‘Ben didn’t kill Ben, COVID-19 did’: COVID-19 psychosis impacts Morris, Illinois family

First came COVID-19, then came paranoia. The loss of a loved one in Morris, Illinois highlights the rare subsequent effects of COVID-19, referred to as COVID-19 psychosis.

May 5, 2021

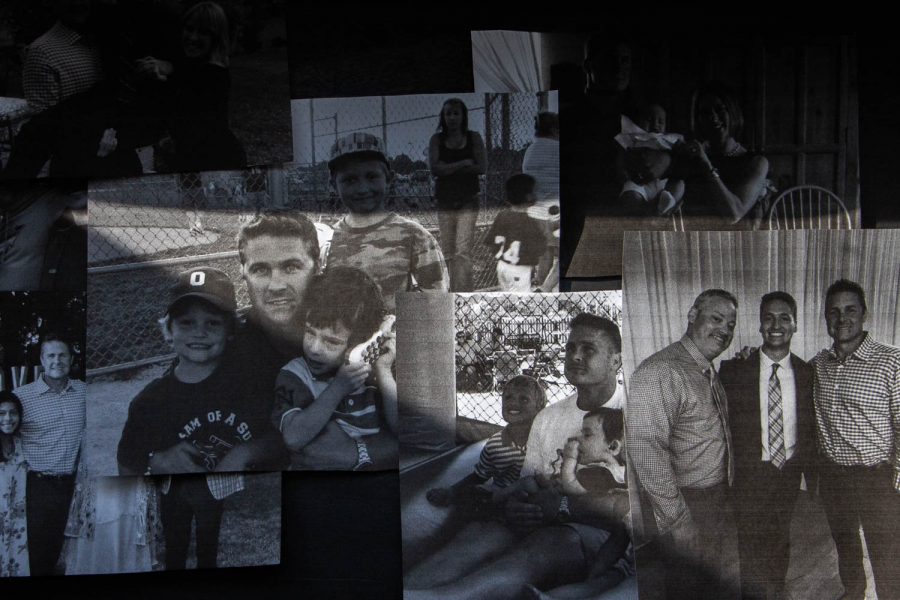

The temperature was approaching 35 degrees as Ben Price drove out to his farm on the last day of February this year. The farm was a happy place for the 48-year-old father and businessman. Just outside his hometown of Morris, Illinois, the wide-open spaces are occupied by a herd of beef cattle and a few donkeys. It was as he and his wife, Jennifer, had always planned.

It wasn’t abnormal for Ben to go to his farm; in fact, it was practically a second home. On this day, however, Ben did not return from it. He took his own life, leaving family and friends grasping for answers.

Two weeks earlier, Ben had tested positive and was hospitalized for COVID-19. Upon his discharge, the normally happy, energetic man’s behavior changed. He became paranoid, scared, and anxious, pacing, and on alert. His family attributes the suicide to a rare phenomenon now known as COVID-19 psychosis, a little studied but very serious reaction to the coronavirus.

The COVID-19 pandemic has become a global source of psychological distress. For those contracting the virus, however, the host immunologic responses may also directly affect the brain and human behavior. According to a case report on COVID-19 induced psychosis, the psychoneurotic effects in victims can produce symptoms including persecutory delusions, auditory hallucinations, suicidal thoughts and behavior, and sleep disturbances.

Psychosis caused by viral infection is not an isolated occurrence. Evidence suggests that as many as 4 percent of people who contract other novel infectious diseases, such as the H1N1 influenza, Ebola, and MERS may develop psychosis.

On Feb. 12, four days after Ben received his first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, someone at his company, The Turf Team, tested positive for COVID-19. Ben went to get tested as well. That test returned a positive result, making him — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — one of more than 31.5 million Americans with a positive COVID-19 test. More than half a million of those who caught the virus have lost their lives.

Like millions of Americans, Ben quarantined. Jennifer, already fully vaccinated, cared for him. But he wasn’t getting better.

On Feb. 18, Ben went to the hospital for an antibody infusion used on coronavirus patients to help their immune system. The next day, he felt worse. Jennifer checked him into the hospital’s COVID-19 ward.

By Sunday, Ben’s heart was in atrial fibrillation, an irregular heart rate that causes poor blood flow, and his oxygen levels were alarmingly low. He was restless — an extroverted, outgoing man, completely isolated without his family in a unit that was overcrowded. Jennifer said his anxiety was high; he needed out. Ben was discharged on Feb. 23. According to Jennifer, he came home a completely different person.

“He started to be very paranoid and panicked; I would just lay there holding his hand, telling him to match my breathing,” Jennifer said. “He was stressing about farming and the fields, but it was February, we couldn’t even do that now. There was nothing we could do to get him to calm down.”

Ben had no history of mental health issues. Like almost all American farmers, his seasons were stressful and sometimes projects got difficult. But Ben had always handled them with a sense of humor and a willingness to learn.

Ben had deep ties to his community. He started The Turf Team in 1995 as a landscaping business and built it into a complex, successful mashup of farming necessities — creating business connections inside and outside the city limits of Morris.

The Turf Team is a commercial array of everything Ben loved. The company is located on top of a small hill in his hometown. The main building is surrounded by red tractors and power equipment to sell. Surrounding it are fields dotted with cows and their calves, donkeys, and the occasional kitten running among them.

Every year when it was time to get the plows dirty and tend to the fields, Ben’s family would be working with him, including his nephew, Max Bolander.

“Ben taught me how to farm, how to run heavy equipment, how to drive, and so much more,” Bolander said. “He was like a second father to me. He wanted to teach me everything and take me everywhere.”

Ben’s ambitions were much different, however, after leaving the hospital. The day before his death, he spent the afternoon pacing throughout the house, checking the windows with each turn. At one point, he stepped out onto the porch and stared into space — his family had to urge him back inside.

Jennifer planned a family night to calm his mind. She made steak for dinner — his favorite. But Ben didn’t eat it. Before testing positive for the virus, Ben loved snuggling on the couch. Saturday night, the family barely got him to sit down. Eventually, he fell asleep on the couch next to Jennifer, their daughter Maya, 14, and son Jett, 17.

Sunday morning, Ben seemed fine. He enjoyed an egg sandwich, fresh coffee, and protein smoothie for breakfast. He swore he felt better, convincingly enough that Jennifer believed it to be the first positive turn in his recovery. No one expected what came next.

The family that dozed off next to him on the couch the night before was left to try to put together the pieces of a puzzle that wasn’t designed to fit.

“Sitting down with people that I am close to and just being able to talk about Ben and his life continues to solidify the feelings that I have about him and the life that he lived — that he was a great man that was stolen from us,” Bolander said.

Like Ben, there are other Americans who have lost their lives to neuropsychiatric symptoms following an infection.

Emily Troyer, a psychiatrist working with the University of California San Diego, released a paper in April 2020 as the coronavirus pandemic began, that reviewed previous literature on the evidence of COVID-19-related neuropsychiatric symptoms in relation to past viral pandemics.

“After a year since the paper was published, we are definitely seeing a lot of neurological and a lot of psychiatric symptoms in COVID-19 patients,” Troyer said.

Her paper indicates that post-viral effects on the immune system could potentially lead to psychiatric symptoms, even if the illness did not directly reach the nervous system.

Despite limited research on COVID-19 psychosis and past pandemics, questions remain for Troyer as to what the exact mechanisms that cause psychosis might be.

“We are seeing syndromes caused by things that wouldn’t have happened had it not been for the viral infection,” Troyer said. “Just because the virus isn’t in the nervous system, doesn’t mean the virus didn’t kick off another cascade of events.”

A possible mechanism of psychosis in COVID-19 patients may be related to the deprivation of one’s senses associated with hospital isolation. Cases of COVID-19 psychosis have also occurred when patients are not hospitalized, however, even in cases of asymptomatic infections.

In Maine, a 64-year-old grandmother, herself and her daughter kept anonymous for the privacy of the family, developed COVID-19 on Feb. 29. She was asymptomatic, healthy, and active in the lives of her three children and their families.

Over the course of her infection, she began obsessively praying over FaceTime with one of her grandchildren, claiming that the prayers were working and healing people. Rapidly, her concern became paranoia. She was constantly worried about spreading the disease and believed that the pandemic was her fault.

The grandmother texted her daughter the morning of March 17 to confirm the pick-up time for her grandchild, and then headed to the beach for her daily walk.

A few hours later, she drowned herself. A teacher for 27 years, she had been an accomplished writer, always putting words together with careful thought. In contrast, she left behind a note of jumbled thoughts, expressing guilt for spreading the virus to a nursing home that she had never visited and at which there had been no coronavirus outbreak. Before contracting COVID-19, just as in Ben’s case, this active, positive, engaged grandmother had no history of any mental health issues.

“She was paranoid about a situation that wasn’t even real, whatsoever,” her daughter told The Daily Iowan. “The person who wrote that letter was not my mother.”

When the Price’s story aired on NBC Chicago, the family in Maine could attach a name to what claimed their matriarch. For the first time, they heard the term “COVID-19 psychosis.”

“It’s clear as day, that’s my mom,” the daughter said when learning of the symptoms.

As for Jennifer, she first learned of COVID-19 psychosis the day of her husband’s death via a phone call from a close friend. Prompted by the phone call, she read three CDC articles on the topic. No one in Morris or in the community believed Ben would have taken his own life. As the pieces of the puzzle came together, Jennifer understood.

“Ben didn’t kill Ben, COVID-19 did,” Jennifer said.

Specifically, the CDC found that in patients with no history of psychiatric disorders, the probability of developing one’s first psychiatric disorder 90 days after contracting COVID-19 was almost 6 percent higher than with other respiratory diseases. Serious neurological effects are rarer, but have been documented.

The evidence suggests, and his family believes, that Ben unknowingly fell into the grasp of psychosis induced by COVID-19. Had they known to watch for the onset of paranoia, they may have been able to intervene. While the risk is low, awareness that the risk existed at all could make a difference for families like the Price’s and their kindred spirits in Maine.

That is why, for Jennifer and the rest of Ben’s family, spreading the word about COVID-19 psychosis is essential. As both a healing mechanism and a calling, raising awareness has become a primary driver for Ben’s survivors.

Jennifer has organized a Change.org campaign, which has over 21,000 signatures, calling for the Biden administration to appoint a neurology expert to investigate post-COVID-19 psychosis further.

“If it can give one person a chance to help another and keep that person in their life, then that is enough for me,” Bolander, Ben’s nephew said. “My loss will continue to leave a hole in me for the rest of my life but, if someone else can be saved, then a little piece of that hole might be filled.”

In the meantime, memories of Ben have filled their lives in different ways.

A few days after Ben died, Bolander was at the farm, feeding cows. The field was muddy, as was often the case in Spring. At the farm, Bolander had never once fallen to the ground. But that day as he handled a bale of hay, he suddenly found himself on his back in the mud. Bolander went to his dad to tell him what happened.

Suddenly, they both laughed, smiling at the sky, mourning the loss of a loved one and anticipating the moment they’d see him again.

“You didn’t fall, Ben knocked you over,” his father said.

For them both, for them all, Ben’s spirit will never lose its fire.