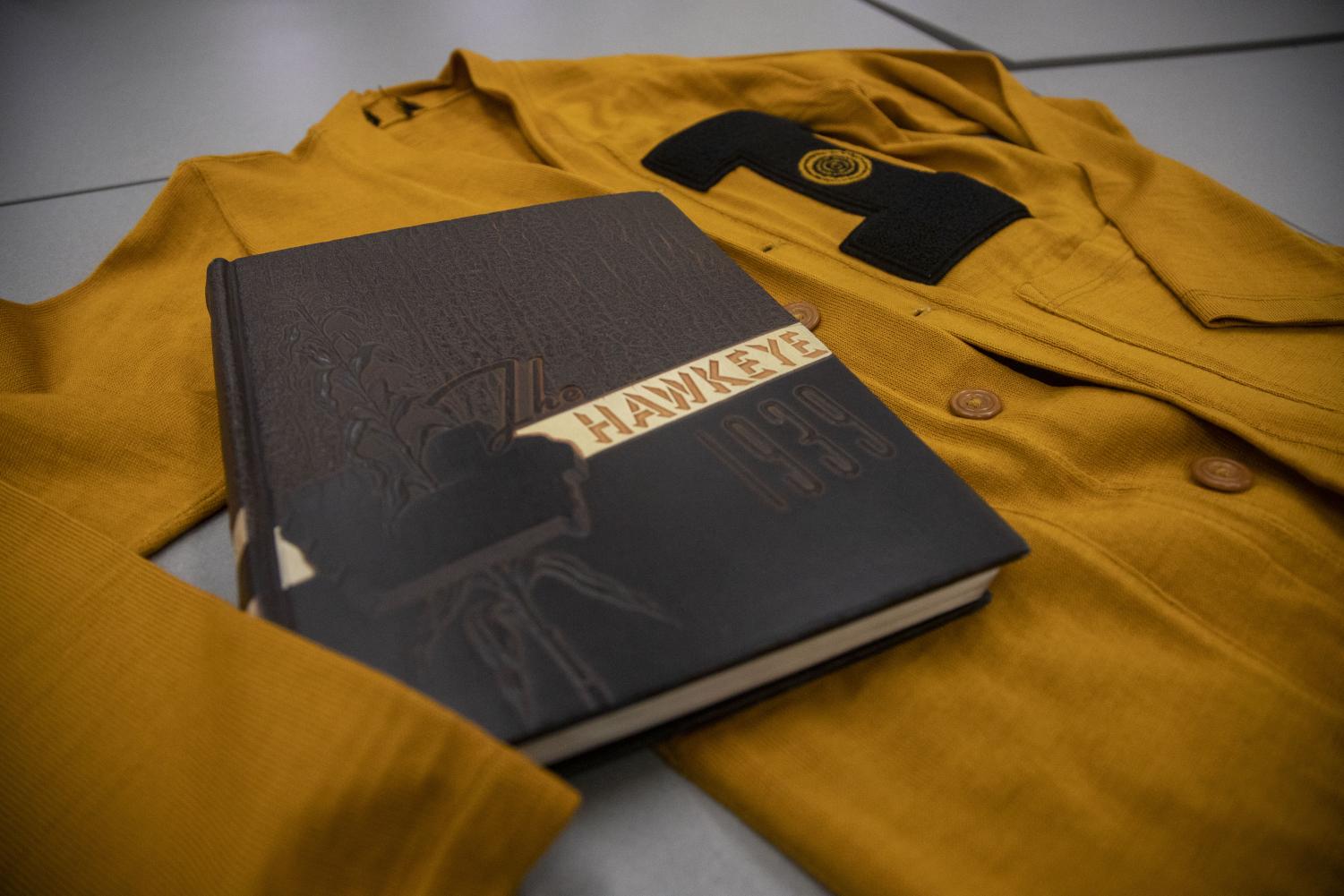

Outside of physical protests, Hawkeyes have put their ideas in print throughout history. At first, literary societies in the 1890s and 1900s helped students challenge ideas, learn how to speak publicly, and gain rhetorical skills, Bennett said.

“They were learning to debate and would read literature to one another,” she said. “It gave students a voice outside of the classroom.”

The men’s Irving Institute and Zetagathian Society, and the women’s Erodelphian and Hesperian Societies, were literary societies that took over the entire third floor of South Hall on the Pentacrest. The groups met weekly for orations, declamations, and debates. In the 1870s and 1880s, the majority of the student population participated in the weekly literary society meetings.

According to James Edward Gilson’s book Changing Student Life Styles at the University of Iowa 1880-1990, the four predominant societies were at their largest before the turn of the 20th century.

These societies died out when Greek life began at the university. Literary societies went from attracting the majority of the university to bringing in less than half of campus to their ranks in a matter of years.

Bettine said students also often found their voices in publishing newsletters for individual communities on campus.

“If a student wanted to write something, there was a place that wanted to publish it,” he said. “The array of types of publications that we have in our collection proves the vastness of the options.”

There were humor magazines and columns, and were newsletters all over the political spectrum.

Bettine said one of his favorite publications was the Gaily Iowan. He said it was the original publication of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Trans, and Allied People’s Union. That union is now the Queer Liberation Front.

“That was a simple newsletter,” he said. “There’s always been a queer publication on campus really since the 1980s forward because we’ve had an LGBTQ student organization since 1971 on campus.”

The Muslim Voice newsletter began in the 1990s. Bettine said the publication started on campus before moving into a community-based publication in town. The publication was an affinity and identity-based publication.

“These newsletters were opportunities for people on and off campus to be connected,” he said.

Newsletters informed students of their opportunities at the UI, Bettine said.

“The happenings around the city and around campus and that’s how people connected,” he said. “Newspaper may be the way people learned where they could go and where there were safe spaces to be. There was a community around it.”

Students have not stopped putting their words to paper and debate, even if literary societies and newsletters have dwindled. In more recent history, publishing opportunities have flourished at the university in a way like never before, wrote UI Magid Center Director Daniel Khalastchi in an email to the DI.

Khalastchi wrote that when he arrived on campus in 2011, a century-and-a-half after the first literary society held court at the UI, there was only one creative publishing opportunity for undergraduate students that was university sanctioned — earthwords: the undergraduate literary review.

“Since that time, we’ve seen tremendous and inspiring growth in this area, and in the Magid Center alone we now work with eight unique publications, with seemingly more being created every year,” he wrote. “This type of growth is only sustainable because of the passion and commitment shown by our undergraduates.”

These days, Khalastchi said students trust their peers with their creative work when it comes to publishing opportunities at the university. Back in the 1860s, students trusted one another to listen to and read their words with care at literary societies’ meetings.

Timeline by Eleanor Hildebrandt/The Daily Iowan

Adding to history in the 2020s

Today, UI students continue to add their voices to the university’s long history of civil unrest. The Pentacrest has again been the scene of various protests just two years into the 2020s.

Bettine said there have been dozens of protest topics in the 21st century, which isn’t typical for barely 20 years.

“The things that we’re seeing in the last 22 years of the Pentacrest and protests that have happened on campus, is that diverse students at a predominately white institution know the power of their voice and their advocacy,” he said. “We’ve seen disability rights protests, protests around cultural centers, and them emerging. We’ve seen a continual push. We can argue that the 21st century affords a lot of people raising their voices here.”

Most recently, the Pentacrest has served as a meeting place for some of the most powerful protests and movements the UI has seen since the Vietnam War.

During the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020, the Pentacrest was used more than any other spot in Iowa City for protesters to gather. Over the two weeks of protests following the killing of George Floyd, local activists returned to the Pentacrest at nearly every event.

Protesters paralleled their 1970s’ counterparts when they took to the highway. Unlike then, however, Black Lives Matter protesters took to the highway multiple times.

University students aren’t the only people using the Old Capitol as a meeting grounds for protests. Iowa City high school students also utilize the Old Capitol’s steps to express their views, including marching out of in-person classes at Iowa City City High to march for reproductive rights in December 2021.

The Sudanese community in Johnson County also staged a demonstration outside Schaffer and MacBride Halls to protest the coup that occurred in Sudan in October 2021.

At the beginning of the fall 2021 semester, hundreds of UI students visited the Pentacrest several times to protest against the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity on campus, and two of its members who were accused of sexual assault in 2020.

As Hawkeyes look back on the 175th anniversary of their university, McCartney said understanding the past — including student and community protests — enables current and future students to know more and understand the UI better.

Bennett said Iowa City and the UI have remained idealistic throughout time because students have voices to share.

“The young people that hope that things can change, there is a coterie of people in this town who would like to see change take place,” she said. “The protesters we saw then, and even now after George Floyd — man, they were radical people in those crowds. They were ready to make their voices heard and they still are.”

Bettine said the Pentacrest continues to serve the Iowa City and the UI communities well, as the stage for dozens of protests where the two populations mix.

“The Pentacrest is where the line between the university and the city blurs,” he said. “The Pentacrest is a landmark in Iowa City and the central hub of campus. But when you’re standing outside and protesting on the Pentacrest, you most likely are standing inward and facing the Capitol. But if that protest turns into a march, you turn around. You walk into and parade down the street. It’s just a very visible place in our community.”