“I would’ve liked them to be more realistic about what happens at the end of the process, because I got my hopes up.”

November 28, 2021

After the initial assessment and if a formal complaint is made, the next step is to determine if a case of sexual misconduct or violence meets Title IX regulations. If it meets the regulations, the case follows Process A, in which the respondent can be expelled or suspended if they are found to be guilty of a policy violation. If not, the case follows Process B.

However, a case that does not meet Title IX regulations still has the ability to follow Process A, if sanctions could still result in suspension or expulsion, according to off-campus behavior policy.

In 2020, the Trump administration and former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos released new changes to Title IX on how schools can handle sexual assault and harassment. The administration policy-makers felt like too many schools inadequately responded to sexual assault and harassment reports and claimed the new policy was meant to protect all students — including those who are falsely accused.

These changes sparked outcry across the nation, with the opposition claiming that Title IX fails to protect the group it is supposed to help: survivors.

The first concern noted by the opposition was the change in the definition of sexual harassment. Under the 2011 definition, sexual harassment was broadly defined as “an unwelcome conduct of sexual nature.” However, the new policy reflected a much narrower definition, indicating such harassment was now defined as “unwelcome conduct that a reasonable person would determine is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it denies a person access to the school’s education program or activity.”

Other concerns included the new requirement of cross-examinations during hearings. In an opinion piece, two University of Michigan professors and a doctoral student called cross-examinations irresponsible because research has proven that it is a poor measure of truth when evaluating cases.

Now, President Joe Biden’s administration is working to dismantle and rewrite the policies the Trump administration and DeVos put in place, with a focus on eliminating barriers to address sexual harassment and encouraging students to come forward.

The Department of Education is planning to release proposed rule changes in May 2022.

Lily, a UI graduate student who engaged in Process A and a subset of it called the Adaptable Resolution Process, called the reporting process draining and frustrating.

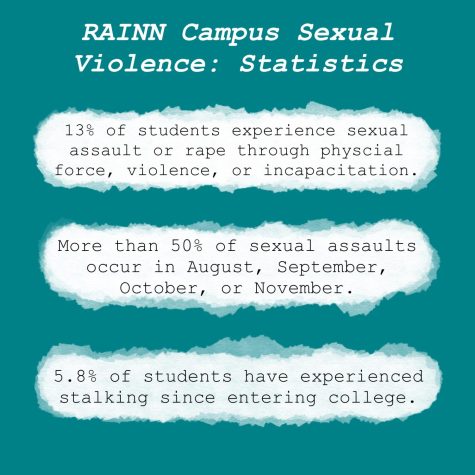

When Lily believed she’d experienced stalking from a fellow student, she first went to the Office of the Ombudsperson and was forwarded to the Title IX and Equity Unit.

Lily said she felt overwhelmed by the process during her first meeting with the Title IX and Gender Equity Unit, in which reporting options were discussed. She decided to file a formal complaint that would follow Process A, however, because she felt like it was the only way to resolve the issue.

“I felt like if I wanted anything else to happen, I needed to go through this whole traumatic process,” Lily said. “But I was not really aware of that, and it was a lot in an already difficult time.”

After filing the formal complaint, Lily said she met with the investigator to recount the experience and provide names of people who witnessed the behavior.

Before reaching the live hearing portion of the investigation, Lily said the investigator encouraged her to switch to the Adaptable Resolution process. She said she was told that the process would be faster, less involved than Process A, and give her options for resolutions that she was looking for.

“They said one option would be ‘We could ask this person to receive help,’ and I was like, that sounds wonderful because that’s what [they need], and that’s what I thought would help solve this issue in the future,” Lily said. “But that didn’t end up happening.”

Lily added that she felt pushed into trying out the process.

“It felt a little bit like they didn’t want anything more serious to happen in regards to the reporting process,” Lily said. “It just seemed like they wanted it to go away more quickly.”

DiCarlo said the goal of the Adaptable Resolution Process is not to find if Title IX policy was violated, but instead to address harm. Both parties must agree to the process, and a successful Adaptable Resolution happens when both parties reach a voluntary written agreement. Common resolutions include going through educational programs and mental health counseling, DiCarlo said.

After making the decision to engage in the Adaptable Resolution, Lily said she was contacted by a negotiator from the office to draft a resolution of what harm was caused and what she wanted. Lily, a negotiator, and an advocate from the Rape Victim Advocacy Program, met weekly to work on the resolution, which took about a month to complete.

In the resolution, the respondent was asked to attend mental health programs and to exit extracurricular activities they were in with Lily.

Because both parties must reach a voluntary written agreement, the respondent has the opportunity to negotiate the terms that the complainant lays out. Lily said the respondent initially refused to the terms.

During the negotiation phase, the negotiator meets separately with the respondent and complainant to determine what each party wants. Lily said the negotiator would just report what the respondent would agree or not agree to, and they would have to redraft the resolution until both parties agreed to the terms.

Lily said the negotiation lasted five months before she finally signed the agreement. The resolution determined that the respondent would exit only one of the extracurricular activities, and that they did not agree to enroll in any mental health programs.

In the end, Lily said she felt defeated.

“It just seemed like he got a ton of stuff, and I didn’t get anything out of it, which wasn’t the point,” she said. “The point was for it to be done in a way where he could get help and stuff, but it didn’t end up happening that way.”

Lily said she didn’t have much hope in the process to begin with, and wished that it was more transparent.

“I would have liked more transparency about what was possible under the Adaptable Resolution Process, so instead of promising me we could do this, or ask [the respondent] to do this, none of that happened,” Lily said. “I would’ve liked them to be more realistic about what happens at the end of the process, because I got my hopes up.”