Coming full circle on Capitol Hill: How UI graduate Cheryl Johnson became the U.S. House Clerk

U.S. House Clerk Cheryl Johnson, a University of Iowa graduate, details her journey on how she became one of the highest-profile clerks in history.

April 11, 2023

For five days in January, U.S. House Clerk Cheryl Johnson was the most powerful person in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The House of Representatives is usually run by the speaker of the House. But in the battle from Jan. 3-7 to elect a new speaker, the burden of keeping order fell on the shoulders of the 1980 University of Iowa graduate.

Throughout the week, Johnson modeled an untarnished, calming appearance in her orange, white, and sometimes patterned tailored jackets as she presided over the oftentimes chaotic House floor. A brown gavel to her right, she stood poised and confident, calling for order with a firm voice when necessary.

Late last month, The Daily Iowan reporters and editors traveled to D.C. to interview Sen. Chuck Grassley, Sen, Joni Ernst, and Cheryl Johnson — among others. Johnson welcomed an editor into her expansive office where she spoke over an hour about her career on Capitol Hill.

This year, Johnson drew praise from both Republican and Democrat lawmakers for her steady leadership during the tumultuous election and received a standing ovation from over 430 members-elect of the House — a form of unity almost never seen.

Johnson called this year’s Speaker of the House election “democracy at work.”

“I think the nation got to see what the Office of the Clerk does, how the house operates,” Johnson said. “I think young people all across the country got a civics education that they otherwise wouldn’t have gotten.”

But Johnson’s role is beyond what was televised on national TV. She is in charge of 240 staff members across eight institutions. She receives messages from the U.S. Senate and the President when the House isn’t in session and acts as chief record keeper for the House.

So, how did the UI graduate with a journalism degree achieve such a prestigious role? Her journey to Capitol Hill actually begins where she was born: in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Cheryl’s Childhood

Johnson’s upbringing was defined by church rituals. While New Orleans has a significant Catholic population, Johnson and her family were active members of the Baptist church, a community which was at the center of their lives.

One of Johnson’s cherished memories is celebrating the Easter season. Beginning from Ash Wednesday to Easter Sunday, Johnson said it was the most solemn time of the year, and she would visit church and pray several times a week, and of course, practice for the Easter play.

When Easter Sunday finally arrived, Johnson said she would wear her best for the occasion.

“Always had a new dress, new shoes, new bonnet in your hair, new handbag,” Johnson said.

But Easter was only one of the rituals that Johnson celebrated. There were others that came before the biggest holiday of the year. Four weeks before Ash Wednesday, Johnson’s family engaged in Mardi Gras festivities, which included attending parades filled with giant character floats and carnival characters.

And Christmas certainly wasn’t forgotten by the Johnson family. For them, the winter holiday didn’t end until Jan. 6 with a King Cake: a round delicacy made with cinnamon-flavored dough covered in sweet frosting that marks the Epiphany. Its colors reflect those of Mardi Gras: green, purple, and gold.

Church rituals weren’t just the only highlights of Johnson’s childhood. She grew up in a household where homemade food was a love for her.

Her family’s labor-intensive recipes like jumbo crawfish and gumbo were always the meals which Johnson looked forward to sharing at the dinner table.

And Johnson’s family would jump at any chance to gather around the kitchen — like the evening that followed after her University of Iowa graduation.

Instead of eating out at a restaurant, Johnson’s family brought the food — and kitchen— to her. It was December 1980 and minus 10 degrees outside, but Johnson’s grandma still hauled all her cooking utensils and seafood ingredients from Louisiana to Iowa City to make a hot pot of her family’s homemade gumbo in her Mayflower Residence Hall kitchen.

“My friends, some of whom had graduated that day, [some of whom] wouldn’t graduate until May … boy did they come over to that little apartment in the Mayflower, and [we] had gumbo for days,” Johnson said.

Johnson graduates the UI in 3 ½ years

One of Johnson’s earliest memories at the UI was a mortifying moment during her freshman orientation. At the time, her mother was initially horrified that her daughter would be living in Burge because it was a co-ed dorm.

So, Johnson’s mom asked a question of Iowa’s dean of academics during a 1977 freshman orientation when hundreds of accepted Hawkeyes and their parents were in the room, namely: what was the UI’s STD rate?

“I thought I was going to go through the floor,” Johnson said with her eyes closed as if she was living the embarrassing moment all over again. “And he said, ‘Well, I will admit that it’s higher than we would like it to be. And we are certainly working to decrease that number.’”

Johnson’s first steps on the UI campus was actually during that orientation session.

The question Johnson said she’s gotten asked about 10,000 times, both during her time at Iowa and on Capitol Hill, is how did an African American woman like Johnson get from New Orleans — the Mardi Gras city known as a melting pot of French, American, and African culture — to Iowa City?

Her answer is always the same. In fact, Johnson can still picture the moment her high school teacher suggested considering the UI because of its top-notch writing programs.

“Cheryl, you should consider — you’re a very good writer — you should consider the University of Iowa that has a very good writing program for creative writing, but it also has a good journalism school,” Johnson said her teacher told her.

Johnson was co-editor of her high school yearbook, so the suggestion wasn’t a surprise to her.

The now-62-year-old knew she would go to college but didn’t expect to travel 811 miles to attend one. As someone who had a family-centered childhood, she called herself a homebody. Most of her family stayed in-state and went to schools like Xavier University of Louisiana or Louisiana State University.

Johnson’s excitement and decision to attend the UI came from her reading about the opportunities and education that the UI writing program offered. So, in 1977, Johnson traveled to Iowa City as the first in her family to get a journalism degree outside of Louisiana.

Iowa City wasn’t just going to be a cultural change without events like Mardi Gras parades — it was also going to be a change in climate.

A down jacket or parka? “Never heard of those before I came to Iowa,” Johnson said as she let out a small chuckle.

Snow boots? Her parents argued whether to get them from the Sears in Louisiana or Iowa. But her dad figured Iowa had better boots suited for the Midwest snow.

Despite being 811 miles from home, Johnson said she never felt homesick. During her first semester, Johnson remembers taking around five classes and was finished with her day by 3 p.m. While an early afternoon finish would leave many college students excited, Johnson was eager to take more classes.

Much like her childhood, Johnson liked having a rigorous schedule and found herself excelling with more on her to-do list.

At some points, she said she was taking seven classes — or around 28 semester hours — in a single semester.

“I just started taking more classes,” Johnson said. “I used to get special permission to take more classes, and the counselor was always like, ‘Okay, you know, you don’t want to overload yourself.’ But I found, the more classes I had, and the less free time I had, the more structure I had, I did better.’”

Johnson ended up unintentionally graduating in 3 ½ years, but her undergraduate career wasn’t just time spent on classes.

Like many college students, Johnson had her favorite traditions and experiences at the UI. She has fond memories of living at Burge, Stanley, and Mayflower Residence Halls, like the conversations she had with her first-year roommates who were from Michigan and Iowa.

Every Sunday, Johnson looked forward to eating at a downtown Iowa City restaurant or ordering a pizza because the dining halls were closed. She also joined a sorority and pledged Delta Sigma Theta, which at the time the UI housed the national sorority’s fourth chapter on the UI campus.

Tyna Price, a UI graduate and member of Delta Sigma Theta, met Johnson when she was initiated into the sorority in 1979.

Price called Johnson honest, straight-forward, and a hard worker, and considers her a part of her family. Since graduating from the UI in 1979, Price has stayed in contact with her old sorority sister.

In the same year Johnson joined Delta Sigma Theta, the sorority attended a national convention in New Orleans, and Price said Johnson invited her with seven other members to stay with her family instead of a hotel.

What Price remembers the most from her stay at the Johnson family’s home is their love of food.

“They’d cook breakfast for us before we left them … and we’d come back around five, and they would have cooked dinner,” Price said. “We had really good gumbo and fish, fries, everything that was associated with New Orleans.”

Johnson also dabbled in print journalism during her undergraduate years, which would be the only time she would work at a newspaper. Johnson was a copy editor at The Daily Iowan during her sophomore year, and she completed a 12-week internship with the Des Moines Register and Tribune Editorial Board during the summer before her junior year.

During the internship, Johnson wrote headlines for opinion pieces and a few book reviews. She even interviewed Sen. Chuck Grassley in 1980 during his campaign with the paper’s editorial board, and 40 years later, she works in the same building as Grassley.

Although the UI campus was a majority-white campus, Johnson said the university was a progressive campus and inclusive for minority students. Out of the 30,000 students at the UI, she said only about 1,500 were African American.

That’s certainly not a lot compared to 30,000,” Johnsons said. “But … it was a very cohesive body. And so, I always felt as though there was a critical mass of African Americans.”

Post-Grad School

Johnson attending Howard University, a historically Black research university, for law school was actually a fluke. Criminal defense wasn’t an interest to her. In fact, she just wanted to attend because she loved school, and getting a law degree seemed like the common sense choice after earning a journalism degree.

Johnson said her love for learning has roots in her high school years when she participated in a program called Upward Bound and stayed on a college campus for six weeks.

“I love the scholarship. I love research. I loved writing,” Johnson said.

Johnson could have stayed in Iowa for law school, but she had read that people tend to live in the city where they choose to attend law school. At the time, Johnson couldn’t see herself practicing law in Iowa because she didn’t see Iowa City needing attorneys.

“I just thought Iowa City was magical, and they couldn’t possibly have a need for attorneys because it’s just all students going to school all the time,” Johnson said she thought when she was 21 years old. “ I didn’t have the forward-thinking to think that Iowa certainly needs attorneys.”

However, Johnson didn’t just choose Howard University because she thought Washington D.C. was filled with lawyers. She also knew that there were many notable African Americans who graduated from Howard, such as Thurgood Marshall, a former associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, and Vernon Jordan, a business executive and civil rights attorney.

Johnson initially thought she would use her law degree to become an academician and teach. But after graduating from Howard, Johnson went a different direction.

After her graduation, a law firm in Portland, Oregon recruited her when she was at Howard. But a year later, Johnson returned to D.C. and enrolled in Georgetown’s Master of Laws program, which would take a year to complete and focused on specialized legal education.

But even after advancing her education in law and passing the D.C. Bar Exam, Johnson wouldn’t spend her career in court or at a law firm.

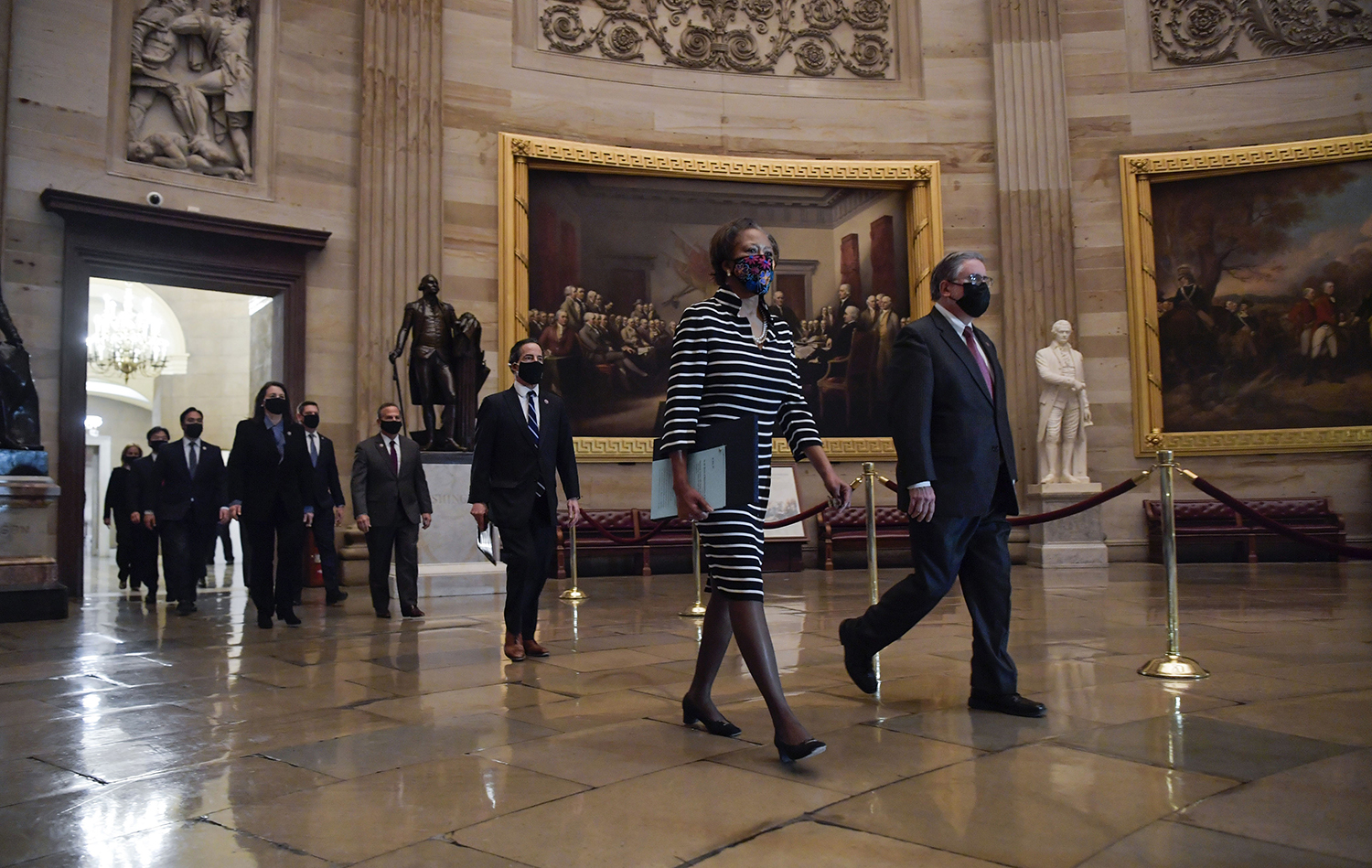

Jan 25, 2021; Washington, DC, USA; Clerk of the House of Representatives Cheryl Johnson (second from right), Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) (center) and Acting House Sergeant of Arms Timothy Blodgett (right) lead fellow House Impeachment Managers as they proceed to deliver the article of impeachment against former US President Donald J Trump to the Senate floor on Jan. 25, 2021 at the US Capitol in Washington DC.

Time on Capitol Hill

Most people have to begin in a senator’s personal office and work their way up to a committee.

But at 28-years-old in 1988, Johnson surpassed that expectation. She wasn’t just sitting on a committee when she started her first job on Capitol Hill. She was the House Administration’s Subcommittee on Libraries and Memorials staff director.

Johnson said she knew the St. Louis congressmen who hired her and called herself fortunate to start in an honored position.

The House Committee oversees the members’ pay. It oversees the members’ offices. It even oversees members’ parking spaces. In short, any administration of the House and how it operates fell under the committee — including the Office of the Clerk and ensuring that the gift shops and cafeteria was open.

The subcommittee that Johnson had jurisdiction over was the Smithsonian, which encompasses 21 museums and a National Zoo, while the other subcommittee had jurisdiction over the Library of Congress.

“Both of those entities get more than 80 percent of their funding from Congress, and so my job was to make certain that they were carrying out their mission given that they received congressional funding,” Johnson said.

Johnson’s oversight included ensuring buildings like the museum buildings were up to date and checking that animals in the Smithsonian Zoo received proper care.

After four years of serving as staff director, Johnson became the staff director of the investigations committee and oversaw federal education programs and funding for different parts of the program.

After 18 years working on Capitol Hill, Johnson left in 2006 to work for the Smithsonian Institution. What swayed her decision to leave? The building of a museum that meant a lot to her.

“I saw that the Smithsonian was building an African American Museum, which I knew because the Hill had passed the bill. And I said, you know, maybe I’ll go to the Smithsonian,” Johnson said.

Her official title was Congressional Relations Associate and she acted as a liaison between Congress and the Smithsonian Institution for 13 years while the African American Museum was being built.

Johnson found the experience fascinating because of the museum’s finances. She said the total cost to build was $540 million, and $270 was appropriated from Congress while the rest of the $270 million was raised by the Smithsonian.

Donations flowed in from all 50 states, and even from Hollywood stars like Oprah Winfrey. Beyond working with the finances, Johnson also loved working with museum curators and choosing the museum’s programs.

“I had never been in such a vibrant group of people who have degrees in museum studies and anthropology, and it was just a fascinating time,” Johnson said.

After the National Museum of African American Museum and Culture opened in 2016, Johnson was promoted chief of staff for the museum for two years before she left to return to Capitol Hill.

Becoming the House Clerk

Johnson said Nancy Pelosi called her in 2018 to tell her she wanted Johnson to become the House clerk. Johnson’s initial response to Pelosi’s suggestion was “What is the Clerk of the House?” She already loved her job at the Smithsonian.

But the more Johnson learned about the position and after talking with former clerks, the more humbled and honored she felt about the potential appointment.

So on Jan. 3, 2021, Johnson was sworn in by Pelosi as the 36th individual to serve as the House Clerk and calls the job an unbelievable experience. She is the second Black person and fourth woman to serve as clerk.

“It’s a very partisan time in the country,” Johnson said. “But [in] this organization, there are people who are committed to the institution. They don’t care who controls the House, or their thing is to make certain that the House operates and that members are able to fulfill their constitutional duties on a daily basis.”

Johnson oversees a staff of 240 people from reporters to historians across eight institutions. Some things about Johnson’s job are consistent. Every morning at 7 a.m. she receives an email saying that all the voting machines on the House floor are ready to operate. At 2 p.m., she’ll visit the House floor and confirm that all senators have their voting cards.

A lot of pressure lies on Johnson and her staff because accuracy is a crucial part of the job.. She has legislative operatives who tally the House’s votes and read all the bills. Her stenographers transcribe every committee hearing verbatim before the copy editor and reading editor to check for accuracy.

But there are some things about Johnson’s job that aren’t structured and unprecedented, like this year’s Speaker of the House election where folks were focused on her because she was reporting everything that was happening.

“This isn’t an incident where you’re at the Grammys, and you say the winner is one person, and then you come back and say, ‘Oh, no,’” Johnson said. “ Because when you announce who the speaker is, that’s who the speaker is. So those numbers have to be accurate … There were a lot of people behind me, behind the scenes, tallying those votes.”

Price, one of Johnson’s sorority sisters, said she admires how Johnson handled the election as it was televised on national television.

“She didn’t let them fluster her,” Price said. “She didn’t get upset. Some of those people were getting a little raucous in the air, but she handled herself very well.”

Price also called Johnson a family-oriented person and caring person, which she thinks are two characteristics that help her excel in her work.

While the job can be unpredictable, and she doesn’t always know when her or her staff will leave work, her favorite part of the job is interacting with Congress and other staff.

“I think members of Congress get a bad rap,” Johnson said. “They really are here to do a good job for the American people. When they are not here in Washington, they are still at home, working, and just hearing how hard they work for the American people is exciting.”

Jacquelyn Martin/Pool-USA TODAY NETWORK

Feb 7, 2023; Washington, DC, USA; President Joe Biden prepares to deliver the State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress at the Capitol, Tuesday, Feb. 7, 2023, in Washington, as Vice President Kamala Harris, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy of Calif., and Clerk of the House of the Representatives Cheryl Johnson watch.

Outside of her job

Johnson’s title as U.S. House clerk isn’t the only label that defines her.

She’s also a walker. Every morning from 6:15-8:15 a.m., she walks about six miles on the Capital Crescent Trail with her friends before heading to work, and she participates in half marathons on occasion.

She also considers herself an avid gardener since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when her neighbor offered her some seedlings. Today, her garden is filled with tomatoes, cucumbers, hot peppers, and jalapeno peppers.

Johnson also has a family. She is married and lives with her husband in Chevy Chase, Maryland, and raised a son.

She admits she’s passed down some of her traits to her 29-year-old son, who followed in her footsteps and graduated from Howard Law School. While she’s spent 32 years in public service, he works at a private sector law firm — but she considers him a writer like her.

“I was always, always making him write,” Johnson said. “As early as, as in grade school, I would have him rewrite things because the ability to write is so, so very important. “

Other hobbies, like cooking, that Johnson’s son picked up came from her family.

“My son, the men in my family, my brothers, my nephews, they have all taken up the cooking,” Johnson said. “And when men cook, they really put their heart and soul. My son really cooks well.”

Johnson admits she isn’t a cook herself, unlike her son.

Johnson said when looking back, she’s come full circle from a visit she took to D.C. at 15 years old to where she is today.

“I went in 11th grade, first time on an airplane, flew here to Washington D.C., and within two hours of us settling in, we literally checked in the hotels and came to Capitol Hill,” Johnson starts her story.

She was on a trip with the Close Up Foundation program that allows young people to stay a week in Washington D.C.

Johnson visited and sat in Barbara Jordan’s desk, who was one of her role models and the first African American woman elected to the U.S House of Representatives.

Johnson never met Jordan, but certainly knew of her. When Jordan was in Congress, she was known to take command as a member of Congress. She particularly acquired her reputation during the Watergate scandal in 1974 with her involvement in the hearings on former President Richard Nixon’s impeachment.

And she was reminded of that experience at 15-years-old during the Speaker of the House election.

“There was a lot of texting and Twitter and all of the other stuff that happened from Jan. 3 to Jan. 6,” Johnson recalls. “Someone [on Twitter] said ‘My commander in Those four days reminded her of Barbara Jordan.’”

Johnson said her son saw her tweet and brought it to her attention and told her that a stranger comparing her to one of the people Johnson admires speaks volumes of her character.

“I have a picture of me at age 15 sitting on the desk where Barbara Jordan sat in committee with her sign in front,” Johnson said. “I guess something really stuck with me when doing that week.”