The legacy of UI alum George Stout, the father of art conservation

George Stout, a UI alum and former Daily Iowan editor-in-chief, saved priceless art from the Nazis in World War II and became one of the most influential figures in art conservation.

April 17, 2019

I was already in college when I first heard the name “George Stout.”

George Leslie Stout was born in 1897 and went on to become a World War II hero and a pioneer of art conservation. But despite the century of time between our births, the two of us share a few things in common: He was an Iowan who attended the UI. He was the editor-in-chief of The Daily Iowan. And, as it turns out, we are distant cousins.

I did not learn about our common ancestry until my freshman year when I went home for a weekend to Marion, Iowa. My parents had rented the George Clooney-directed film The Monuments Men. It was then my mom told me Clooney’s character in the film was based on George Stout (though they used a different name. Hollywood right?) and his efforts to save and retrieve art stolen by the Nazis during World War II as part of a unit known as “The Monuments Men.” Stout went on to be a leading figure in art conservation until his death in 1978.

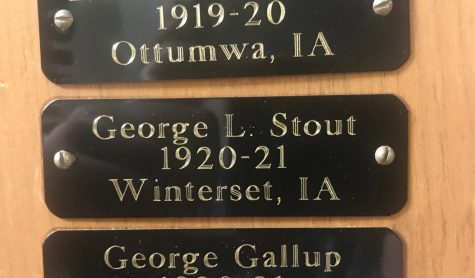

At the time I didn’t think much of it. My college career here at the University of Iowa and at the DI had just begun. I wasn’t that curious about George Stout until one day, in the Adler Journalism Building outside of the DI newsroom, I stood and read the wall of former DI editors.

Their names were displayed in the glass case by the front entrance to the newsroom. I scanned the list, examining the name of those who came before me.

My eyes came across the year 1920-21 and I saw that familiar name once again:

“George L. Stout”

• • •

Iowa City filmmakers Kevin Kelley and Marie Wilkes were drawn to Stout’s story after they finished a documentary about Jackson Pollock’s Mural. The two unveiled their first project under their new nonprofit organization New Mile Media Arts and premièred the film around Iowa. The initial premiere took place in Stout’s birthplace of Winterset. I spent parts of my childhood visiting that town. It’s the county seat of Madison County, Iowa, and the movie setting for The Bridges of Madison County. It’s also the birthplace of John Wayne, but most importantly for me, it’s where my great grandma Stout still lives to this day.

Kelley and Wilkes decided to pursue their documentary on George Stout, the dapper, soft-spoken, and humble art conservator and his career with the Monuments Men and his influence on the science of art conservation. He continued to be an influential figure in the field until his death in 1978.

The documentary, Stout-hearted: George Stout and the Guardians of Art was shown in Iowa City on April 5 at FilmScene. Both the Winterset and Iowa City events were sold out. I attended the Iowa City show with my parents; because of our familial ties with Stout, I was invited to assist with Wilkes, guiding the Stouts on a tour of Iowa City, stopping at spots that were relevant to George Stout’s days on the UI campus.

Filmmakers Marie Wilkes and Kevin Kelley pose for a portrait at MERGE on April 5, 2019.

The filmmakers connected me with members of the Stout family. Some of them, they had talked to for their documentary.

Through conversations with Stout’s relatives, I learned more about George Stout’s personal side. Who he truly was as a father, as a grandfather, as an uncle.

Stout graduated from Winterset High School and studied at Grinnell for two years, leaving to serve in a military-hospital unit during World War I.

Filmmaker Kelley said it was during this time that Stout saw the effects that war had on civilization’s culture.

“He saw the destruction of all the great art,” Kelley said. “This was the first time this kid from Winterset was going to Paris and places and seeing the destruction of art from war, and I think that triggered an appreciation in him, too.”

Stout attended the UI during the early 1920s. Walter A. Jessup, the UI president Jessup Hall is named after, was in his first years of running the campus. Former Hawkeye and the first African-American NFL lineman, Fred “Duke” Slater was dominating Iowa Field and become an All-American and the eponym of Slater Hall.

During his time at the UI, Stout met the woman who became his wife, Margaret Hayes, while taking art classes in Schaeffer Hall. After finishing his undergrad, Stout became an instructor in the Art Department for a couple years before heading to Harvard, which was the start of his career as an art conservator in the Fogg Museum.

Stout and the other Monuments Men went to great lengths to save important pieces of art. Their mission was to retrieve artifacts from Nazis who were stealing art for Adolf Hitler’s envisioned Führermuseum.

This led to adventuring down into European salt mines that were sometimes rigged with booby traps to prevent the Americans or the Russians, who wanted the art for themselves, from taking Hitler’s potential reclaimed artifacts. Many were skeptical about the task at hand, questioning why saving art should be a focus when human lives were being lost.

Stout spoke about how art tells the story of our world, our triumphs, our mistakes. During a speech for the “This I Believe” series, Stout said:

“Although they might wander off, men come back to works like these and back to the way of civilization. I believe they always will. At such tasks they are free from strife, they are calm in the awareness that although the partial of a man’s life is small, the grandeur of men’s growth is infinite. An old saying goes, ‘He who sustains all the calamities of the country can be the king of the world’; and another: ‘The meek shall inherit the Earth.’ This I believe.”

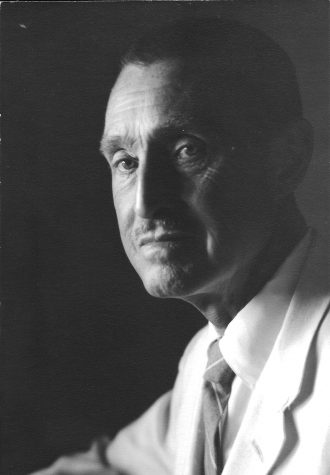

Those who knew Stout described him as humble, hard-working, and well dressed. In his book on the Monuments Men, Robert Edsel refers to Stout as “the dapper George Stout” numerous times. As I talked to relatives of Stout’s from Texas to Maine, they painted the picture of the man behind the monuments.

George Stout’s son, Tom Stout, who currently lives in Maine, said he remembers George as a great man and a great father. George used to take Tom fishing whenever the elder Stout wasn’t working and traveling.

“He would take me fishing whenever he could,” Tom Stout said. “He would do most of the rowing, and I would do most of the fishing.”

Stout’s granddaughters, Leslie Stout Marks, who lives in Texas, and Lauren Stout Parker in Indiana both described their grandfather as dapper as well. The sisters were young when Stout was still alive, and both said though specific memories are hazy, the image of George Stout as a person is still crystal clear.

Leslie Stout Marks, a granddaughter of George Stout, poses for a portrait at MERGE on April 5, 2019.

“He was always dressed, looking dapper as everyone describes him,” Parker said. “He always had that put together look.”

“I remember him being a very dapper, humble, easy-going, laid-back guy,” Marks said. “He was very proper. There were no elbows on the table, very old fashioned, but not in a stuffy, mean way.”

Marks also recalled the times the family were together visiting and her being too young to truly engage in the conversation.

“I wish I would’ve appreciated those conversations and what was being said,” she said. “I remember crawling under the coffee table at everyone’s feet and falling asleep.”

Parker said the most distinctive thing she remembers about her grandfather is his voice.

“He had a smooth, level tone when he talked,” she said. “There weren’t great highs and lows in his expression or his emphasis. Everything was matter of fact and flowed right into the next sentence. He wasn’t one of those people who came down to a kid’s level. He talked to you as if you were an adult.”

There is a scene at the end of Kelley and Wilkes’ documentary that features George Stout’s voice. Parker said this was her favorite part of the film.

“When I heard his voice at the end of the documentary, it was instant tears,” she said. “I just hadn’t heard it in so long. I loved hearing that.”

George Stout’s daughter-in-law, Joanne Rooney Stout married George’s other son, Robert Stout, now deceased. She said George Stout always had an intense interest in anyone who was conversing with him.

“He had blue eyes that were totally penetrating,” she said. “He would ask you questions, and you became his focus. He didn’t want to talk about himself, ever. Unless you were talking about a painting. Then he would talk about that.”

George Stout’s nephew, Richard Stout, described his uncle as very kind, very quiet, and very dry.

“He was always challenging and pushing for instilling knowledge that he had,” he said. “He was a fun guy to be with. There was no direct leadership or pushing to go into any direction. He always wanted to know what I wanted to do and what I was involved in, and then he would start relaying his experience in that area.”

Richard Stout, the nephew of George Stout, stands outside of the old Press-Citizen building on April 6, 2019.

Richard Stout also said his uncle George was the one that taught him how to shave with a straight-edge razor when he was 14. The dapper George Stout is recognizable in black and white photos by his thin, meticulously groomed mustache.

“He would have to correct my angle all the time,” Richard Stout said. “Of course, before he would do that, I’d already put a good cut across my face. I wore a lot of Band-Aids for a while, but he had me keep at it until I got it.”

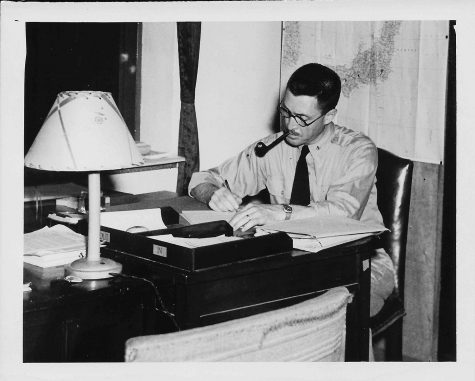

George Stout was also an avid pipe-smoker; Marks and Parker remember their grandfather smoking his pipe often, and Parker said she loved the smell. Richard Stout said his uncle had quite the extensive collection of tobacco pipes.

“In college, I decided that [smoking] might be a nice thing to try, and so he taught me the proper way to smoke a pipe,” Richard Stout said. “It wasn’t too many years later he decided to quit, so he gave me all of his pipes.”

After World War II, George Stout moved to Boston to serve as director of the Worcester Art Museum and later the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The time in Boston included George giving Richard tours of the museum during which George would go through each painting, explaining the restoration work he had done.

“He walked mostly in Boston,” Richard Stout said. “He rarely drove a car. Once, I got a call from my dad, and he said George had been in an accident. I said, ‘From what? He doesn’t drive.’ ”

One day, George was hit by a Salvation Army truck while out walking around Boston and injured his hip.

“We always said after that the Salvation Army was after him,” Richard Stout said and laughed. “He must have needed salvation.”

Richard’s father and George’s brother was Charles H. Stout, the former president of Speidel Newspapers. Charles Stout sold Speidel, which at the time, included the Iowa City Press-Citizen, to Gannett in 1976. Richard Stout said George and Charles were the closest of all of the Stout siblings.

“They spent a lot of time together, always did,” Richard Stout said. “George was the big brother, and my dad just admired him a whole lot. A lot of the rest of the family didn’t at the time, because they didn’t view art as a way to make money. Art wasn’t seen as productive work, and George took a ribbing on that.”

However, those who knew him personally or know about George Stout said there was no one who worked harder than the passionate art conservator who was willing to put his life on the line canvassing all of Europe to retrieve valued pieces of civilization.

Wilkes said George Stout was a meticulous man who combined art and science to pioneer modern methods of preservation. Almost every conservation student around the world still uses the books written by Stout as a primary text when learning how to conserve art.

“There were a lot of people working in art conservation that drove George nuts,” Wilkes said. “He just wanted to get the job done. He had artistic sensibilities but a very scientific mind in terms of he liked order. He liked method. He liked observation and documentation. He knew what he wanted and where he wanted to go.”

Marks said she knew her grandfather was involved in the war but never knew to what extent.

“Those stories just weren’t told,” she said. “It just wasn’t in the nature of George Stout to do that. He was too humble. He was doing what he loved. He wasn’t doing it to be heroic. He just loved art.”

Marks added that she didn’t even know about George Stout’s Monuments Men efforts until Edsell’s book came out. After that, Clooney’s film was made and Marks and Parker attended the première in New York.

“I think we have increased the George Stout knowledge and that part of history so much in just the past few years, and I just want to see that keep going,” Marks said. “I’m shocked it’s not in history books.”

Parker said the exposure that her grandfather has been getting in recent years is humbling.

“We are so proud to get to reveal and get to discover all the accolades he so deservingly is receiving now,” Parker said. “Just to think that some of the great pieces in the art world that wouldn’t be here without George Stout and the Monuments Men.”

Wilkes said George Stout’s humility may be one of the reasons that he hasn’t received recognition until recently.

“George was too busy doing to create his own legend,” she said. “He was just too busy getting things done.”

• • •

The morning after the Iowa City showing, I brought George Stout’s granddaughters, Leslie and Lauren, and nephew Richard to the DI newsroom.

I wanted to show them the editor plaque, the only place on the UI campus that recognizes George.

I pointed to the spot that made my brain light up just a couple years before.

“1920-21: George L. Stout”

I turned to look at Richard.

On his face was one of the biggest smiles I have ever seen.