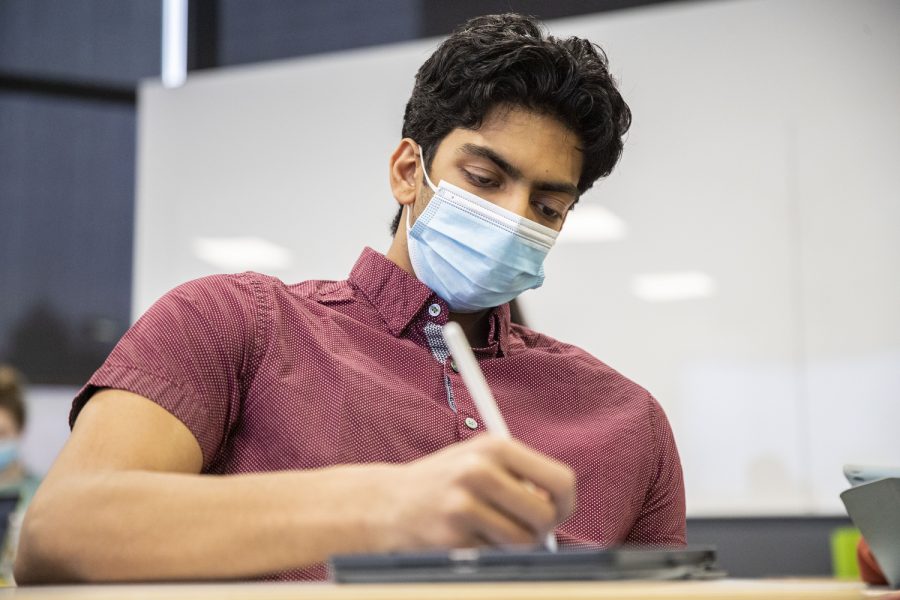

University of Iowa senior studying neurobiology Kartik Sivakumar completes homework during a neurobiology discussion in the Lindquist Center on Tuesday, April 12, 2022.

Aging out

April 17, 2022

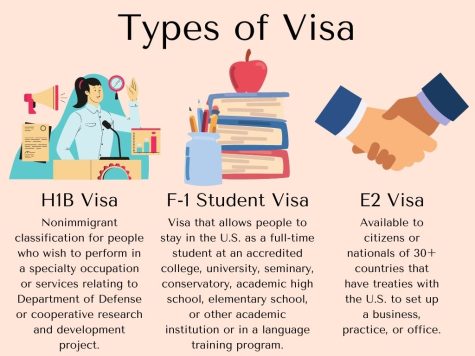

Sivakumar started his application for his F1 student visa at the beginning of his sophomore year of college — approximately one year before he would age out of the system in October 2021.

He didn’t receive an update about his application until a month before his 21st birthday.

Sivakumar was notified that he would receive a date for his Biometrics Appointment, when application identification data such as fingerprints and photos are collected, by Oct. 9.

He was also asked to confirm his mailing address and update it if anything changed in the notice, he said, so he and his family assumed the appointment date would come in the mail.

But as Oct. 9 approached and Sivakumar hadn’t received the date, he decided to call the USCIS services on Oct. 8 to inquire about the appointment.

He was told he missed it.

Sivakumar said he and his family were told the appointment had actually been scheduled for Oct. 4 on their online account, rather than in the mail.

After waiting to hear details about rescheduling the appointment, he was notified months later that his application was denied because he missed the appointment.

By that time, Sivakumar had turned 21, aging out of the system and living in the U.S. without any immigration status for about four months. He said at that point he could either appeal to reopen his case or move back to India to reapply.

He chose the latter because the length of the appealing process was very uncertain, Sivakumar said.

Plus, at that point, he was two months away from possibly being barred from entering the U.S. altogether for three years, according to USCIS admissibility policy.

As the date approached that Sivakumar would depart the U.S., nervousness started to consume his body. On top of the uncertainty of how long he would stay in India, he also had to manage extracurricular responsibilities and make up school work.

“The last couple of weeks before I left were miserable, to be honest,” Sivakumar said. “There was so much going on, I was still busy with school and extracurricular activities. Unfortunately, none of that disappeared.”

Although he knew he would be traveling without his parents, Sivakumar said he did feel excited to stay with his grandparents, who he had only seen a couple of times after moving to the U.S., during family trips to India.

But the weight of the uncertainty lingered until his plane took off, Sivakumar said.

“As soon as I got on the flight to India, I thought to myself, ‘I don’t know when I’m coming back. It could be months, or, maybe a year, I just don’t know,’” Sivakumar said.

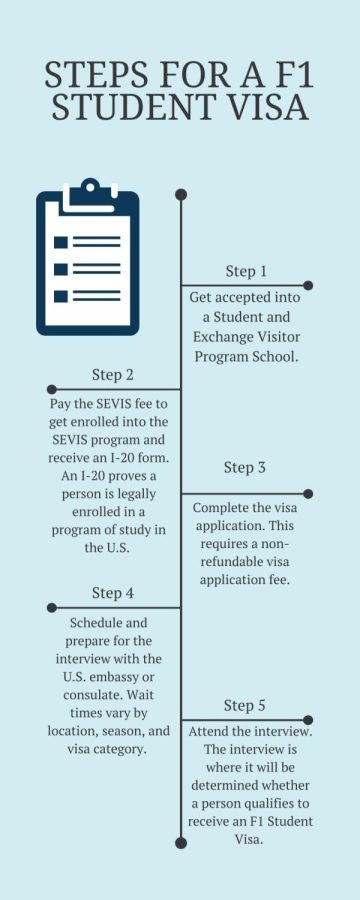

When Sivakumar landed in India, he reapplied for his student visa and received a Biometrics Appointment and interview for March 11. He flew out March 10, when he would not only have the Biometrics Appointment, but also receive the decision on his application status.

Before the interview, Sivakumar stood in line to enter the U.S. embassy where he said nervousness started to creep into his body, and his mind swarmed with “horror stories” about people getting rejected in 30 seconds.

Sivakumar expected to be asked one of the three potential interview questions: one about school choice, financial support, and nonimmigrant intent — meaning that the applicant doesn’t intend to stay in the U.S. indefinitely. Sivakumar was worried the officer would be skeptical about his nonimmigrant intent because he spent the past 10 years of his life in the U.S., but the question was never asked during the interview.

“Your job in the interview is to prove to the officer that you will be a nonimmigrant,” Sivakumar said. “They will suspect you are trying to immigrate, and you need to prove to them otherwise.”

Acceptable evidence to prove this includes family and other social relationships, offers of future employment, or property ownership, according

to USCIS.

Administrative processing is when the consular officer, the person who interviews the applicant, feels they need more information to make a decision on the application. It is more common for academic programs that are sensitive to U.S. security such as engineering.

Sivakumar’s application was approved during the interview, and he returned to the U.S. three weeks later, a relief after he expected having to stay in India for

several months.

Although Sivakumar didn’t plan to return to India during the spring semester, he said he was grateful to spend time with and grow closer to his relatives.

“I ate some delicious homemade meals, watched movies with my cousins, helped my grandpa with some errands, sat with my grandma and talked to her about the neighborhood or family gossip or, you know, look at old pictures together of our families, of my other grandpa who recently passed away,” Sivakumar said. “The trip was stressful, but I was grateful for the time with my family.”

Sivakumar described his departure from India as bittersweet. Although he was excited to return to the U.S., he said leaving his family — particularly his grandparents — was difficult.

However, the trip encouraged him to stay in contact more with his family across the ocean.

“Once I went there, I realized how nice it was to have them in my life and I appreciated everything they did for me,” Sivakumar said. “And it’s motivated me to stay in touch with them a lot more. I try to call my grandparents back in India at least once a week now.”

Sivakumar said he felt “pure relief” when he stepped out of the airport back into the U.S.

He decided to surprise his friends with his return by showing up at one of his extracurricular meetings.

“I walked into the meeting, and I waved, ‘Hey, sorry, I’m late.’” Sivakumar said. “They were very surprised, and my close friends got up and ran over to give me a tight hug. It was a nice reunion.”