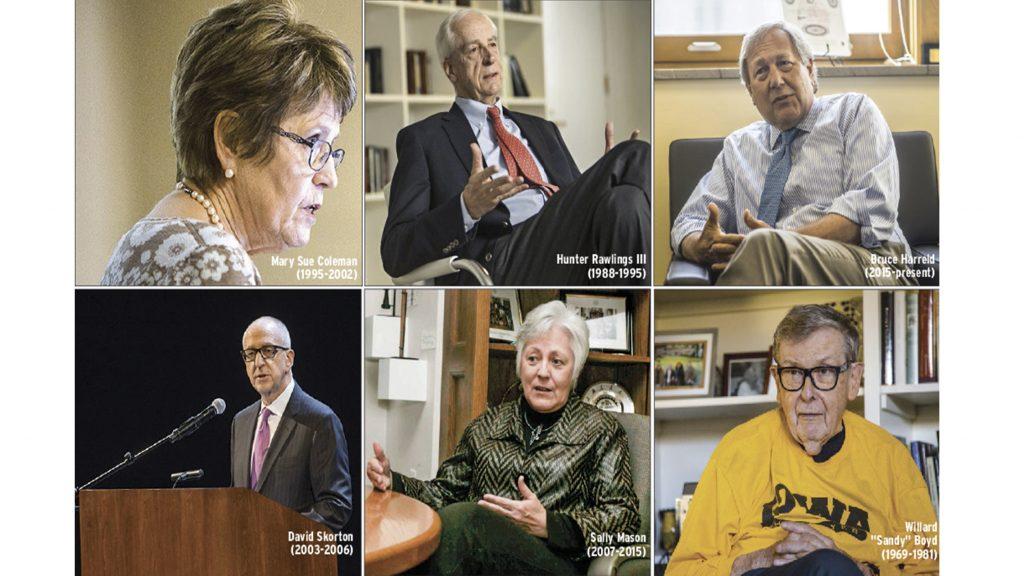

The six living University of Iowa presidents are shown in the present day. Images by The Daily Iowan staff. Hunter Rawlings (top middle) by Robert Barker/Cornell University Photography.

University of Iowa history, told through the head Hawks’ eyes

The six living University of Iowa presidents, past and present, reflect on their tenures at the helm of the institution.

May 7, 2018

Atop the Pentacrest rises a building that has outlasted the University of Iowa’s leaders.

Structures have emerged around the historic Old Capitol and its golden dome — a shining beacon that still stands as the institution’s first building — and remain intact as the people who inhabit them constantly change. The buildings, constructed from limestone, mimic Greek architecture, hinting that the institution’s character and its leaders are to be revered.

There at the heart of campus, the presidents have conducted the university’s work — first in the Old Capitol, now nearby in Jessup Hall. Twenty-one individuals have served at the university’s helm, leading the UI through 171 years as the state’s flagship public higher-education institution.

The Daily Iowan spoke with the six living UI presidents, each having experienced the challenge of leading a top-tier public research university while facing historical obstacles unique to their time periods.

Some were deeply loved and lauded by the community; others found themselves mired in controversy. And for 150 years as the campus’ independent student-run daily newspaper, the DI has covered each president and the events that unfolded during each individual’s tenure.

Willard “Sandy” Boyd (1969–1981)

Age: 91

Positions held since: President of the Field Museum of Natural History (1981-96), Chairman of the American

Association of Universities (1979-80), Interim UI President (2002-03)

Currently: Retired, living in Iowa City

Presidency highlights:

Established the first cultural center amid the Civil Rights Movement

Led the UI through growth in enrollment and added more buildings

Tried to keep the peace during Vietnam War protests

Unrest and tumult characterized the nation at the time and trickled into Sandy Boyd’s presidency — and yet, under his leadership, the UI was set on a path that allowed the institution to grow.

Boyd assumed the university’s top position at the height of the Vietnam War and in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement.

Protests on campus weren’t uncommon, but they remained peaceful. At the end of it all, no one was injured.

On May 4, 1970, members of the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four Kent State University students, some of whom were participating in peaceful protests against the U.S. “secret” bombing of Cambodia.

After that incident a few states away, some students at the UI felt unsafe and wished to return home, while others wanted to finish the classes they had paid for with tuition. Boyd had a multitude of different voices he could have listened to — students, parents, the public — but ultimately, he did what he felt was right. He decided to let students leave if they preferred without penalty, or they could stay to take their final exams.

“What we tried to do is maintain free speech for everybody, not just some people,” Boyd said.

Racial tensions also peaked around Boyd’s presidency. Students made it clear: In the face of domestic threats to their basic rights, they wanted diversity and multiculturalism to be celebrated and supported on campus. This became evident to Boyd one night when a group of African-American students showed up in front of his house, car lights blinding him as he opened the door to invite them inside for a conversation.

After that “strenuous discussion” 50 years ago, Boyd led the charge to establish the Afro House. During his tenure, the UI also added the Latino and Native American Cultural Center, the second of which is now four cultural and resource centers. The centers are situated on the West Campus, with separate buildings that serve under-represented students — the Latinx and Native American, Asian American and Pacific Islander, African-American, and LGBTQ communities — and are still in use today.

He was a young president — only 42 when he took the job. A Minnesota native, Boyd came to the UI in 1954 to teach in the College of Law after a brief time in private practice, eventually moving his way up the administrative ranks to serve as UI president. Now, at 91 years old, Boyd remains an Iowa City resident. The black and gold décor in his room serves as a reflection of his boundless Hawkeye pride.

Boyd focused his presidential tenure on human rights, opening up his office to anyone with concerns they wanted to express and keeping it a place in which people could stop by whenever they pleased.

“I never cut people off,” he said. “No matter how physically tired I was, I would not blow them off. I always paid attention carefully.”

His openness extended to the campus newspaper, and he still considers former reporters lifelong friends today.

It’s the people that matter, he said, at a “wonderful institution” such as the UI.

As his saying goes, “People, not structures, make great universities.”

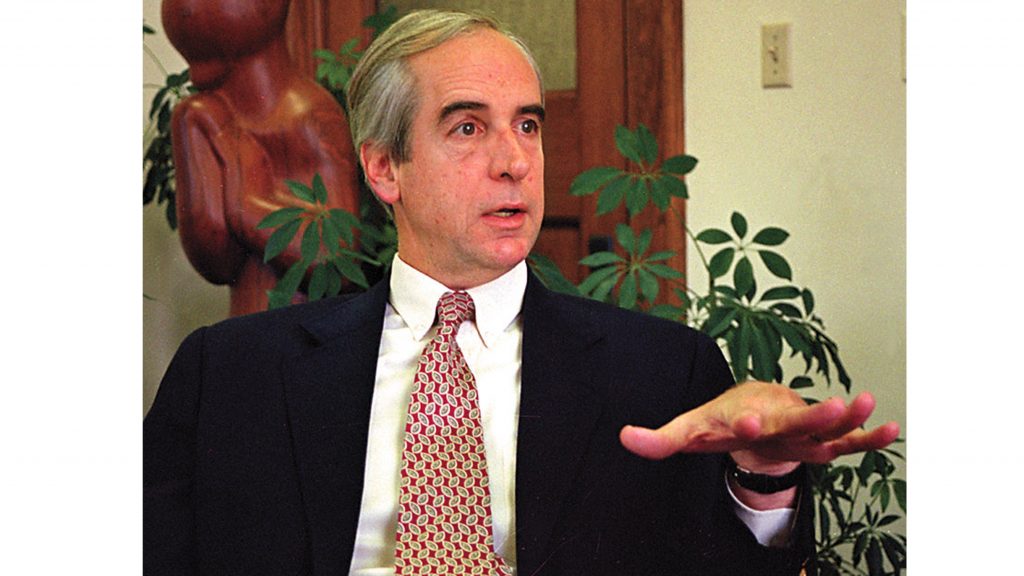

Hunter Rawlings III (1988–1995)

Age: 73

Positions held since: Cornell University President (1995-2003), President of the American Association of Universities

(2011-2016)

Currently: Teaching at George Washington University

Presidency highlights:

The 1991 Gang Lu shooting resulted in six lives lost on the UI campus

Advocated for abolishing freshman eligibility in athletics

Worked with faculty and regents to appease both groups on a policy regarding classroom content

Hunter Rawlings nearly died on the job.

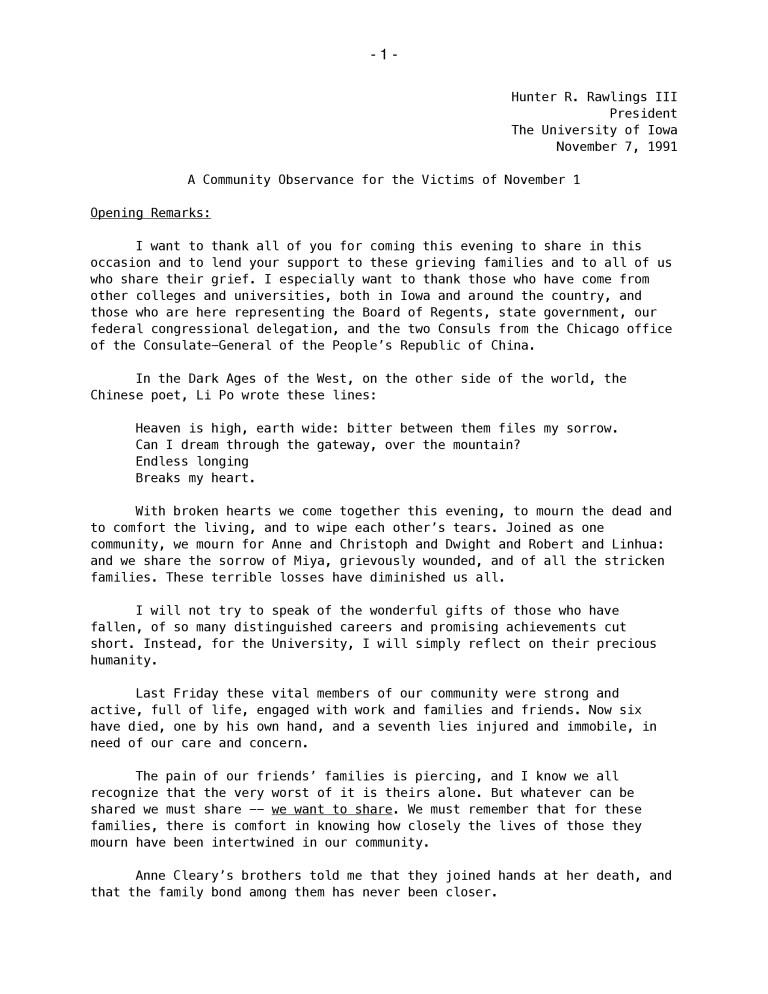

It was Nov. 1, 1991, a day before the Hawkeyes were set to play Ohio State in Columbus. Hunter Rawlings was accompanying the team on its way to Ohio when Gang Lu, a 28-year-old doctoral student, killed five people before shooting himself on the UI campus.

The 17th president was one of Lu’s targets. Had Rawlings been in the President’s Office in Jessup Hall that day rather than hundreds of miles away in Ohio, he might very well have been one of the victims. Two others were shot inside Jessup, one fatally.

“It was a traumatic event for the whole community,” said the 73-year-old Rawlings, who is now retired from serving as Cornell University’s 10th president and teaches at George Washington University.

Even after leading the university through recovery post-tragedy, Rawlings says he misses the campus and the vibrancy of the surrounding community.

A scholar in classics from Virginia, he went on to lead the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Classics Department and later served as the associate vice chancellor for instruction prior to becoming UI president.

From the UI’s strength in the health sciences to its world-renowned Writers’ Workshop, he said, the institution boasts a strong collection of academic programs that make it a great institution.

“I hope I represented what the university stands for, which is academic excellence, and academic freedom, open discussion, high-quality in the arts and humanities as well as the sciences and medicine,” he said.

Especially in his meetings with the DI, Rawlings recalled open discussions and generally positive dialogue. He also remembers criticism but ultimately brushed it off as something to be expected as part of the job.

Rawlings came under fire amid tension between faculty and the state Board of Regents for a policy the governing board imposed on the UI in October 1993 requiring instructors to alert students of sexually explicit course materials, which was interpreted by opponents as a threat to academic freedom.

The policy was formed as a response to complaints from students who were shown a film with homosexual sex acts in class.

Later in January 1994, Rawlings proposed a change to the regents-approved policy, adding the words “and to give students adequate indication of any unusual or unexpected class presentations or materials.” This change broadened the scope from content related to sexual acts to anything a student may find “unusual or unexpected.”

“It’s never much fun,” Rawlings said about being the subject of criticism. “But if you were standing up for something that you think is important, then I think you should do it.”

Mary Sue Coleman (1995–2002)

Age: 74

Positions held since: President of the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor (2002-2014)

Currently: President of the AAU (May 2016-present)

Presidency highlights:

Iowa City adopted an alcohol ordinance as the UI worked on high-risk drinking

The Old Capitol dome caught fire

Initiated a capital campaign to fundraise for the UI

Mary Sue Coleman shattered the UI glass ceiling by becoming the first woman to lead the institution.

Being in command of the university — a hub known for excellence in creative writing and health sciences — was a challenge Coleman found exhilarating.

“In my view, being an effective university president is a difficult job and equally so for women and men,” she told the DI in an email.

Coleman was no stranger to the Heartland. An Iowa native hailing from Cedar Falls, she said taking on the presidency made for an “exciting homecoming,” a return to her family in Iowa.

While she was in a familiar setting geographically, Coleman, then in her 50s, says she found herself in unique scenarios as president and relied on a variety of stakeholders to provide insight on addressing those situations.

She noted monthly meetings with the DI helped her understand the student perspective on issues the campus faced, from tuition increases and impending budget cuts to high-risk alcohol consumption. Coleman lobbied for a city ordinance that passed April 3, 2001, making it easier to enforce the regulation of alcohol service downtown.

“Sometimes I did see that I needed to listen a bit more to concerns from students and the DI was a good vehicle for giving me that insight,” she said.

Colleagues and the broader UI community helped Coleman confront those challenges and others. A fire at the iconic Old Capitol took place during Coleman’s tenure, sparked by welders’ efforts to remove asbestos in the dome. As a symbol of the state, Coleman said, it was important to restore the building to its original glory.

Even with help, Coleman — the 18th president — said, the university president is the face of the university and is responsible for leading the institution through each issue.

“I hope that I encouraged the university to be active in promoting its excellence to the nation and the world,” she said.

The UI presidency wasn’t her last. Immediately following her departure from the UI, Coleman went on to lead the University of Michigan. She succeeded Rawlings again when she became president of the American Association of Universities, a nonprofit organization comprised of national research universities — including the UI — dedicated to advancing society through education, research, and discovery.

Still, Coleman misses those she worked closely with, the warm and welcoming Iowa City community, and the atmosphere of Prairie Lights.

“Every experience forms a trove of information about issues that our institutions face nationally,” she said. “I am deeply grateful for all these experiences of my past.”

David Skorton (2003-2006)

Age: 68

Positions held since: Cornell University president (2006-2015)

Currently: 13th Secretary of the Smithsonian

Presidency highlights:

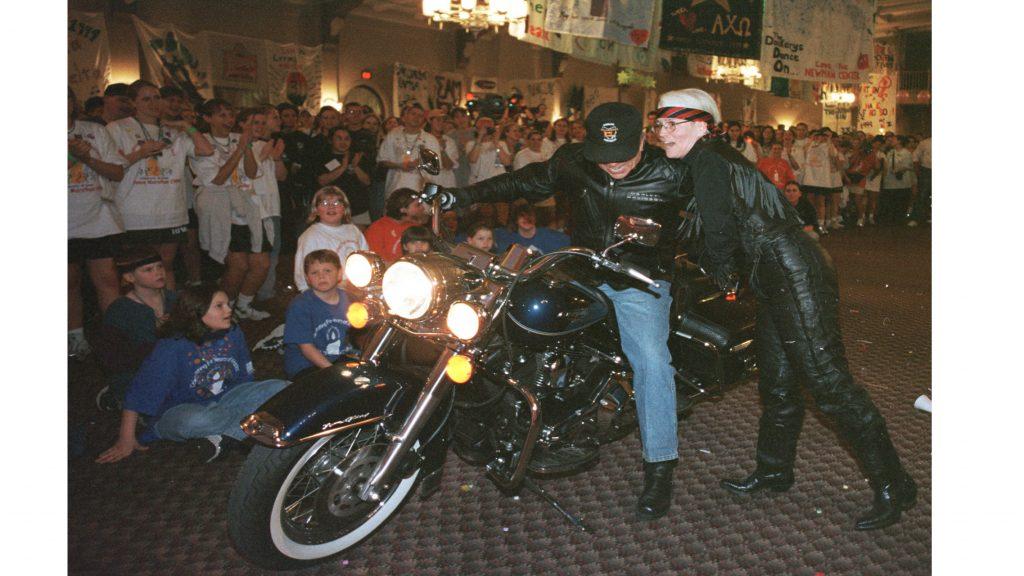

Held the first President’s Block Party

Integrated STEM fields with the arts and humanities

Opened his home to students after the 2006 tornado

He was known as a renaissance man: a faculty member, a physician, an administrator, and a jazz musician. Most of all, though, he was a man who loved the UI, and the community loved him back.

David Skorton wore those many hats throughout his 26 years at the UI before finally serving as the institution’s president. The UI took a chance on Skorton — who at the time was 30 and inexperienced — when François Abboud hired Skorton for his first tenure-track job in the same department.

Prior to his presidential tenure, Skorton also held an appointment in the UI Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and later became the vice president for Research and the vice president for External Relations.

“I have always had a very, very, very warm place in my heart for everything about the University of Iowa,” said Skorton, a Wisconsin native. “I learned a lot and grew a lot as an individual thanks to just the nature of the state of Iowa and the community.”

As the 19th president, Skorton held town halls and opened his home to students in more ways than one. In 2005, he and his wife, Professor Robin Davisson, held the first block party at the President’s Residence during Orientation for first-year students. Once a year, the brick-laden Church Street still fills to the brim with students eager to celebrate new beginnings with the president.

The following year, he opened his home to three UI students, including two DI staffers, after a tornado displaced them from their homes.

“One of the risks of a college presidency is it’s possible to spend a lot of time with every constituent except students,” he said. “To me, the most important constituent that I had always was the student body.”

Reading the DI first thing in the morning is how Skorton said he connected with students and kept up with everything others were doing at the university. As president, all work at the UI was relevant to his position.

“Presidents, I think, need to read student newspapers in their own defense, to make sure they know what students are thinking,” he said.

Originally, retiring somewhere other than the UI wasn’t in the cards for Skorton, who is now the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. It wasn’t until 2006, after a dispute with the regents over an agreement between UI Hospitals & Clinics and Wellmark that Skorton announced he would assume the presidency at Cornell University.

“I spent a lifetime in science and medicine,” he said. “Being at the University of Iowa helped me to understand that the thorniest problems we face as individuals and as a society cannot be solved by science alone.”

Sally Mason (2007-2015)

Age: 67

Currently: AGB search firm consultant

Presidency highlights:

Responded to the 2008 flood aftermath

Helped start the alcohol harm-reduction task force

Launched the six-point plan to combat sexual misconduct

Sally Mason hadn’t been on the job for even a year when disaster struck Iowa City.

The Iowa River flooded some of the city and campus buildings in the floodplain in June 2008. Mason, the “Flood President,” had a lot of rebuilding to do after the flood destroyed buildings such as the old Art Building, Hancher, and Voxman, causing more than $1 billion in damage.

Alongside students and the rest of the university community, Mason filled sandbags beside university buildings and watched help pour in from all over the area.

“We’ll be OK, but we’re not OK at the moment,” she recalled telling her aunt, who called Mason after spotting her on the Weather Channel amid the aftermath.

It’s a statement that seems rather applicable to the road bumps that Mason, now a consultant with the AGB search firm based in Washington, encountered during her presidency.

With the help of city and university officials, Mason set out to shift the party culture to make downtown a safer place for students. The DI, she said, was important in helping her get that message out to campus as, she notes now, the “best source of local news and the most accurate.”

Mason met monthly with the DI, but one February 2014 interview stands out to those familiar with her tenure. She responded to a question regarding reports of sexual assault by noting the difficulty of ending it, saying, “That’s probably not a realistic goal just given human nature …”

After that incident, the DI was only provided one more sit-down interview for the semester, and the UI scheduled media availability sessions for local press in place of a Q&A session in which photographers and videographers were prohibited. Mason said this was a suggestion from one of her senior staff.

“… I recall that when I met with the DI editor that her preference was to go back to my meeting once a month with the DI exclusively,” Mason said. “I was persuaded to return to giving the DI exclusive and regular access because I strongly believe that interviewing the university president is a superb training experience for young, aspiring journalists. This practice continued regularly, and with great success, up until my retirement.”

Although Mason herself said she was a victim of sexual assault, the remarks prompted a swift response from displeased activists. She said she didn’t enjoy being the center of the criticism that ensued and having her comments misconstrued, but she said she appreciated students stepping up to the plate as activists. In response to concerns, Mason launched a six-point plan to combat sexual misconduct.

It was time for the topic of sexual assault on campus to be addressed, she said, and that remains true now with the emergence of the #MeToo movement.

“Much like changing the drinking culture, sometimes you need to have an incident or something happen that becomes a catalyst for a strong movement forward,” she said. “That’s what should happen on college campuses.”

Bruce Harreld (2015-present)

Age: 67

Presidency highlights:

The UI has renewed its focus on multiculturalism and diversity

Opened up the shared-governance process

Aligns spending with the UI’s strategic priorities

On Bruce Harreld’s first day at the UI, he was quite possibly the least popular man on campus.

During the 2015 UI presidential search, five regents met privately with Harreld prior to narrowing down the candidate pool — an opportunity they afforded to no other candidates.

Reports of the meetings had surfaced long before Harreld was on the clock Nov. 2, 2015.

Stacked up against the other finalists — two university provosts and one college president — Harreld was the nontraditional candidate. His résumé lacked the administrative roles the others touted, having held executive roles at IBM, Kraft Foods, and Boston Market, with his experience in higher education being as an adjunct professor at Northwestern and Harvard Universities.

The regents’ secrecy combined with Harreld’s business background and inexperience in higher-education leadership made him the least popular of the final four candidates. The community made that loud and clear with a steady bout of protests prior to — and beyond — his first day.

But Harreld knows who he is. And through strategic planning, he strives to shape the university into an institution that knows its identity, too.

“I think maybe to the extent people have calmed down, they’ve understood who I am, who my family is, what my values are,” he said. “Because I think at the end of the day, it wasn’t so much about business. I think it was the suspicion that my values would be driven primarily by economics and that I was going to run everything through a spreadsheet and … there was this fear that we would become less value-driven.”

Although many of his critics remain, others have opened up to Harreld. Since the first day, several shared governance leaders have told the DI, Harreld has valued shared governance and opened up the decision-making process to campus leaders in ways they hadn’t experienced under past administrations. Harreld has also been praised for the UI’s efforts to embrace multiculturalism and diversity, as the cultural centers have seen increased funding during his tenure.

When he comes into the DI newsroom for regular sit-down interviews, it’s easy to see the man his supporters see. He comments on stories he’s seen in the paper recently, asks how the DI staffers are doing, and encourages reporters (and DI readers) to pass along any ideas they have to make the university better.

On issues such as state funding and the UI’s mental-health resources, Harreld said the DI has provided insight. He said he views the DI as the UI’s paper of record, and with the celebration of the publication’s 150th anniversary, he anticipates its long-term perspective on the university will continue being of value to the students who report on it.

“Somewhere in that long history of time is a perspective — on where we’ve come from, where we’re trying to go,” he said. “I think you invest more in trying to get the story right.”

UI President Bruce Harreld sits down for an interview with The Daily Iowan on Dec. 7, 2017.