Twenty-five years of recovery

April 18, 2020

My mom and several of her coworkers had survived, “at least physically,” she said. Any given morning, there could be 20 people in the DEA office. But the day of the bombing, there were five. It was easy to wonder why, she said.

“We all had survivor’s guilt,” she said. “If you didn’t die, you had survivor’s guilt.”

She and my dad attended eight funerals in seven days. My mom gave eulogies for three of her five co-workers who died. So many of the funerals overlapped, they couldn’t always attend each one.

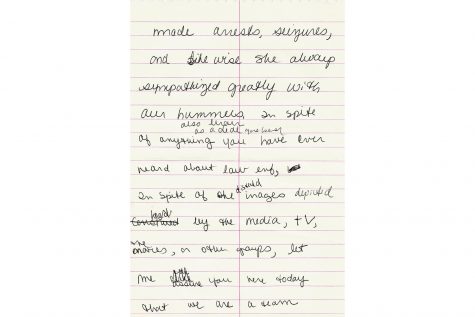

A page from a eulogy for a coworker of former DEA Special Agent Judy Hoke McCarver’s, scribed for a funeral after the bombing is written out on plain piece of notebook paper. McCarver gave eulogies at three of the five funerals for her coworkers who died in the bombing.

“It was sobering,” she said. “I never bought into what people would say, ‘Well, you were saved for a reason.’ I wasn’t saved for a reason. I have a reason for living, but I wasn’t saved for a reason. God didn’t save me and not spare [my friends]. It doesn’t work like that.”

McCarver said she eventually had to stop asking herself “why” the bombing happened the way it did and start asking herself “what.” She had survived — now what?

Bonny agreed, having sustained career-ending injuries in the bombing, undergone several surgeries, and been counseled for post-traumatic stress disorder. The bombing made her appreciate life more, Bonny said. When you see something like that and survive it, she said you try to remember not to take life for granted.

“My body is definitely a constant reminder of what happened,” Bonny said. “Sometimes I get negative, just feeling sorry for myself. But I’ve overcome that and remember that I survived, and my friends didn’t survive, and they didn’t get a chance to raise their children or see their grandchildren. And I always have to remind myself of that.”

Waters said the job wasn’t the same after the bombing. He began drinking, and was suicidal for three years after while still carrying his gun for the DEA. Waters said he wondered why co-workers of his who were “good” had died when he felt he was living a very “bad” life himself.

He decided to leave the DEA and eventually became a criminal-justice professor. Moving on was the best thing for him, Waters said. He’s over 20 years sober now.

Those affected by the bombing are never going to get closure, Waters said. But he has seen people like my mom, who he likened to a sister, accept what happened and reach a good place in regard to her fallen friends.

“You know, the memories of them don’t bring a tear to her eye, they bring a smile to her face,” Waters said. “And I’ve come to be like that too.”