Documented Dreamers: navigating an unclear path to citizenship

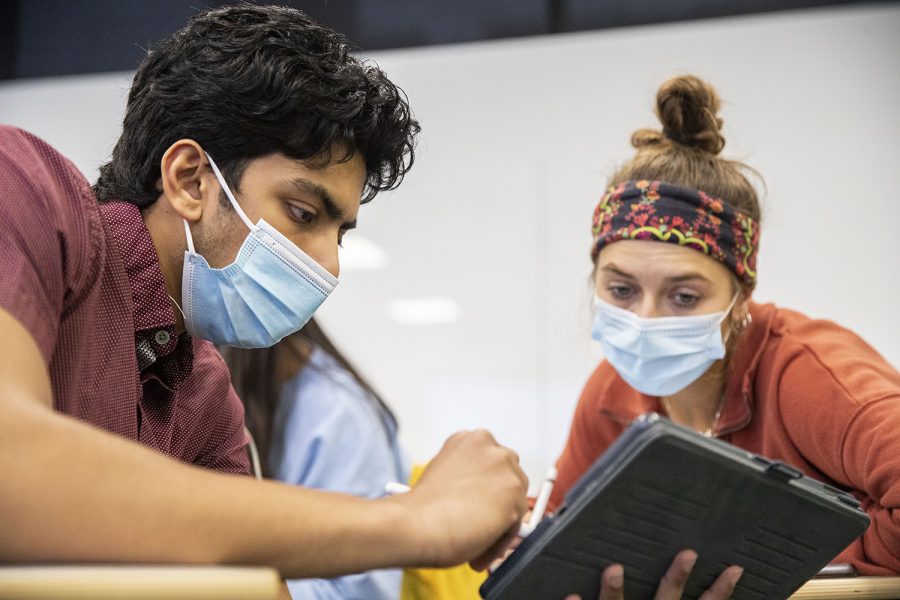

University of Iowa students Kartik Sivakumar and Pareen Mhatre have lived in America for the majority of their lives, yet as documented Dreamers, keeping their legal status in the U.S. has continually meant hoop-jumping, deadline-meeting, and living in uncertainty.

April 17, 2022

Pareen Mhatre and Kartik Sivakumar have spent the majority of their lives in America. They went to high school in America, applied for college in America — but on those applications, they had to apply as international students.

Mhatre and Sivakumar, both University of Iowa students, are “documented Dreamers” — children who have grown up in the U.S. as dependents of their foreign-born parents, who are long-term visa holders in the U.S.

There is no clear path to citizenship for documented Dreamers. At age 21, they are no longer eligible to be dependents on their parents’ visa — a grim milestone known to the group as “aging out” of the system, and one that means facing self-deportation to avoid enduring removal proceedings before a court.

Mhatre has lived in the U.S. since she was four months old, and said that the fact she was treated as an international student didn’t make sense and hurt her.

“Our families pay taxes, our families contribute to the economy” Mhatre said. “But, in that moment when I was applying for colleges, I was being treated as a foreigner, which is something that I’m not.”

Barriers to authorization for work and ineligibility for social security are additional obstacles Dreamers face.

Sivakumar didn’t understand the limitations of his status until he was 15 years old. He had moved from India with his family at 11 years old and grew up in Cedar Rapids.

He couldn’t apply for part-time jobs that many of his friends had in high school because he was ineligible as a dependent on his parents’ work visa.

“My friends started doing that, but I couldn’t,” Sivakumar said. “I’m pretty well-versed in American culture, the language — like everything I know is almost here, but I can’t do some of the most basic things that most citizens or permanent residents can do. So, that was kind of hard to digest

in the beginning.”

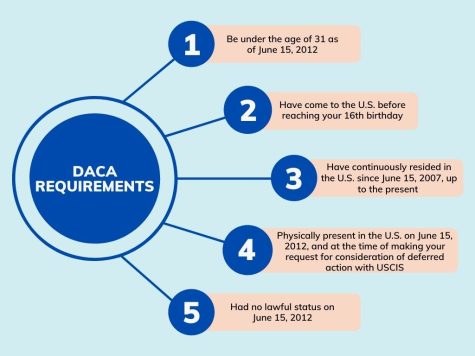

Documented Dreamers were left out of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program (DACA), policy issued in 2012 by former President Barack Obama as a way to protect individuals who were brought into the country as children when their parents entered unlawfully. Documented Dreamers were left out of the program because they have lawful status until they turn 21.

While DACA didn’t grant citizenship, it allowed Dreamers to apply for a driver’s license, social security number, and work permit, while protecting them from deportation.

While DACA didn’t grant citizenship, it allowed Dreamers to apply for a driver’s license, social security number, and work permit, while protecting them from deportation.

Not everyone met the program’s requirements, however, which include being under age 31, having no lawful status, and having a physical presence in the U.S. as of June 15, 2012.

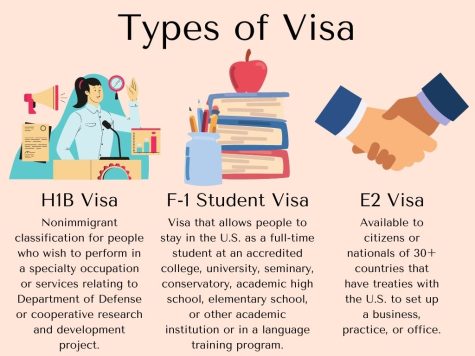

Documented Dreamers don’t qualify for the program because many immigrants come to the U.S. under legal non-immigrant visas such as the H1B or E2.

Mhatre and her family moved to the U.S. from India when she was four months old. Despite living in Iowa City for 20 years as a dependent on her mother’s student visa, Mhatre was legally considered an international student, even when applying to colleges from the place she’d called home all her life.

Applying as an international student meant Mhatre wasn’t allowed to receive federal aid, FAFSA, and most scholarships. She said she’s been lucky enough to pay in-state tuition at the UI by applying for residency at the beginning of each fall semester, but added there are other documented Dreamers who don’t have that luxury.

“They can still go to their state school, but they would be enrolled as an international student, and are forced to pay international tuition and fees,” Mhatre said. “Even if they’ve been living in that state for almost all their lives.”

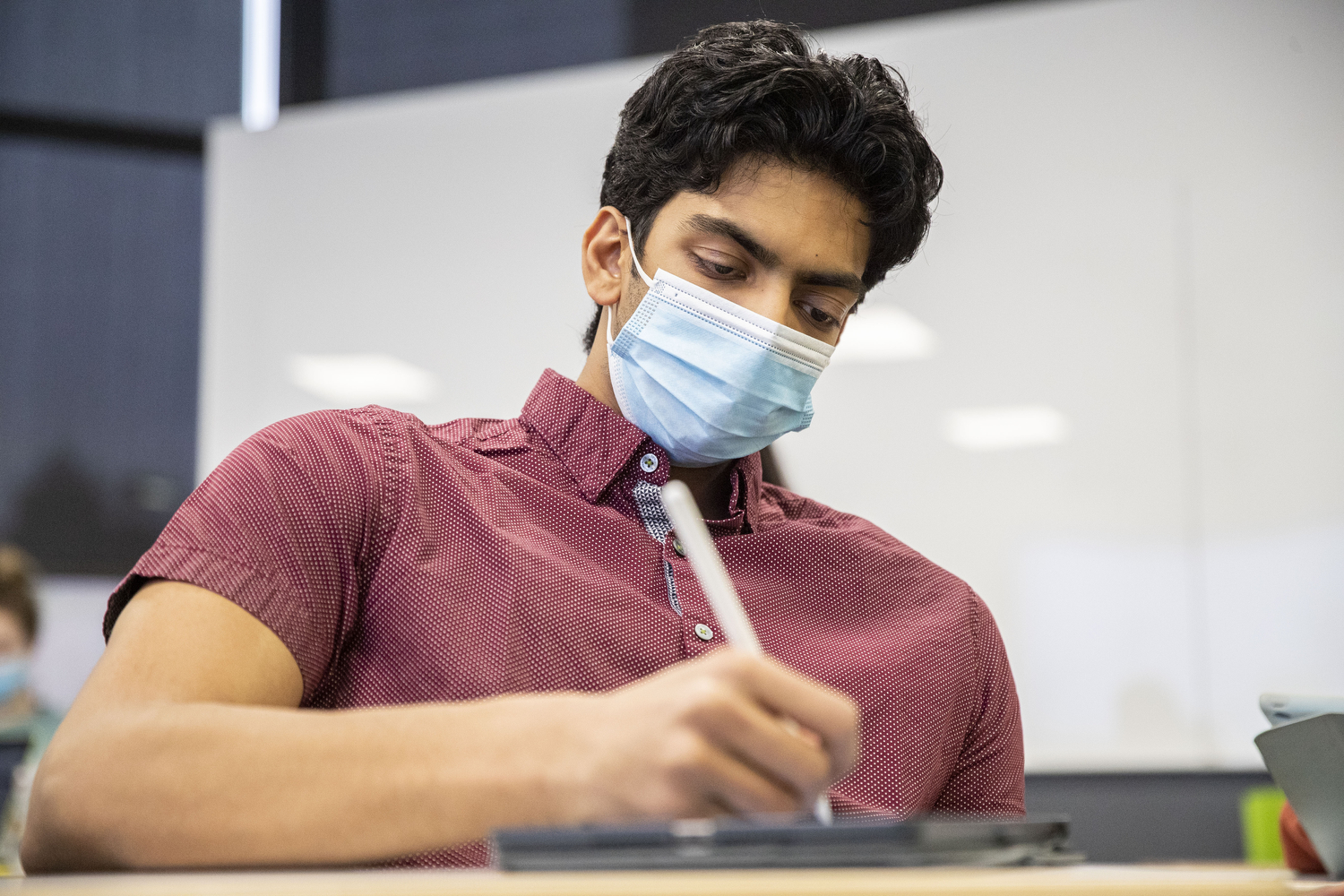

University of Iowa senior studying neurobiology Kartik Sivakumar completes homework during a neurobiology discussion in the Lindquist Center on Tuesday, April 12, 2022.

Aging out

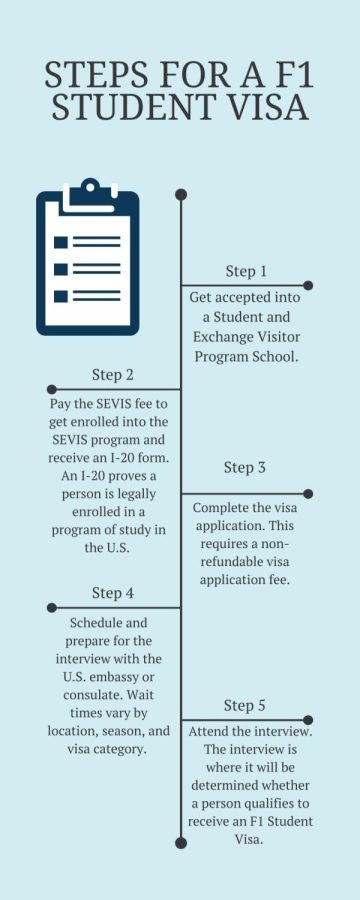

Sivakumar started his application for his F1 student visa at the beginning of his sophomore year of college — approximately one year before he would age out of the system in October 2021.

He didn’t receive an update about his application until a month before his 21st birthday.

Sivakumar was notified that he would receive a date for his Biometrics Appointment, when application identification data such as fingerprints and photos are collected, by Oct. 9.

He was also asked to confirm his mailing address and update it if anything changed in the notice, he said, so he and his family assumed the appointment date would come in the mail.

But as Oct. 9 approached and Sivakumar hadn’t received the date, he decided to call the USCIS services on Oct. 8 to inquire about the appointment.

He was told he missed it.

Sivakumar said he and his family were told the appointment had actually been scheduled for Oct. 4 on their online account, rather than in the mail.

After waiting to hear details about rescheduling the appointment, he was notified months later that his application was denied because he missed the appointment.

By that time, Sivakumar had turned 21, aging out of the system and living in the U.S. without any immigration status for about four months. He said at that point he could either appeal to reopen his case or move back to India to reapply.

He chose the latter because the length of the appealing process was very uncertain, Sivakumar said.

Plus, at that point, he was two months away from possibly being barred from entering the U.S. altogether for three years, according to USCIS admissibility policy.

As the date approached that Sivakumar would depart the U.S., nervousness started to consume his body. On top of the uncertainty of how long he would stay in India, he also had to manage extracurricular responsibilities and make up school work.

“The last couple of weeks before I left were miserable, to be honest,” Sivakumar said. “There was so much going on, I was still busy with school and extracurricular activities. Unfortunately, none of that disappeared.”

Although he knew he would be traveling without his parents, Sivakumar said he did feel excited to stay with his grandparents, who he had only seen a couple of times after moving to the U.S., during family trips to India.

But the weight of the uncertainty lingered until his plane took off, Sivakumar said.

“As soon as I got on the flight to India, I thought to myself, ‘I don’t know when I’m coming back. It could be months, or, maybe a year, I just don’t know,’” Sivakumar said.

When Sivakumar landed in India, he reapplied for his student visa and received a Biometrics Appointment and interview for March 11. He flew out March 10, when he would not only have the Biometrics Appointment, but also receive the decision on his application status.

Before the interview, Sivakumar stood in line to enter the U.S. embassy where he said nervousness started to creep into his body, and his mind swarmed with “horror stories” about people getting rejected in 30 seconds.

Sivakumar expected to be asked one of the three potential interview questions: one about school choice, financial support, and nonimmigrant intent — meaning that the applicant doesn’t intend to stay in the U.S. indefinitely. Sivakumar was worried the officer would be skeptical about his nonimmigrant intent because he spent the past 10 years of his life in the U.S., but the question was never asked during the interview.

“Your job in the interview is to prove to the officer that you will be a nonimmigrant,” Sivakumar said. “They will suspect you are trying to immigrate, and you need to prove to them otherwise.”

Acceptable evidence to prove this includes family and other social relationships, offers of future employment, or property ownership, according

to USCIS.

Administrative processing is when the consular officer, the person who interviews the applicant, feels they need more information to make a decision on the application. It is more common for academic programs that are sensitive to U.S. security such as engineering.

Sivakumar’s application was approved during the interview, and he returned to the U.S. three weeks later, a relief after he expected having to stay in India for

several months.

Although Sivakumar didn’t plan to return to India during the spring semester, he said he was grateful to spend time with and grow closer to his relatives.

“I ate some delicious homemade meals, watched movies with my cousins, helped my grandpa with some errands, sat with my grandma and talked to her about the neighborhood or family gossip or, you know, look at old pictures together of our families, of my other grandpa who recently passed away,” Sivakumar said. “The trip was stressful, but I was grateful for the time with my family.”

Sivakumar described his departure from India as bittersweet. Although he was excited to return to the U.S., he said leaving his family — particularly his grandparents — was difficult.

However, the trip encouraged him to stay in contact more with his family across the ocean.

“Once I went there, I realized how nice it was to have them in my life and I appreciated everything they did for me,” Sivakumar said. “And it’s motivated me to stay in touch with them a lot more. I try to call my grandparents back in India at least once a week now.”

Sivakumar said he felt “pure relief” when he stepped out of the airport back into the U.S.

He decided to surprise his friends with his return by showing up at one of his extracurricular meetings.

“I walked into the meeting, and I waved, ‘Hey, sorry, I’m late.’” Sivakumar said. “They were very surprised, and my close friends got up and ran over to give me a tight hug. It was a nice reunion.”

University of Iowa senior studying biomedical engineering Pareen Mhatre (middle) works on her senior design project with group members Katie Walsh (left) and Ellen O’Connell (right) in the Seamans Center on Friday, April 8, 2022. Mhatre’s group is designing a laryngeal cleft closing device.

Advocating for documented Dreamers

Mhatre aged out of the system in April 2021.

Although she had applied for a student visa 10 months prior in July 2020, Mhatre still had not received a visa by April. While she was no longer eligible to be dependent on her parents’ visa, she had applied for a tourist visa to bridge the gap between the time she aged out and when she received her student visa.

That month, however, she had the opportunity to testify in front of the U.S. Congress as a member of Improve the Dream, a youth-led organization that supports and advocates for young immigrants who have grown up in the U.S. as child dependents of visa holders.

The group’s proposed solution is to “permanently end aging-out and ensure all future action addressing Dreamers allows children who maintained status to qualify if they meet all eligibility criteria, except the requirement to be undocumented,” the group’s website says.

Mhatre joined Improve the Dream in March 2021 after her mom and cousin found the link to join the organization’s slack channel. Mhatre didn’t think Improve the Dream was going to be as big a part of her life, she said, but at the time, she also didn’t realize that there were so many children like her.

Data visualization by Lillian Poulsen/The Daily Iowan

“I filled out this form and the founder contacted me, and he said, ‘Let’s connect, I want to hear your story,’” Mhatre said. “I didn’t realize that there were so many children in this situation. And so that kind of pushed me to help fight for them more.”

Mhatre recalls testifying before Congress as simultaneously “surreal, terrifying, and comforting.” She said she had a large support system from her family, friends, and immigrant community.

“Never did I think our lawmakers would be open to hearing about our issue, or my story,” she said.

After testifying, Mhatre said her email inbox and social media was flooded with messages from people in her exact situation.

Mhatre received her student visa about two months later, and she attributes her testimony, saying she’s a “lucky case.”

Her fortune inspired her to fight for other documented Dreamers and to have more involvement with Improve the Dream. Currently, she serves as the organization’s communications manager.

“There are more than 250,000 of us across this country, and it shouldn’t be that way. It was definitely a learning experience,” Mhatre said. “But also seeing that there were so many people who couldn’t get citizenship drove me to fight harder for them.”

University of Iowa senior studying biomedical engineering Pareen Mhatre works on her senior design project in the Seamans Center on Friday, April 8, 2022. Mhatre’s group is designing a laryngeal cleft closing device.

What happens next?

A student visa doesn’t solve all the problems of documented Dreamers, Mhatre said, who are already behind their peers before they turn 21.

Documented Dreamers aren’t legally allowed to work or even obtain internships that many college students apply for.

Documented Dreamers cannot take advantage of internships like other students, including international students.

“It was hard because I would see all my peers getting to take advantage of these amazing opportunities offered by the industry and medical devices, and they would get to get paid, they would essentially be able to be independent,” Mhatre said “that’s what college is about.”

A student visa is only valid until the individual finishes their degree. On an F1 visa, people are only allowed to stay in the U.S. for up to 60 days after their graduation. Once Mhatre graduates, she will have to apply for a work visa to legally stay in the U.S.

Work visa sponsorship is an expensive process, for which the employer pays. An international employee costs more than a local employee, but because of an enormous number of positions going unfilled, employers still go through with the process.

“When you need sponsorship, the company, in a way, loses money,” Mhatre said. “They have to pay for that process.”

Sivakumar plans to apply for medical school after he graduates. He wants to take a gap year, however, which means he needs to apply for Optional Practical Training for F1 students.

The Optional Practical Training authorization is temporary employment that directly relates to an F1’s major area of study without needing to enroll in classes.

“If I get accepted into med school, I’ll get a new I-20 from them [USCIS Services]” Sivakumar said. “And based on that, I just need that in my visa to be up to date in order to continue my education.”

Jessica Malott, owner and managing partner of Malott Law PLC in Iowa City, which practices primarily in immigration, said she believes that overall immigration policy needs to be improved to make it faster for immigrants,

especially families.

One change Malott believes might make a difference is an independent immigration court. Currently, it is operated under the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review, under the power of the U.S. attorney general.

Immigration courts are civil courts, and the EOIR comprises 58 courts across the country and the Board of Immigration Appeals.

Malott said the current immigration system harms families with problems like visa backlogs and substantial expenses.

“It’s just a lot of time and money, and some families have to be separated through this whole process,” Malott said.

While Mhatre believes that the immigration system needs to change in an ideal world, she said the best strategy right now is to compromise.

“It is tough to have anything passed in the Senate with 60 votes,” Mhatre said. “Which is why, I think, instead of playing with politics— because that affects people’s lives— see what can happen if we try to compromise and pass something that will even help, you know, a smaller portion of people.”

Improve the Dream advocates for the Biden administration to take such action as including documented Dreamers in future administrative and legislative efforts to protect Dreamers. In the past, legislation was introduced in Congress to protect documented Dreamers.

In 2021, Rep. Deborah Ross, D-North Carolina, and Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks, R-Iowa, introduced the America’s CHILDREN Act that would permanently end “aging out” for children of long-time visa holders. A companion bill was also introduced in the senate by Sens. Alex Padilla, D-California and Rand Paul, R-Kentucky.

Mhatre said she hopes future bipartisan legislation will fix a part of the immigration system “that’s been forgotten about for so long.”

“I think the past year itself has given our community a lot of hope. Even the smaller things like getting articles written about our issue, or having the community talk about it,” Mhatre said. “We’ve had a bill introduced in both the House and the Senate with bipartisan support — But I think it’s given me personally a lot of hope, just all these factors.”