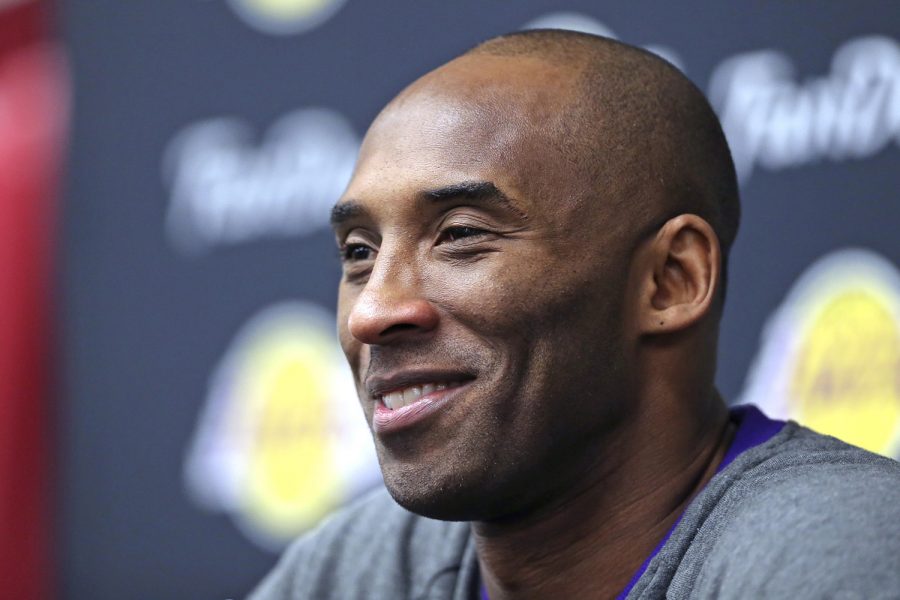

Los Angeles Lakers forward Kobe Bryant, speaks with members of the media, before his team's game against the Chicago Bulls, at the United Center, in Chicago, on Feb. 21, 2016.

Point/Counterpoint: How should we deal with the death of a celebrity?

The death of Kobe Bryant elicited a full range of reactions from fans and media. Two weeks after the star's passing, two DI columnists wrestle with the proper response to this sort of tragedy.

February 9, 2020

Jokes about individuals’ deaths are distasteful and wrong

Novelist Kingsley Amis wrote, “Death has this much to be said for it: You don’t have to get out of bed for it.”

His observation is about the end of life, general enough to be humorous to anyone. However, detailed comments on someone’s death are inflammatory.

This can be seen after the death of NBA superstar Kobe Bryant, who died in a helicopter crash alongside his daughter and seven others on Jan. 26. While the blades still spun, morbid comedian Ari Shaffir tweeted, “Kobe Bryant died 23 years too late today… What a great day!”

Shaffir tried to defend himself later. “They’re just words. They’re jokes for fans.”

Shaffir’s need to explain his remarks rings of Paul Noth’s cartoon depiction of God greeting newcomers at the gates of heaven, “Look if I have to explain the meaning of existence, then it isn’t funny.”

When the joke intrudes on common decency, one should tread carefully, ensuring the taboo being crossed is not diminishing well-being. Sincere or not, Shaffir’s lack of decency broadens the inquiry: How long should our moral timer run before engaging in jokes about the dead?

Of course, the dead cannot take offense, personally or vicariously. But loved ones left behind feel a real emotional impact. One only needs to imagine a former Bryant teammate interrupting a room of damp eyes, “Kobe’s probably coaching God on proper footwork right now.”

How long should our moral timer run before engaging in jokes about the dead?

There is a distinction between jokes about a dead man and jokes about the manner in which a man died. The latter is generally off the table in respect to comedic material. Perhaps the best compromise would be to figure out some guidelines for dark humor. For some, having guidelines at all defeats the purpose of comedy.

For example, a good societal rule concerning posthumous humor could be to wait 24 hours before delivering a punchline. Comedians who post an egregious remark precisely 24 hours after the death of a revered figure ought to be met with the complaint, “You simply waited the required time, and are lacking any sense of common decency.”

I do not wish to conflate bad jokes with sinister ones. Shaffir’s inflammatory comment lacked cleverness, sarcasm, and originality; however, these are traits of a poorly thought out quip, not a malevolent statement. The qualification for malevolence must transcend a naivety of humor.

The celebration of losing a real-life superhero meets the criteria for villainy. Teasing dead celebrities is not the only concern. Many people have emotionally weighted personal accounts of passing relatives and friends. Presumably, those surrounding the deceased loved one have reservations about seeking the humorous aspect.

German communist leader Eugen Leviné lightened the mood before being executed by a firing squad for his rebellion: “We’re all dead men on leave.”

Humor is certainly an antidote, but administer it with caution.

Obsession with celebrities and their deaths has gone too far

Before I start, I don’t want to cast aspersions at specific individuals as I do not know what motivates them. However, a lot of the melodramatic social-media posts and myriad tribute columns mourning NBA star Kobe Bryant’s death seem like empty virtue signals.

It’s so self-righteous. It’s as if they’re telling themselves and others, perhaps subconsciously, “Look at me! I’m a good person because I was among the first to make a profound statement about this celebrity death on Twitter.” And that’s gross.

Some of these social-media users make me wonder if they’ve ever experienced a negative emotion without groveling for attention about it on social media.

The BBC was justifiably flooded with complaints for engaging in too much coverage of Bryant’s death. The endless parade of discussion panels on ESPN were excessive at best, and exploitative at worst.

I watched the beginning of the first Lakers’ game after the tragedy. It featured a round of pre-game festivities to commemorate him. Players wore jerseys with the two numbers Bryant played under, current top Laker LeBron James delivered an emotional speech, and Usher sang a weird rendition of “Amazing Grace.” Call me cynical, but I thought it was over the top.

Technology has enabled Western culture to gradually increase in its idolatry. I find it rather odd that someone can be completely devastated by the passing of an individual they’ve never met. I doubt trends such as #MambaMentality have done anything to comfort Bryant’s grieving family members, who also have not been afforded the proper time and space to cope with their loss.

The endless parade of discussion panels on ESPN were excessive at best, and exploitative at worst.

The fact that some people insist on pretending that Bryant was a flawless person is also a bit strange. He was credibly accused of rape by a 19-year-old woman in 2003, settled a civil lawsuit with her, and issued an apology. Washington Post reporter Felicia Sonmez was briefly suspended from her job after tweeting the link to a Daily Beast story detailing the allegations.

Bryant was a phenomenal athlete who inspired millions of fans to strive for greatness both on and off the court, and my intention is not to detract from that. I was shocked and saddened when I found out about the passing of Bryant, his young daughter, and seven other lives on that helicopter.

Yet, he was only human. No death justifies an entire week of breathless media attention.

The compulsive, posthumous veneration of Bryant is not an anomaly. Deaths of pop stars such as Prince and politicians such as George H.W. Bush were treated in a similarly creepy fashion.

The #RIP brigade of perpetual public mourners don’t seem to fully comprehend that life is fleeting, and death is a natural part of the cycle. No one can escape it, not even celebrities.

America would be a better place if more of its people expressed deeper appreciation for the family, friends, and neighbors who directly improve their lives than superstars on their pedestal who don’t even know them.