Covering a tragedy: the UI’s 1991 shooting

26 years ago, five members of the University of Iowa community were killed in a shooting in Van Allen and Jessup Halls. Local journalists were there to navigate through the chaotic night in a time before mass shootings became a part of modern American society.

November 1, 2017

Οn any average day in Iowa City, hundreds of students stroll along the T. Anne Cleary Walkway, which connects East Side residence halls with the Pentacrest. Yet many of these students would struggle to come up with any information about the person behind the name — Anne Cleary.

Cleary, as well as four others on the UI campus, were shot and killed 26 years ago. The walkway was built as a memorial for the former associate vice president for academic affairs.

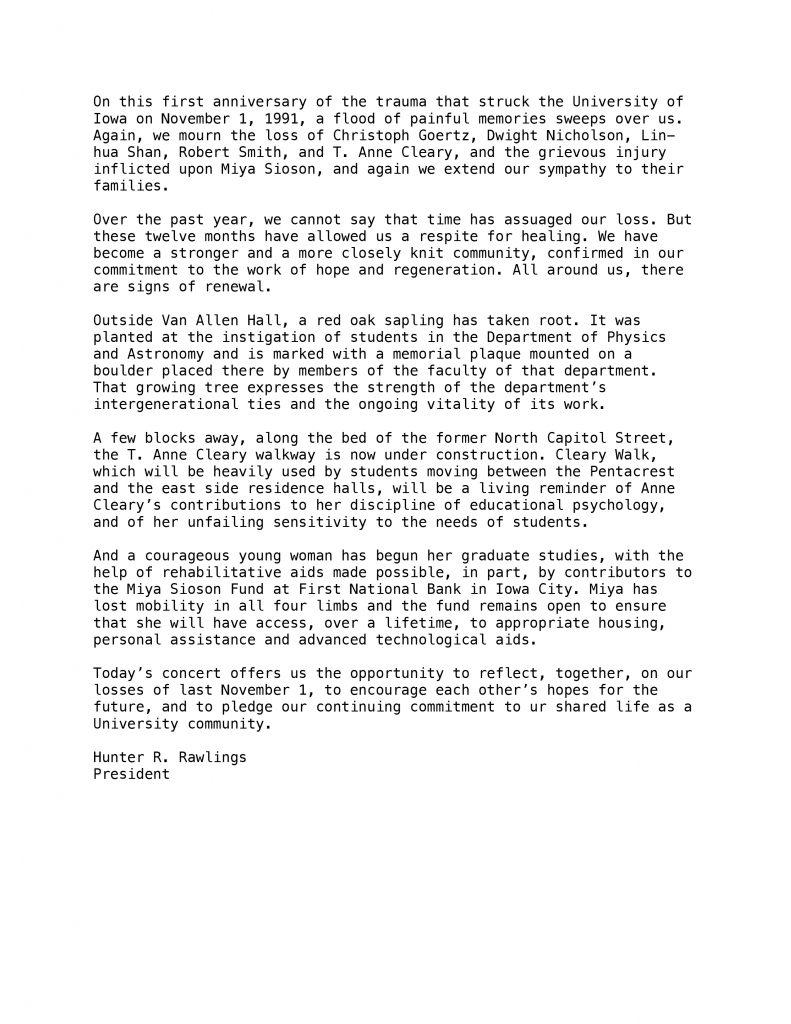

On Nov. 1, 1991, a Chinese former graduate student named Gang Lu shot and killed the five people in two university buildings. Another person, a temp clerk in Cleary’s office, was severely wounded.

Cleary had been assigned to respond to Lu’s grievances about the physics department via month-long email conversations. Lu targeted her and the others who were killed. He had made out a list.

That Friday afternoon was a shocking moment for the victims and families, and national news was watching as Iowa City mourned. School shootings were not a regular part of American society in the early 1990s.

The day also made an indelible impact on the student journalists for The Daily Iowan. Now, 26 years after the shootings, local Iowa City journalists who covered the event as it unfolded recall how chaotic that fall afternoon and evening became.

Then-DI copy editor Annette Schulte is now the associate director of the Jacobson Institute for the UI Tippie College of Business and works in an office in Van Allen. She said every once in a while, the fire alarms go off, and it reminds her of the 1991 shooting.

“The emergency system has this quintessential 1950s movie-narrator voice telling you an emergency has been detected, and honestly, the first time I heard that, it was freaky as hell,” she said. “Then it occurred to me that not everyone would have these thoughts, because 98 percent of students taking classes in this building have no idea what happened here.”

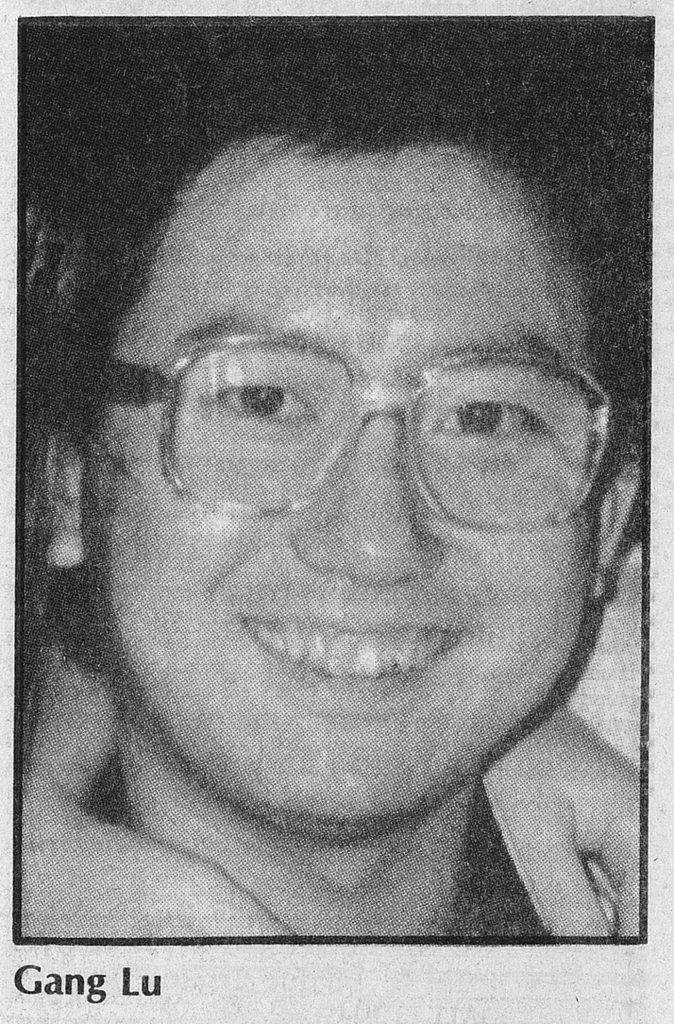

Loren Keller stands outside Van Allen Hall in the spot he stood as a DI reporter in 1991.

Nov. 1, 1991 – What happened

Wind and sleet made for a miserable Friday afternoon in Iowa City on Nov. 1, 1991. As students trudged home in the cold, Loren Keller sat alone in the Daily Iowan newsroom, located in the Communications Center — an often cramped space on the second floor.

Keller was in the newsroom making calls and reporting on a story that would run the next week. Fridays meant an empty newsroom because the DI does not print on weekends — usually.

The clock read somewhere between 3:30 and 4 p.m. when all the desk phones started ringing.

At the time, Keller — now a proposal writer at Pearson — was a junior in his first semester as a reporter.

“I quickly wrapped up my interview and hung up the phone, and it started ringing again immediately, and I picked it up,” Keller recalled. “It was a friend from KRUI and he said, ‘Did you hear? There was a shooting up in Van Allen.’ ”

Van Allen Hall — a towering building perched on the northern end of campus between Seashore Hall and Dubuque Street. The building was named after one of UI’s greatest scientists and scholars, James Van Allen, who was sitting in his top-floor office when the shots of Lu’s gun rang out.

The sound of the shots would make Van Allen Hall synonymous with the most devastating event to shake the UI campus.

Gang Lu first shot Christoph K. Goertz, a professor of physics/astronomy whose time at Iowa was marked by rapid advances in space physics.

He also shot Associate Professor Robert A. Smith and post-doc researcher Linhua Shan in the third-floor seminar room. He then descended to the second floor and shot department head Professor Dwight R. Nicholson.

Lu exited Van Allen Hall, revolver tucked in his coat and headed west toward Jessup Hall.

In Jessup, he first shot student secretary Miya Rodolfo-Sioson. Then, he shot Cleary.

Lu ran upstairs into a classroom, where he hid. Before the police arrived, Lu put the gun to his temple and pulled the trigger. All of the victims, except for Rodolfo-Sioson, were targets on the list Lu had compiled. Lu was enraged about not winning a dissertation award that instead went to Shan, Lu’s former roommate.

Rodolfo-Sioson was the sole survivor of the victims, though she was paralyzed for the rest of her life.

Keller’s friend had told him on the phone, simply, shots had been fired at Van Allen. To the 20-year-old native of Muscatine, the interpretation was a gun had gone off. He didn’t know about the deaths in Van Allen and Jessup. He certainly had never considered the concept of a mass shooting on campus before.

“You don’t forget your first big story,” Keller said. “But this shooting had a visceral impact on this campus and town. It if happened today, it would just be another event in a long series of horribly routine shootings in the nation. Back then, it wasn’t an idea that had taken root in people’s minds. It was a shock. As a reporter, it was just what happened. It was a lot to figure out at night on a deadline.”

Keller grabbed his notebook and Sony Microcassette-corder, which he still carries in his car to this day, and headed up the hill toward the scene of the crime.

John Kenyon stands in his cubicle of the former DI newsroom in the Communication Center.

Nov. 1 1991 – DI editor

In Denver, then-DI Editor-in-Chief John Kenyon and then-Publisher Bill Casey were attending a national journalism conference. The two had arrived in Denver that Wednesday night. Casey called home to check in with his family that Friday evening. His young son, Will, answered the phone.

“Will picked up and I said, ‘How are you doing?’ ” Casey said. “And he said, ‘Oh, not doing very good. Mom called and told us to stay in the house, someone is killing people on campus.’ ”

Casey recalls hanging up with his son and trying to call the newsroom, but every phone line was busy. He went to find Kenyon.

“If there was significant news, you printed an extra,” Kenyon said. “This was pre-internet. No smartphones, no texts, no email. You saw it on TV news, heard it on the radio, or read it in a newspaper.”

For Kenyon, a young student editor with a young staff of college students who is now the director of the Iowa City UNESCO City of Literature, the hardest part was not being in Iowa City.

“I felt helpless,” he said. “I was hundreds of miles away, and I couldn’t do anything but call on the phone. It was really hard to digest, but they [DI staff] were a dedicated team of people who knew what they were doing.”

Lyle Muller stands in front of a memorial for the 1991 shooting victims on the south side of Van Allen Hall.

Nov. 1, 1991 — Covering the shooting

At Van Allen, Loren Keller arrived in time to see paramedics hauling a stretcher out of the building and police posted outside of the east entrance. The scene wasn’t frantic. There weren’t people crying or running around. All Keller saw were professionals doing their jobs — from paramedics and police officers to reporters and photographers.

“It was really quiet,” he said. “Most people on the street still didn’t know what was going on. I had some sense there were multiple victims.”

At one point, Keller tried to get into Van Allen.

“The police sort of pushed me back, so I hung out on the sidewalk with other reporters, just waiting and shivering pretty late until we got word that we would get the details at a press conference.”

Lyle Muller, then a reporter for the Gazette, beat Keller to the scene.

Muller, now the executive director of the Iowa Center for Public Affairs Journalism and the politics coach for the DI, was the Iowa City Bureau Chief for the Cedar Rapids Gazette in ’91.

Muller happened to be at Van Allen earlier in the day, reporting on a story about research the UI Physics Department was working on involving the plasma around asteroids. Muller had built up a stock of sources in the department, and that afternoon he was at the Gazette office. While filing expense reports, another reporter asked if he heard what the police scanner had said.

“The scanner said, ‘Shots fired. Van Allen Hall,’ ” Muller said. Muller told the reporter to call the photographer, and he left. “This was before cellphones, so once I left the office, I would have no way of communication.”

“As soon as I got there, I heard police sirens coming,” he said. Muller ran to the east entrance to get information from students as they came out of the building.

A Gazette photographer found Muller and told him people were shot at Jessup Hall. Muller headed toward the Pentacrest.

When he went around the corner, he saw police cars and ambulances lined up in a row in front of the Old Capitol, their lights illuminating the wintery evening fog.

“It was an eerie sight,” Muller said. “I went over to Jessup, and an officer told me to stay away because there was nothing anyone could tell me yet.”

Nov. 1, 1991 – DI photographer

At the Field House, then-DI Photo Editor Michael Williams — now the director of photography at The Everett Collection in New York — was photographing a UI swimming meet when an Iowa City Press-Citizen photographer got a call on his beeper and told Williams about the shooting.

By the time they arrived at Van Allen, night had fallen, and it had begun to snow. All Williams had was the camera equipment he took to cover the swimming meet.

“I was ill-equipped and experienced to shoot a fast-breaking, hard news story, but I flashed away in the maelstrom of first responders as EMTs brought what we thought was one of the victims out of the building into a waiting ambulance,” he said.

Later, Williams found out the person in the ambulance was someone who had passed out from the turmoil. He also discovered, much to his surprise, that his younger brother, a student in the physics department, had been in the basement of Van Allen during the shooting.

Annette Schulte sits behind her copy editing desk in the former DI newsroom in the Communications Center.

Nov. 1, 1991 – Shooting goes national

Eventually, DI editors got in touch with Keller at Van Allen when another reporter was sent to the scene, then headed back to the newsroom with information from Keller.

Then-DI Metro Editor Ann Hill, now a writer and researcher at SmartWorks Inc. in Wisconsin, said reporters filed into the newsroom as soon as word got around about the shooting.

“Reporters heard about the shooting and came in, wondering what they could do,” Hill said. “John and Bill were calling in from Denver, and Jim Arnold [’91 DI managing editor] came in, and we started figuring out what we needed to cover.”

As the night went on, the DI became a resource for media outlets across the country that were looking for the latest information.

“Other newspapers and places were calling in,” Hill said. “At one point, I was sitting next to Jim, and CNN called, and the two of us looked at each other, and I said, ‘That’s CNN, do you want to take it?’ ”

Arnold, now vice president of digital sales for Farm Journal Media in Kansas City, Kansas, said the shooting caused a lot of reporters to grow up quickly and become better journalists through the chaos that ensued in the newsroom as they tried to find out information for not only themselves but for national outlets.

“There were tears in the newsroom throughout the night,” Arnold said. “Some people knew the victims better than others. Mostly, we were pissed that this had happened. It was a dumb reason to take lives.”

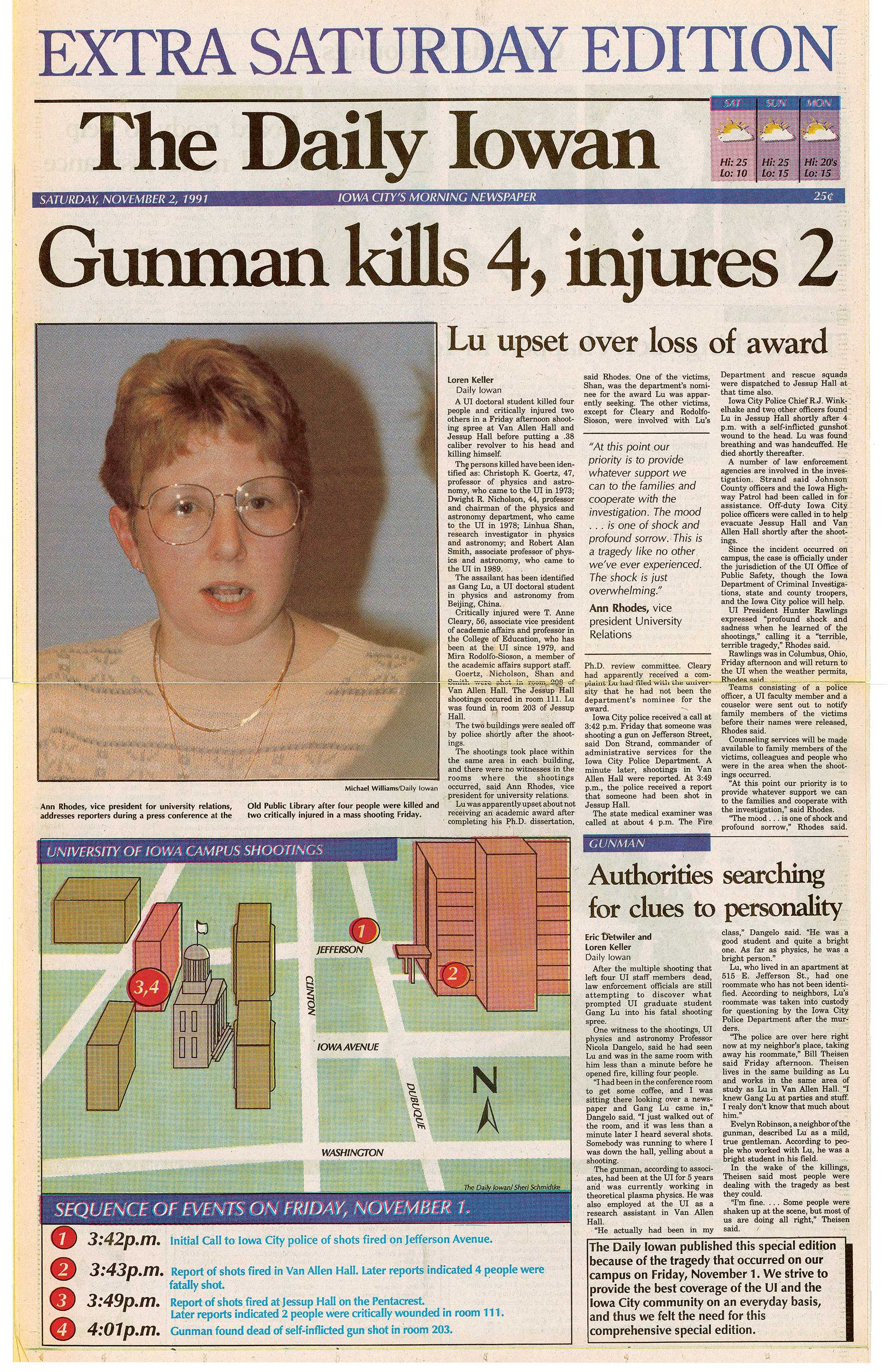

The Daily Iowan front page on Nov. 2, 1991.

Nov. 1, 1991 – Deadlines approach

Later that night, a press conference was held in which Ann Rhodes, the vice president for University Relations, addressed reporters. Keller, Muller, and Williams attended the conference. The photo Williams took of Rhodes ended up being the main image on the front of the DI’s special edition on Nov. 2, 1991.

“The press conference was difficult because national media were there and all these different people with different needs,” Muller said. “I needed every possible detail I could learn, and it was frustrating because everyone was interrupting everyone.”

After the conference, Keller rushed back to the DI newsroom to write an article about everything he had witnessed that night. The article was the main story on the front page, right next to Williams’ photo of Rhodes.

A memorial wreath and plaque rest in remembrance of the 1991 shooting sit outside of Van Allen Hall.

Coping with the aftermath

The acts of one student left an enormous scar on the UI campus. Family members and friends of victims along with members of the UI community were suddenly forced to digest the confusing and terrifying reality of it all.

The day after the special edition was published, Kenyon and Casey arrived back in Iowa City, and Kenyon attended the DI’s weekly planning meeting on Sunday to budget Monday’s paper. The dominant image was a photo of the flag on top of the Old Capitol at half-staff.

“It was before school shootings became an unfortunate part of our society and our culture,” Kenyon said. “That photo was our way of saying we were all trying to figure this out.”

Keller had Goertz as a professor in an astronomy class, and the shooting is an event in his life, and journalism career, that sticks with him.

“I think a lot about my astronomy class and Professor Goertz,” he said. “Around the anniversary, it tends to bubble back up. I walk by Van Allen and on the Pentacrest a lot, and it’s kind of in the back of my mind sometimes.”

Williams said the events of that November weekend made him realize he didn’t want to be a photojournalist who covers crime or breaking news.

“I didn’t want to be living with a police scanner by my bedside, running off at a moment’s notice to chase ambulances to the next incident resulting in possible loss of life,” he said. “I personally didn’t have the personality that could remain objective and focused in those type of circumstances.”

For Muller, every shooting that happens today reminds him of Nov. 1, 1991.

“That day is etched in my mind, and it’s also why when anyone makes some kind of threat on campus, us old-timers are jumpy,” he said. “Nobody paid attention to Gang Lu’s warning signs when he was saying things … and they wish they would’ve.”

On top of covering the events, Muller knew some of the victims. He knew Goertz and Nicholson from covering the physics department. He knew Cleary and kept in touch with Rodolfo-Sioson until her death in 2008.

“My view about every place changed,” he said. “Movie theaters, courthouses, churches. Is there someone there who could be upset? I found myself thinking darkly about that stuff after Nov. 1. It took a long time to get it out of my mind.”

Today, there are a few different memorials in Iowa City remembering the victims of the 1991 shooting. One is the T. Anne Cleary Walkway. Another is a plaque outside of Nicholson’s old office in Van Allen, now a meeting room named the Aurora Room. Under a tree on the south side of the building sits a wreath and a stone bearing the victims’ names.

“Every time I walk on the Anne Cleary Walkway, I think about it,” Muller said. “I go read her plaque, which is getting hard to read because it’s getting worn. I think about all the people walking there who don’t know who she is.”

Click below for more photos

[masterslider id=”144″]

On Thursday, Nov. 7, 1991, over 4,000 people gathered in Carver-Hawkeye arena for a memorial service, honoring the victims of the shooting. Then-University President Hunter Rawlings spoke at the observance, giving opening and closing remarks to the large crowd.

On Nov. 1, 1992, a year after the shootings took place, a crowd gathered on the Pentacrest for a moment of silence for the victims. The text below is from a pamphlet written for the one-year-anniversary event.

Note: This story is part of a series recognizing The Daily Iowan’s 150th anniversary. The series will highlight stories in the University of Iowa and Iowa City communities throughout the DI’s history. The shooting on Nov. 1, 1991, is not often talked about today; we felt it is time to recognize those affected and the locals who were there to share their accounts of the event.

Gage Miskimen would like to thank those quoted in the article for the interviews, meetings, and phone calls that took place the past few months, as well as the Special Collections Department at the UI Main Library for official documents that helped with the reporting process.

If you were there that day or have connections to the event and would like to share your side of the story via a forum, please email us at daily-iowan@uiowa.edu.