Photos by Dick Taffe. Designed by Kate Dolittle

‘Sadly, I feel that we’re all now just ghosts’: 1969 men’s gymnastics Hawkeyes stand alone as national champions

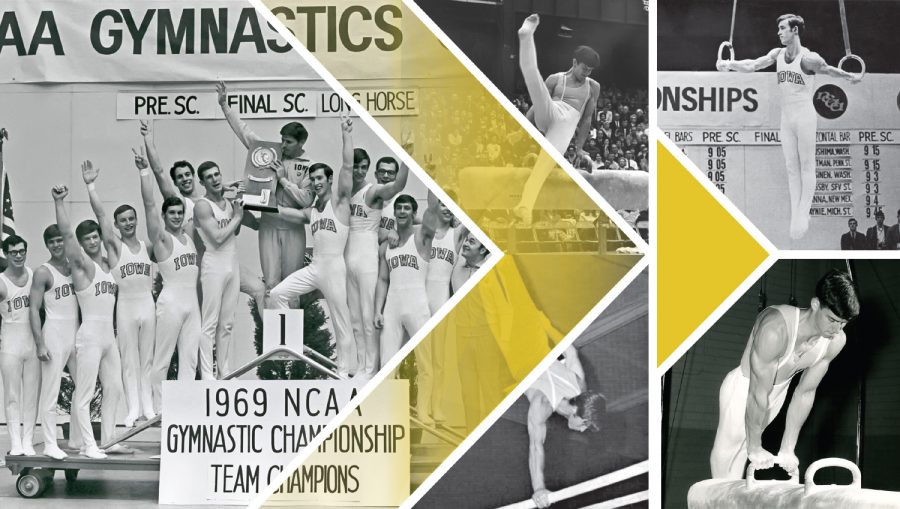

Iowa men's gymnastics ended its final season this month, meaning the 1969 Hawkeyes stand as the program's only national championship team.

April 27, 2021

A display at the University of Iowa’s Athletics Hall of Fame includes a trophy in the national championship teams’ section that carries a special significance.

A gymnast appears at the bottom of the trophy with two hands on the ground and his feet in the air. Lettering to the left of him reads “Gymnastics Champion 1969.” The trophy belongs to the 1969 Iowa men’s gymnastics team, which — before the school became a wrestling powerhouse — won Iowa athletics’ first of 26 NCAA Championships.

The trophy is the Iowa men’s gymnastics program’s only representation in the NCAA title case at the UI. And, ever since the 2020-21 season ended, it always will be.

The Iowa athletics department announced last August that it would discontinue its men’s gymnastics, men’s swimming and diving, and men’s tennis programs at the end of the 2020-21 academic year because of financial troubles brought on by COVID-19. Women’s swimming and diving was also on the chopping block, but it was permanently reinstated in February.

Athletics Director Gary Barta estimated that, with a shortened football season and no fans in attendance at Kinnick Stadium or Carver-Hawkeye Arena this year, along with other losses in revenue, the department is facing a $50-60 million deficit.

The decision to cut men’s gymnastics can’t erase the program’s long history, however.

Men’s gymnastics has been a sanctioned sport at the UI since 1915. Throughout its history, Iowa men’s gymnastics has produced 11 NCAA individual champions, 113 All-Americans, and 93 Big Ten champions.

It’s been 52 years since the program won the NCAA Championships at Edmundson Pavilion in Seattle, Washington, on April 5, 1969, but the story behind those trailblazing Hawkeyes will live on.

A national championship foundation is built

Since Iowa’s high schools didn’t sanction boys’ gymnastics in the early-to-mid ‘60s, most members of the UI men’s gymnastics program came from the Chicago suburbs, including Keith McCanless, who went to Willowbrook High School in Villa Park, Illinois.

McCanless was encouraged to come to Iowa by Neil Schmitt, a gymnast who competed at Iowa from 1966-68 and would later become an unofficial assistant coach for the 1969 team.

Dick Holzaepfel was instrumental in building up what would become a national championship program. Holzaepfel coached the Hawkeyes from 1950-66 and did so again from 1971-80.

Holzaepfel was described by former Hawkeye all-around gymnast Bobby Dickson as being happy, go-lucky. Holzaepfel liked to have fun, Dickson said — he was more of an organizer than coach.

Holzaepfel was an assistant coach at Iowa in 1969. He was inducted into the Iowa Athletics Hall of Fame in 1997.

After the Hawkeyes finished fourth in the Big Ten in 1966, Sam Bailie replaced Holzaepfel as head coach of the program.

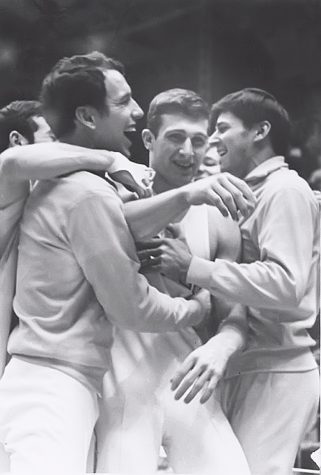

On his first day of coaching at Iowa, Bailie sat the gymnasts on the floor to read his rules. Dickson and Schmitt weren’t having any of it. They looked at each other, got up, and took Bailie by each of his arms. They carried him away, not relinquishing until plopping him down in the showers with a wet thud.

But after that first day, Dickson said, everything went great.

In 1967, Bailie guided his team to a first-place finish in the Big Ten Championships to qualify for the NCAA Championships in Carbondale, Illinois.

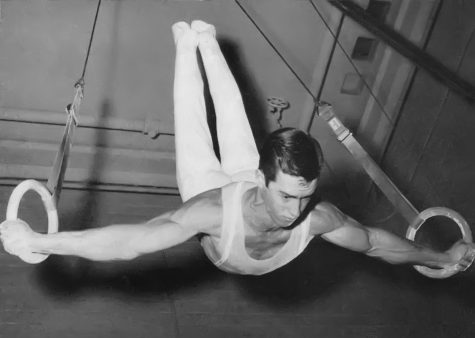

The Hawkeyes finished third at the 1967 NCAA Championships, and McCanless won a national championship on the pommel horse, but Iowa wasn’t satisfied with third.

The Hawkeyes believed setbacks in one event kept them from winning a national championship in 1967.

“If you would have eliminated the trampoline in 1967, we would have won the NCAAs,” McCanless said. “So that was a key issue.”

Iowa finished third again at the 1968 NCAA Championships after finishing in a three-way tie for first at the Big Ten Championships. Iowa claimed the 1968 Big Ten Championships via playoff.

Heading into the 1969 season, McCanless, Dickson, and Don Hatch were all seniors. So, the Hawkeyes’ championship window was closing. Nevertheless, Iowa felt confident that it could win a national title.

Before the 1969 season began, however, Iowa underwent another head coaching change, as Mike Jacobson replaced Bailie in June 1968 after Bailie accepted a position with a sports equipment firm.

Jacobson, who graduated college in 1966, was a gymnast at Penn State.

“Penn State, they weren’t allowed to have any fun,” Dickson said from his residence in the Netherlands. “That’s not a joke. I’ve talked to a lot of Penn State guys since then and they weren’t allowed to go to gymnastics summer camps, they weren’t allowed to go to clinics, they weren’t allowed to have parties and this and that.

“It was just win, win, win, which definitely wasn’t our thing.”

For what Dickson described as a fun-loving group, Jacobson wasn’t the type of coach that fit into the rambunctious team.

There was friction for some time.

Then, an old teammate turned assistant coach went against the discord.

“For the guys younger than me, it was really tumultuous because they had two changes while they were still in school,” Schmitt said. “He wanted to make the team as stable as possible with the talent it had. In his mind, he knew the team would have a chance for another successful year after seeing what it had done the two seasons before.”

Schmitt said the Hawkeyes slowly adjusted to the Jacobson coaching era, accepting his message despite their displeasure with the school’s hiring decision.

During the day, Schmitt worked part-time for the UI and moved inner office guts around. At 2:30 p.m., the moving crew’s truck would drop him off at the Field House where he would work out as if he was on the team, pushing the Hawkeyes to their highest potential.

The 1969 Hawkeyes featured a variety of personalities. For example, Dickson started his acrobatic career when he was young and performed acrobatics at the UI’s annual Dolphin Show, an event that boasted swimmers and gymnasts performing acrobatic stunts.

After winning the 1969 national championship, Dickson took a circuitous path and traveled the world as an acrobat and stuntman performing comedy routines. He retired from acrobatics in 2005 and from comedy in 2020 and now lives in the Netherlands with his wife.

He was inducted into the World Acrobatics Society Hall of Fame as an acrobatic legend and given its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

Dick Taffe was on the 1969 team, and he was also a photographer for The Daily Iowan. Iowa’s journalism and gymnastics programs attracted him to the UI. Even when he couldn’t compete with the team in his freshman year because freshmen couldn’t compete at the time, he traveled with the team to take photographs for the paper. Post-graduation, he would go on to work for United Press International and in public relations, with his last stop being at Boston University, before retiring.

With all these athletes working toward a common goal, the Hawkeyes continued their success from previous seasons in 1969, losing only to Michigan.

The Hawkeyes knew they had a chance to go the NCAA Championships and bring a national title back to Iowa City.

A big change to the format of the NCAA Championship competition would give the Hawkeyes the assist they needed to win a national championship.

RELATED: Iowa men’s gymnastics ends program with two All-Americans

The vault to the top

Iowa did not win the Big Ten Conference Championships in 1969, finishing second to Michigan in Ann Arbor on March 22.

There was a special NCAA Championship qualifier on March 21 of that year, so the Hawkeyes didn’t miss out on their chance at a national championship. From 1948-68, trampoline counted as an event toward the qualifying team score for the NCAA Championships.

A column published by the Michigan Daily shortly after the 1969 Big Ten Championships stated the members of the NCAA Gymnastics Rules Committee benefited from removing trampoline because it would hurt Midwestern schools but help West and East coast schools, saying the elimination was justified because it was “expensive and dangerous.”

The Hawkeyes became a more difficult team to beat with the elimination of trampoline. They beat the Wolverines by .45 points in the qualification meet, even though they won only floor exercise and side horse out of the six events, one of which ended in a tie. Still, the Wolverines won the Big Ten meet the next day.

Dickson scored more points than any Hawkeye in the qualifying, Big Ten, and NCAA meets in 1969, which he only recognized recently because he was focused solely on the team score and his all-around score at the time.

The Hawkeyes advanced to NCAA Championships in Seattle, where they would face seven other teams with a national championship on the line.

Schmitt didn’t go to either the Big Ten Championships or the NCAA Championships. Jacobson bought him a ticket to go to Seattle, but Schmitt suggested that Mike Zepeda go on the trip instead, even though he wouldn’t compete. Zepeda did compete during the regular season as a trampoline specialist but didn’t finish the season because he tore his bicep.

The gymnasts that could compete showed up ready to take the most important meet of the season by storm.

McCanless recalled the Hawkeyes didn’t do as well as they should have in the prelims, but the scores they had qualified for the finals, which included the top three teams. Penn State and Iowa State were the other two teams in the finals with the Hawkeyes.

When it mattered the most, Iowa was the nation’s best. As a team, the Hawkeyes won floor, pommel horse, still rings, and high bar. They defeated the Nittany Lions, 161.175-160.45, and Mike Proctor, who had been shaky in the past, put them over the top with his best routine ever on parallel bars.

McCanless won the individual championship in the pommel horse, becoming the first Hawkeye to take home both an NCAA individual and team championship.

Dickson took third in still rings, fifth in parallel bars, and seventh in all-around. Ken Liehr tied for second in the pommel horse, rounding out the three Hawkeye gymnasts named All-Americans.

“That’s when, for the first time that season, all of us hit our routine,” McCanless said. “There were no breaks, minor or major.”

Back then, the scoring was on a 10-point scale. McCanless said if there was a fall, a gymnast could lose one whole point, but Iowa didn’t have any of that in the finals. Penn State did have some minor breaks.

“It was a great relief,” Taffe said.

The team spent the night in the Emerald City congratulating each other and eating dinner in the Space Needle, enjoying the skyline of the city.

It took them some time to realize they were the first NCAA champions in school history because they won it over the first weekend of spring break. With most of the gymnasts not returning directly back to Iowa City, one even going straight north to Canada, they didn’t get to see that news in the Iowa City Press-Citizen until about a week later. The Daily Iowan didn’t publish an article about the championship until April 8 — three days after it happened.

Decades later and the “Final Flight”

With McCanless, Dickson, and Hatch gone after the 1969 season, Iowa was overpowered by Michigan at the 1970 Big Ten Championships.

Taffe explained that a lot of the Chicago area gymnasts stayed in close touch after the season, and it wasn’t until 2000, when Iowa hosted its last NCAA Men’s Gymnastics Championships, that a number of the gymnasts came back to Iowa City because the program was in contention to become national champions again.

Though the Hawkeyes produced five All-Americans that year, they finished in third place. The highest the program has ever finished nationally since 1969 was second in 1998.

In 2009, the UI finally paid its respects to its first national champions, when the Iowa Magazine published an article headlined “Forgotten Champions.”

McCanless said the story was the catalyst that helped him and his former teammates receive “celebrity” status because, after the article’s publication, they all got championship rings, and four gymnasts — McCanless, Bailie, Schmitt, and Don Hatch — were inducted into the Iowa Athletics Hall of Fame. All of them have been invited back to campus on several occasions.

The most recent such invite was in September 2019 at Kinnick Stadium, for the team’s 50th anniversary. On a bright, warm, and sunny day during a game against Rutgers, the gymnasts were honored in the end zone during a break in the action.

During his nine years as an assistant coach, Schmitt started a private gymnastics club and completed his master’s degree in business administration at the University of Michigan. He then started working for Hewlett-Packard and is now living in Colorado, where he coaches part-time at a local gymnastics club.

Schmitt and Dickson speak via Skype every week, even though they are almost 5,000 miles apart.

Back in Iowa City, 106 years after competing in its first season, the program finished out its final season.

The 2021 men’s gymnastics team that competed under the mantra of the “final flight,” ended its season at the NCAA Championships in Minneapolis April 16-17, with two All-Americans on all-around.

The Hawkeyes placed fifth in the qualifiers April 16, which was two places short of making it to the finals and therefore made the 1969 team the only national champions in program history.

“It has been fun watching this team steadily improve right through their final season,” Taffe wrote in an email to The Daily Iowan. “The spirit to press on when you know it’s the end must have been really hard to maintain. Those of us on the 1969 team are proud to be relics of an earlier time in the very long history of Iowa men’s gymnastics. We’ve admired this final team for their vastly superior skills and technique compared with those in our era. We’re sorry to see this history of continued artistic progress being cut short.

“Sadly, I feel that we’re all now just ghosts.”