UI students express the complications and challenges faced when reporting sexual violence and misconduct through university resources

Students shared their experiences and frustrations that came with reporting incidents of sexual misconduct and violence to the University of Iowa.

November 28, 2021

Editor’s Note: This article makes brief mention of several instances of sexual misconduct and harassment. Because several sources feared retribution, The Daily Iowan granted anonymity to sources who requested it within this article. To protect identities, the DI has assigned several pseudonyms.

Amanda didn’t initially want to report her alleged sexual assault to the University of Iowa.

One year after it happened, however, she filed a formal complaint to the UI Title IX and Gender Equity Unit. When The Daily Iowan asked Amanda to describe what she felt the reporting process was like, she closed her eyes and took a breath. A moment of silence lingered in the air as she selected her next words.

“It felt like a mind game,” she said.

Two out of three sexual assault survivors do not report the assault to police. The reasons vary — some fear retaliation, others believe no one will help.

As Amanda engaged in the reporting process, she, too, felt helpless.

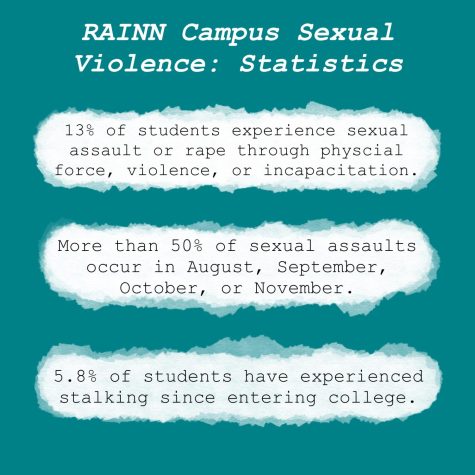

Amanda and four other UI students who spoke to the DI are part of the 13 percent of students who report experiencing sexual assault and violence during their college career in the U.S. Rates across the country of nonconsensual sexual contact increased for both undergraduate men and women from 2015 to 2019 — 1.4 percentage points for men and 3 percentage points for women.

Much of the UI community reeled earlier this year after learning about a sexual assault allegation against two former members of the Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity, commonly known as FIJI, which spurred three consecutive days of protests on campus.

The alleged victim, Makéna Solberg, filed a lawsuit against the members on Oct. 26.

Amanda said she decided to report because the alleged assailant — also a UI student —would call, text, and attempt to get close to her when they were in the same program space after the night of her alleged assault.

As time went on, Amanda said she distanced herself from program events to avoid being in the same space.

After the program director expressed concern that Amanda had become withdrawn from the program events and encouraged her to report the alleged sexual assault, she filed a formal complaint to the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit.

Amanda said she first met with the investigator to tell her side of the alleged assault. After the meeting, she said she received notice that the investigation needed to be postponed for medical reasons cited by the respondent — the label given to the party that the formal complaint is made against.

When the investigation resumed, Amanda said she was brought in for a second interview to talk about the respondent’s version of the story and asked to clarify points that the respondent disagreed with in her story. As time went on, Amanda said she felt like the investigator leaned in favor of the respondent.

Amanda said she brought up in her last meeting with the investigator that none of the provided witnesses who could speak on the night of respondent’s behavior were interviewed. After Amanda asked why witnesses weren’t interviewed, she said the investigator responded, “It sounded like you’re reading from a prepared statement,” and that the investigator didn’t feel like the witnesses could give an accurate account of the night of the alleged assault.

When she was called in by the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit to have the outcome of the investigation, Amanda’s heart dropped. She said the investigator had found no policy violation and decided the case to be a “regretted sexual encounter,” meaning that the investigator believed that she had consented to engage in sexual activity, but regretted it afterward.

“The takeaway from the report was that I was a cocktease that got what was coming toward them,” Amanda said. “‘I played with fire, and I had sex that I didn’t want ultimately and that it’s my fault,’ that’s how the report read.”

Amanda said she not only felt shocked by the outcome, but also by how the investigator interpreted the report. In the report, both Amanda and the respondent said she had said “no” and “stop” during the sexual encounter.

According to the UI definition of consent, “Consent can also be withdrawn once given, as long as the withdrawal is reasonably communicated that, if there is confusion as to whether anyone has consented or continues to consent to sexual activity, the participants must stop the activity until each consents to it.”

Amanda said the report, however, made it seem like the words were used in a flirtatious context and egged the respondent on. In the report, the respondent was never asked if the respondent gave consent, Amanda said.

Per university policy, the exact text of the report was unable to be shared with the DI.

Additionally, in the section about credibility, Amanda said the report stated that both parties were credible. She said that from her perspective, the respondent lied about some details that the investigator didn’t look into. For example, the respondent stated that their roommate was out of town the night of the alleged assault, however, Amanda claimed the respondent didn’t have a roommate at the time.

Meanwhile, she felt “hammered” with questions, including, “Were you asking for it?” and “Are you in the habit of texting men at night?”

After the investigation, Amanda said she regretted buying into what she called “propaganda” that the UI cares about issues such as sexual misconduct and violence.

“This really messed with my head for a long time when I realized not a single person was in my corner,” Amanda said.

“I was so disillusioned after, it’s no wonder why nothing happens and it never gets reported.”

When a UI student reports sexual assault or misconduct to the police, it goes through the law enforcement agency that has jurisdiction for its investigation.

The UI Department of Public Safety investigates any crime that occurs on campus. Hayley Bruce, UI assistant director of media relations, wrote in an email to the DI that if a person reports an assault on campus and calls the Iowa City police, they will likely be directed to UI police to report because UI police have the jurisdiction to investigate the crime.

“Law enforcement agencies do this in order to make sure the victim/survivor does not have to tell their story multiple times as that process can be traumatizing, and we all want to serve our community in a way that is trauma-informed,” Bruce wrote.

At the UI, the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit — formerly known as the Office of Sexual Misconduct and Resource Center — handles investigations for sexual harassment, assault, and misconduct. The office changed its name this year when it merged with the Division of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Before, the unit was under the Division of Student Life.

There are three processes: Process A, Process B, and the Adaptable Resolution, that a formal complaint can follow.

Processes A and B are meant to determine if there has been a UI policy violation, and the adaptable resolution is meant to address harm, UI Title IX coordinator Monique DiCarlo said.

Because the UI receives federal funding, it also has to follow Title IX policy for addressing sexual assault and misconduct.

In higher education institutions, Title IX applies to a variety of areas like recruitment, admissions, and athletics. However, the protocol for sexual assault and harassment policy has caused issues for students who follow through with the reporting process.

When Riley, a UI graduate student, went into their initial meeting with the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit to report alleged sexual harassment, they felt optimistic. Riley ended up leaving the meeting upset and angry because they said they were discouraged from filing a formal complaint of their sexual harassment case.

After encountering uncomfortable experiences that seemed like sexual harassment from a fellow student in their department, Riley said they wanted to voice their concerns.

Interactive by Kelsey Harrell/The Daily Iowan

Riley spoke to a trusted faculty member in the department who put them in contact with the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit. Riley didn’t reach out to the office at first, they said, because they weren’t sure that they wanted to report and didn’t know if the behavior counted as sexual harassment.

A year later, however, Riley contacted the office after learning that the student had made other students in the department uncomfortable.

A meeting was set up between Riley and the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit to figure out if they wanted to file a formal complaint. First, Riley was asked to recount why they wanted to file a formal complaint.

After they explained the interpersonal experience that made them uncomfortable, Riley said that they were “encouraged not to report because the office said there wasn’t enough evidence and didn’t believe a policy violation would be found if filed.”

Riley claimed that they were asked if their decision to pursue an investigation was made to seek revenge against the student. After being asked that question, Riley said they recalled feeling taken aback after hearing that question.

“I just kind of sat there and thought about it for a minute and let the silence hang in the air,” Riley said. “[Wanting to report] wasn’t out of vengeance or anger. I just didn’t want them to do that behavior again.”

Additionally, Riley said they were asked to consider the respondent’s emotions.

“They asked me to consider his feelings and emotions because [the person] was just having a bad day and was mentally unwell and having a difficult time,” Riley said.

DiCarlo said that an alleged behavior has to fall within the policy that is prohibited under section 4.14 of the Sexual Harassment and Sexual Misconduct Operations Manual. If the allegation doesn’t fall under the prohibited behavior, the formal complaint may be dismissed.

“Something can be hurtful, crude, sexist, and fall outside the policy,” DiCarlo said. “It doesn’t mean that it’s OK, but it does mean we would likely have a different way of addressing that behavior separate from a formal complaint.”

In 2019, 521 reports were made to the Title IX and Gender Equity Office for sexual harassment, misconduct, and violence — 158 for sexual assault, 177 for sexual harassment, 105 for dating/domestic violence, 136 for stalking, and 36 for sexual exploitation/intimidation.

Of the 521 reports, the UI opened investigations into 44 of them. Of those, 21 cases were found to include policy violations; 22 were found to possess “no policy violations;” and one ended with a closed case, meaning the respondent withdrew before a finding was issued or the reporting party requested to cease the investigation.

“I almost wish I had gone in expecting less so I wasn’t let down at the end of it,” Riley said. “It’s a huge let down to tell someone all this unsettling stuff that has happened to you and then get asked if you are telling because you’re mad at them and want vengeance.”

While they were aware of the potential problems of sexual misconduct and the reporting process for it on campus, Riley said it was eye-opening to experience it first-hand.

“It is a completely different experience yourself versus just hearing about it,” they said. “I was so disillusioned after, it’s no wonder why nothing happens and it never gets reported.”

“I would’ve liked them to be more realistic about what happens at the end of the process, because I got my hopes up.”

After the initial assessment and if a formal complaint is made, the next step is to determine if a case of sexual misconduct or violence meets Title IX regulations. If it meets the regulations, the case follows Process A, in which the respondent can be expelled or suspended if they are found to be guilty of a policy violation. If not, the case follows Process B.

However, a case that does not meet Title IX regulations still has the ability to follow Process A, if sanctions could still result in suspension or expulsion, according to off-campus behavior policy.

In 2020, the Trump administration and former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos released new changes to Title IX on how schools can handle sexual assault and harassment. The administration policy-makers felt like too many schools inadequately responded to sexual assault and harassment reports and claimed the new policy was meant to protect all students — including those who are falsely accused.

These changes sparked outcry across the nation, with the opposition claiming that Title IX fails to protect the group it is supposed to help: survivors.

The first concern noted by the opposition was the change in the definition of sexual harassment. Under the 2011 definition, sexual harassment was broadly defined as “an unwelcome conduct of sexual nature.” However, the new policy reflected a much narrower definition, indicating such harassment was now defined as “unwelcome conduct that a reasonable person would determine is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it denies a person access to the school’s education program or activity.”

Other concerns included the new requirement of cross-examinations during hearings. In an opinion piece, two University of Michigan professors and a doctoral student called cross-examinations irresponsible because research has proven that it is a poor measure of truth when evaluating cases.

Now, President Joe Biden’s administration is working to dismantle and rewrite the policies the Trump administration and DeVos put in place, with a focus on eliminating barriers to address sexual harassment and encouraging students to come forward.

The Department of Education is planning to release proposed rule changes in May 2022.

Lily, a UI graduate student who engaged in Process A and a subset of it called the Adaptable Resolution Process, called the reporting process draining and frustrating.

When Lily believed she’d experienced stalking from a fellow student, she first went to the Office of the Ombudsperson and was forwarded to the Title IX and Equity Unit.

Lily said she felt overwhelmed by the process during her first meeting with the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit, in which reporting options were discussed. She decided to file a formal complaint that would follow Process A, however, because she felt like it was the only way to resolve the issue.

“I felt like if I wanted anything else to happen, I needed to go through this whole traumatic process,” Lily said. “But I was not really aware of that, and it was a lot in an already difficult time.”

After filing the formal complaint, Lily said she met with the investigator to recount the experience and provide names of people who witnessed the behavior.

Before reaching the live hearing portion of the investigation, Lily said the investigator encouraged her to switch to the Adaptable Resolution process. She said she was told that the process would be faster, less involved than Process A, and give her options for resolutions that she was looking for.

“They said one option would be ‘We could ask this person to receive help,’ and I was like, that sounds wonderful because that’s what [they need], and that’s what I thought would help solve this issue in the future,” Lily said. “But that didn’t end up happening.”

Lily added that she felt pushed into trying out the process.

“It felt a little bit like they didn’t want anything more serious to happen in regards to the reporting process,” Lily said. “It just seemed like they wanted it to go away more quickly.”

DiCarlo said the goal of the Adaptable Resolution Process is not to find if Title IX policy was violated, but instead to address harm. Both parties must agree to the process, and a successful Adaptable Resolution happens when both parties reach a voluntary written agreement. Common resolutions include going through educational programs and mental health counseling, DiCarlo said.

After making the decision to engage in the Adaptable Resolution, Lily said she was contacted by a negotiator from the office to draft a resolution of what harm was caused and what she wanted. Lily, a negotiator, and an advocate from the Rape Victim Advocacy Program, met weekly to work on the resolution, which took about a month to complete.

In the resolution, the respondent was asked to attend mental health programs and to exit extracurricular activities they were in with Lily.

Because both parties must reach a voluntary written agreement, the respondent has the opportunity to negotiate the terms that the complainant lays out. Lily said the respondent initially refused to the terms.

During the negotiation phase, the negotiator meets separately with the respondent and complainant to determine what each party wants. Lily said the negotiator would just report what the respondent would agree or not agree to, and they would have to redraft the resolution until both parties agreed to the terms.

Lily said the negotiation lasted five months before she finally signed the agreement. The resolution determined that the respondent would exit only one of the extracurricular activities, and that they did not agree to enroll in any mental health programs.

In the end, Lily said she felt defeated.

“It just seemed like he got a ton of stuff, and I didn’t get anything out of it, which wasn’t the point,” she said. “The point was for it to be done in a way where he could get help and stuff, but it didn’t end up happening that way.”

Lily said she didn’t have much hope in the process to begin with, and wished that it was more transparent.

“I would have liked more transparency about what was possible under the Adaptable Resolution Process, so instead of promising me we could do this, or ask [the respondent] to do this, none of that happened,” Lily said. “I would’ve liked them to be more realistic about what happens at the end of the process, because I got my hopes up.”

“I didn’t even feel like I was heard.”

During the reporting process, UI undergraduate student Jordan said they didn’t feel like they were being listened to throughout the investigation.

When Jordan met with the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit, the unit laid out the options for filing a formal complaint. Their situation, however, was unique.

At the time of the alleged assault, the complainant and respondent were undergraduate students at the UI. When Jordan reported, the respondent was a graduate student and employee. After months of figuring out where the formal complaint would be investigated, Jordan said it was decided their complaint would be investigated by the Office of Student Accountability.

First, Jordan had an initial meeting with the Title IX coordinator and the investigator. They were asked to recount what happened the night of the alleged assault. Jordan said the basis of the alleged assault was that consent was never given.

Although Jordan said they were drinking, it was not to the point of intoxication or incapacitation. Jordan said, however, the investigator seemed fixated on the idea of them drinking and kept asking questions about whether they were incapacitated or not.

The next meeting Jordan said they were called into was a redo of the initial meeting because there was a new Title IX coordinator on the investigation. Jordan said it was retraumatizing to go through another meeting where they had to describe the alleged assault.

After the second meeting, the investigator met with the witnesses and the respondent. Jordan was then invited into a third meeting, where they were asked more specific questions, including more regarding their alcohol consumption.

Click through to see data related to sexual assault/harassment reports at the University of Iowa.

Data visualization by Molly Milder/The Daily Iowan

After the third meeting, Jordan said they became frustrated over how long the investigation was taking and felt like it was working in opposition to them. They said they felt like they weren’t being listened to because the office kept circling around the idea of alcohol consumption, even though it wasn’t the basis of the complaint.

After the third meeting, Jordan was called back into the unit about two months after the third meeting, and was told there was no policy violation found because the unit couldn’t identify if consent was given.

Jordan said, according to UI policy at the time, the first person to make physical contact must ask for consent, and if they didn’t, it would violate policy. Jordan said the first person that initiated physical contact was the respondent, but they never asked for consent when it was initiated.

“At no point in this fact finding do they include them asking for consent,” Jordan said. “So that means in both my testimony and theirs, there was no consent, and they agreed that there was no consent ever asked for, but they still found no policy violation.”

After consulting with a lawyer about the final determination, Jordan decided to appeal their formal complaint, believing the office didn’t follow its own policy.

While both parties have the opportunity to appeal the outcome of an investigation, DiCarlo said the ability to change the outcome is narrow.

In 2019, 14 out of the 44 resolved investigations were appealed. No decisions or sanctions were overturned or modified.

Jordan’s appeal didn’t change the outcome, and they were told if they wanted to pursue further action, they would have to go through the state Board of Regents. They decided not to go before the regents because they wanted to be done with the process.

Jordan said they felt very angry and upset because the reporting process felt like a traumatizing experience. To this day, they still feel like they haven’t processed it, they said.

“I felt like I gave up a lot of my life to go through this, and I got nothing in return,” Jordan said. “I didn’t even feel like I was heard, so it was difficult.”

Other reporting avenues also present complications

Although there are other ways at the university to pursue complaints against sexual misconduct and harassment besides the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit, there were still complications for Sam, a UI undergraduate student.

When Sam decided to file a complaint against a faculty member for harassment and misconduct, they first went to the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit. Sam said they were told, however, that if they were to pursue a Title IX case, it would most likely be found with no policy violation.

Sam decided not to file a formal complaint and instead decided to go through the UI Ombudsperson. At the first meeting, Sam and the Ombudsperson talked about what Sam wanted, which was for the faculty member to step down from their service appointment. After the first meeting, the Ombudsperson sent an email to the faculty member, who agreed to have a facilitated conversation with Sam.

Before the meeting, Sam asked if they would be able to have a support person. The Ombudsperson told Sam that if they showed up with someone, the faculty member had the right to leave, so Sam decided not to bring someone.

When Sam met the Ombudsperson and faculty member on Zoom, they said they were frustrated by the nature of the meeting. Sam said the faculty member and themself were supposed to address each other by first name, which made them uncomfortable.

Sam said they were also misgendered, despite correcting the faculty member several times and having their pronouns in their name on Zoom.

Sam said the meeting was difficult because they felt like the faculty member was insincere.

The meeting lasted about an hour and a half, and Sam said they didn’t get the outcome they wanted. While they wanted the faculty member to step down from their service position, the faculty member said they were unable to do so and could only step down if found in policy violation.

Instead, the Ombudsperson offered the resolution that if the faculty member needed to contact them, an email would be facilitated with another individual. After pondering the resolution, Sam ultimately felt uncomfortable with this solution and decided to search for other avenues to file a complaint.

Sam said that the process was emotionally taxing, and felt it was very easy to get “lost in the system.” While they felt like individuals wanted to help them, policies made it difficult to give the help that they wanted.

“I feel like there’s very limited benefits for reporting through the university system,” Sam said.

Concerns about reporting sexual assault and violence are also echoed in the U.S. justice system, where prosecutors often hesitate to take on sexual assault cases, particularly where victims knew the accused or if they had consumed alcohol. In eight out of 10 cases, the victim knows the person who sexually assaulted them. Additionally, at least 50 percent of student sexual assaults involve alcohol.

Peter Hansen, an Iowa City trial lawyer told the DI that drinking has not been a major roadblock in his experience with sexual assault cases. Most of his clients deal with situations where the victim and accused know one another.

Hansen said the decision to take on a case depends on individual prosecutors’ standards and oftentimes varies from office to office. The system is also very complex, as victims often confuse the differences between the prosecutor and lawyer.

“Prosecutors don’t represent the complainant, they represent the people of the state of Iowa,” Hansen said. “They aren’t supposed to make a decision based on personal feelings. They’re supposed to go by facts. If they can believe they can prove a case beyond reasonable doubt, they are almost required to file the trial information and pursue it.”

Campus calls for change and resources for survivors

Across the campus community, many members have called and addressed the need for change in the sexual misconduct and reporting process.

Students on campus, such as the organization Cops off Campus, have demanded changes including removing the UI Police Department from the sexual assault reporting process and providing public access to view stages of a sexual assault allegation.

This year, the UI released a new Anti-Violence Plan that outlines around 40 recommendations in prevention, education, and policy changes.

Recommendations included:

- Increasing accessibility and understanding of resources like Title IX support and where to report sexual misconduct

- Create a tiered education program for fraternity and sorority life members and a men’s peer program for fraternity members, and a men’s peer program for fraternity members.

- Using technology and apps to raise awareness of violence and provide resources

In addition to the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit, there are other resources, including confidential ones, to address sexual misconduct and violence that students can contact for assistance.

Resources

Rape Victim Advocacy Program: (319) 335-6000

Iowa Sexual Abuse Hotline: (800) 284-7821

Women’s Resource and Action Center: (319) 335-1486