Deaf education in Iowa: a desire for access, communication, and a sense of belonging in school

Deaf and hard of hearing students in Iowa search for a sense of belonging in their hometown school. Sometimes they find that feeling at home, but other times they find it at the Iowa School for the Deaf.

May 4, 2021

Not being able to hear teachers coupled with feelings of isolation from her classmates caused Nichole Jergens to start struggling socially and academically in high school. Her parents, Janet and Matt Jergens, were concerned upon learning their daughter was barely passing classes and showing signs of depression.

Access, communication, community, and a sense of belonging are some of the reasons students like Nichole enroll at the Iowa School for the Deaf.

Being one of the few deaf or hard of hearing children in a classroom can cause feelings of loneliness, but those feelings typically change when these kids are exposed to Iowa’s Deaf community at the School for the Deaf.

The Jergens’ 17-year-old daughter is deaf in one ear. Once she started fifth grade in the Eagle Grove School District, it became clear she wasn’t understanding everything being taught in her classes. Nichole also had expressed she didn’t feel like she fit in with her peers, Janet Jergens said. But switching to the Iowa School for the Deaf wasn’t easy.

Matt Jergens said he felt they had to “jump through a ton of hurdles” in order to get their daughter into the School for the Deaf and at each step they were met with a roadblock.

According to the Iowa School for the Deaf website, students’ “individual education family service plans” (IFSP) or “individualized educational program” (IEP) — the plans that detail what services a child should receive — need to state the placement for a student at the School for the Deaf.

Matt Jergens said the family’s local Area Education Association told them Nichole didn’t need to go to the School for the Deaf, that her grades were fine and she was passing her classes.

Members of their local AEA told the Jergens for months that Nichole couldn’t attend the school, Janet Jergens said. A group of AEA members, school district administrators, and Nichole’s family met to discuss her eligibility to attend the School for the Deaf, taking a tour of the school then voting to determine her future. The vote passed and halfway through her sophomore year of high school, Nichole transferred to her new school in Council Bluffs.

“Nichole wasn’t excited about it at first, she was scared,” Janet Jergens said. But then, “…She loved it. She excelled, I mean she could hear, she could understand, she learned sign language and could understand another way of talking to people.”

With her change in attitude came an improvement in Nichole’s academics; she soon got on the honor roll and is now class president, Matt Jergens said.

They saw her change socially too, Janet Jergens said. Nichole started speaking her mind and wasn’t afraid to ask people to repeat something if she didn’t hear what they said the first time, she said.

The Jergens described Nichole’s transformation after transferring to the School for the Deaf as a butterfly coming out of its cocoon; they saw a complete shift in their daughter’s attitude and emotions.

Deaf and hard of hearing students in Iowa have the option to attend public and private schools across the state — usually referred to as a mainstream setting — or the Iowa School for the Deaf.

The School for the Deaf currently has 92 students enrolled and living on campus, and 16 students enrolled through remote learning. The school was established in 1855 and was originally located in Iowa City, but it was moved to Council Bluffs in 1870 because the city was more accessible by railroad. Students can live in dormitories on campus or if they’re from the area, just attend class during the day. There is no tuition or room and board fees for families. The school serves students from preschool to age 21.

Along with other schools across the state, the School for the Deaf stopped in-person learning at the beginning of the pandemic, Principal Rebecca Gaw said. Wearing masks has also provided some difficulties since the grammatical structure of American Sign Language relies on facial expressions, she said.

The School for the Deaf is a state Board of Regents-governed, state funded institution. The classes at the school are taught in ASL, giving students direct instruction instead of through an interpreter, Gaw said.

According to an Iowa Department of Education report from 2018, 2,775 Iowa residents between birth and age 21 are deaf or hard of hearing.

Unique to the school, roughly 60 to 65 percent of students live on the campus, creating a close-knit community environment with students from all over Iowa and some from Nebraska, she said.

All the employees of the school — teachers, administrators, dorm staff — are fluent in ASL, eliminating the need for an interpreter, Gaw said. There are faculty and staff on campus who are deaf, giving students Deaf role models to look up to, she added.

There are distinctions between someone who is deaf, the condition in which someone can’t hear, and Deaf — someone who identifies as culturally Deaf and participates in the Deaf community.

The class sizes at the School for the Deaf are also small, providing more opportunity for teachers to work closely with students, Gaw said. Elementary class sizes range from two to eight students, middle school ranges from five to 10 students, and high school ranges from five to 12 students depending on the subject, Gaw added.

“So, the students get more attention, not only when [instructors are] teaching core classes just like you find in any other school, like English and math and social studies and science, but they’re also able to provide that support that the kids might need, especially in building language,” Gaw said. “Our students often have gaps because they miss the incidental language that’s happening around them … and they need someone to help fill in information.”

University of Iowa first-year student Emma VandeLune spent her time in elementary school at Cherokee Elementary School in her hometown of Cherokee, Iowa. She worked with a speech pathologist and wore hearing aids to help her hear teachers and classmates. After attending a summer camp at the School for the Deaf — 130 miles away when she was in elementary school — she said she decided she wanted to go to school there.

“One thing that was always so intriguing for me just because I didn’t know sign language that well before going to school there, all these people, these deaf people were communicating, and they were happy and it was just such an interesting turn of perspective for me because I had never been exposed to that,” VandeLune said.

After finishing middle school at the School for the Deaf, VandeLune returned to her hometown high school. She said the School for the Deaf was far from home, contributing to her transfer back to the school district in Cherokee. She also wanted to be challenged more. Sometimes her classmates were farther behind in a subject than she was as students transferred to the school at different times.

“It was a really hard decision, and I thought about it for a while,” VandeLune said. “It sucks because it kind of felt like I was choosing, OK, do I want to be a part of the Deaf community or the hearing community. I think a lot of hearing-impaired individuals have that issue, being stuck between them.”

VandeLune said another reason for her transfer back home was because she wanted to do everything other students could and didn’t want to admit there was something different about her. When she had issues hearing while working at a summer camp, she made the decision to get cochlear implants, which is a controversial topic in the Deaf community. Some members of the Deaf community feel that giving a deaf or hard of hearing child a cochlear implant is an effort to “fix” them.

She said she felt the decision was what was best for her since her whole family is hearing and doesn’t sign, and she plans to go into health care in the future.

“I have to conform to the hearing world, as that’s where I’m going to be working for the rest of my life,” VandeLune said. “It’s one of those things I just kind of came to terms with. So I got my cochlear implant, and it helped me really become more comfortable with my deaf identity.”

Students attending public schools in the state receive instruction in a variety of different ways, Tori Carsrud, Iowa Department of Education program consultant for the deaf/hard of hearing, wrote in an email to The Daily Iowan. Students need to be identified and have an IEP to determine what services they need to receive.

The services provided are unique to each student with an IEP, Carsrud wrote. The teachers for deaf and hard of hearing students around the state know effective teaching strategies and methods to support students and can adapt them to meet the needs of individuals, she wrote.

When considering the best educational option for their child, parents and IEP teams need to work together to figure out what’s best for the student, she wrote.

“Parents and IEP teams have an important role in thinking about the ‘whole’ child and then creatively figure out how to best meet those needs that positively impact the ‘whole’ child,” Carsrud wrote.

Students who are residents of Iowa with hearing loss and who have an IEP and 504 plan — a plan that ensures a child with a disability receives the proper accommodations — are eligible to go to the School for the Deaf, Carsrud wrote.

Gaw said that the children who come to the School for the Deaf often have gaps in their learning, so sometimes they need extra help in a certain subject. The school also has closed captioning on all the televisions and speech and language pathologists on campus to help students, she added.

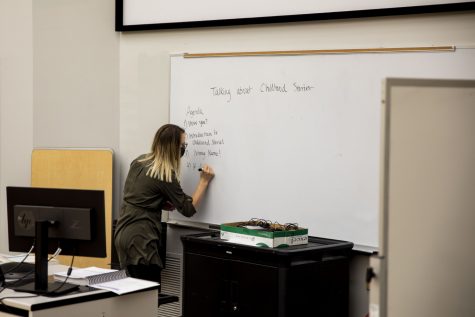

Classes at the school are taught with a mixture of ASL and English, Gaw said. Teachers use written English when using whiteboards and will occasionally use spoken English for students who are oral or use listening skills, she said.

Gretchen Larson, a UI sophomore, went to a mainstream school up until her junior year of high school when she started online schooling. She said that sometimes people don’t understand that she needs some accommodations by looking at her because she’s hard of hearing and her speech is normal.

She said at the UI, her accommodations in classes usually include sitting up front and getting notes from professors. It has been challenging during the pandemic to understand what professors are saying because of mask wearing, Larson said.

Larson said that she sometimes feels isolated because it can be difficult to hear people talking when in public and often people get tired of repeating themselves.

Taking ASL at the UI, Larson said was an eye-opening experience for her.

“It was kind of like, why didn’t I start this earlier? Why wasn’t this available to me at an earlier time?” Larson said. “Because this is such a more effective way of communicating for me and a lot of other people.”

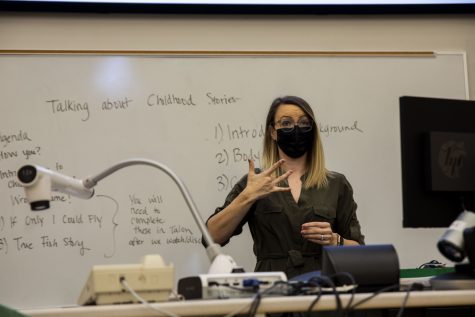

Julia Rabe, an ASL instructor at Kirkwood Community College, grew up with a mix of Deaf culture and hearing culture around her. Her mother is hearing and her father is Deaf, making her a CODA — child of a Deaf adult. She worked as a teacher of the deaf and hard of hearing in a mainstream school before leaving to get her doctorate in educational leadership.

Rabe said she’s conducted research and reading related to language access and language deprivation for deaf students, to work toward improving deaf education programs.

Rabe and others in Iowa were involved with a bill in the Iowa Legislature, HF 604, that aimed to set standards and benchmarks for deaf and hard of hearing students to reach in their learning. This bill, introduced this legislative session, would have also provided a resource to parents to help them understand learning options for their child. The subcommittee on the bill recommended it pass, but it did not make it past a funnel deadline in March.

When working in a mainstream school, Rabe felt like she didn’t have support from administrators and other teachers. She said she ultimately made the decision to leave because she felt the students weren’t being provided the support they needed.

She said since she has a strong signing background, she often functioned as an interpreter in other classrooms, along with her responsibilities as a teacher.

Since her father is Deaf, Rabe said she sees how he doesn’t always have the same access to information that hearing people do, allowing her to understand the struggles of her former students.

“I loved [teaching] right away,” Rabe said. “I think now even teaching higher ed, my heart is still in deaf ed, that’s still where I want to be. But I also know that to affect change, sometimes you have to get out of deaf ed and you have to be on the outside to affect change.”

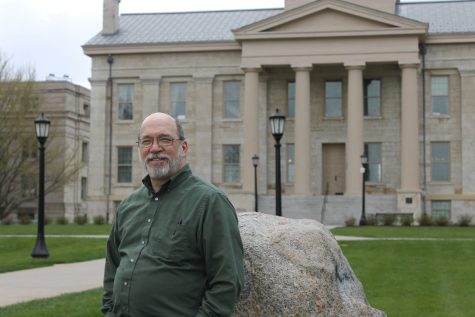

UI ASL instructor Robert Vizzini attended the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf and went to a mainstream school as a child. Vizzini has worked as a Deaf mentor for children in the state and advocated for the Deaf community and deaf education.

“When I moved to Iowa, I realized that people here are kind of behind the times in terms of understanding Deaf people and Deaf culture,” Vizzini signed to an interpreter who verbally translated.

Vizzini has found that he’s had to advocate more for himself in Iowa, he signed.

One thing he observed is that school districts would keep one deaf or hard of hearing student at their local school, instead of sending them to a school or school district with a group of deaf students.

If a student in a mainstream school needs an interpreter, it can be difficult to know for sure if the interpreter is trained well. Vizzini signed that Iowa interpreters aren’t tested before getting their temporary license, making it difficult for him to know if he will get a quality interpreter.

To help make sure students have access to resources they need and parents understand what’s available for their children, the LEAD-K bill — HF 604 — was introduced in the Iowa Legislature.

HF 604 would have helped parents move forward in the process of getting their child’s hearing tested and understanding how they can access language, Vizzini signed. Similar bills have been passed in Georgia, Louisiana, Hawaii, California, South Dakota, and Oregon.

“Parents need to know how to help their kids get an education,” he signed. “Children who are deaf, that doesn’t mean that they’re just going to be behind in everything. It doesn’t mean that they have a limited capability of learning. Deaf kids have the same capability of learning as hearing kids, if they start off in the process and are given access.”

Jennifer Keaton, who is Deaf-blind, attended the Iowa School for the Deaf from kindergarten through 12th grade and felt it helped her figure out her identity and connect with a community.

Her family learned ASL when they found out she was deaf. They gave her access to language and information, something she signed that she is fortunate to have received.

Because she wasn’t dependent on an interpreter to interact with her peers, she connected with people without any sort of barrier, she signed.

“I felt better about who I was and how I identified with the Deaf-blind culture, and I was proud of that identity,” Keaton signed. “I think that in a mainstream situation, people tend to focus on the medical view of a person being deaf, rather than the cultural values. So at the School for the Deaf I just felt that I could be myself and I had more access to learning.”

The big difference between mainstream education and education at a residential school for the deaf is the direct communication to peers and instruction, Iowa School for the Deaf outreach coordinator Tina Caloud signed.

Deaf children miss out on information that hearing children can pick up on from their environment, Caloud signed. If parents can give their child access to language before entering school, they can access anecdotal, environmental information early on.

Caloud encourages parents to visit the School for the Deaf to determine if it’s the right fit for their child. She also encourages hearing parents to meet members of the Deaf community to give their child role models. It’s important to give deaf children access to language beginning when they are an infant, Caloud signed.

“There are many families, not only in Iowa but all over the U.S., that aren’t even aware of the importance of language,” she signed. “So what they’re doing is they’re waiting until later. So by the time their child is four or five years old and goes into school, they don’t really have any language, and they’re not ready for academics.”

Their experience trying to get Nichole into the School for the Deaf inspired Matt Jergens to reach out to state legislators and tell them why it’s important to have a School of the Deaf in Iowa. He is now advocating on behalf of other children to make the admission process easier to understand.

“I’m going to do everything I can, even though our child graduates this year, to see to it that future children don’t have to go through this,” Matt Jergens said. “Because there’s an untold number of kids out there struggling, unnecessarily because they can’t go [to the School for the Deaf].”