From Suwanee to Iowa City: Tyler Goodson’s path to becoming Iowa’s All-Big Ten running back

Tyler Goodson, who calls Georgia home, was questioned upon choosing Iowa as his college destination. Now, the junior calls Iowa City home, too.

August 22, 2021

SUWANEE, Ga. — Football practice for a local youth team is winding down on an early August afternoon at George Pierce Park, a facility located in Gwinnett County, just north of Atlanta. A handful of parents dot the bleachers, watching their children on the field.

Waves of heat can be seen rising off the green turf as the temperature climbs well above 90 degrees. The stretch of pine trees wrapping around one half of the field doesn’t provide much respite from the midday sun.

There are five players on the field. None of them are any older than 13. A middle-aged coach instructs them all on how to line up in a three-point stance. He barks at them in his southern drawl.

A group of three approaches and the attention shifts to them. No wonder. It’s local idol Tyler Goodson — who not too long ago was practicing on this very same field. He stops to watch practice with his parents.

Iowa’s All-Big Ten running back leans on the fence, watching the young athletes go through drills. He dons a pink Champion shirt and black athletic shorts. Two gold chains hang around his neck and silver crosses dangle from both ears. He seems oblivious to the parents glancing at him and whispering.

Tyler arrived at this field nine years ago as a sixth-grader when his parents, Maurice and Felicia, relocated from North Carolina. But now this Georgian also calls himself an Iowan. And Iowa City has been his home for the past two years.

Tyler grew up in SEC territory. He was named the 2018 Georgia Player of the Year as a high school senior. Friends and family questioned why he’d want to head 834 miles northwest of where he grew up to continue his football career.

But to Tyler, Iowa felt like the obvious choice.

“Why Iowa?” Tyler recalls being asked, before answering his own question. “Because it felt like home.”

The Goodson family poses for a portrait in Suwanee, Georgia, on Aug. 1, 2021.

A football family

Hours before Tyler showed up at his youth football field, the Goodson family sat down for lunch at the Central City Tavern in downtown Suwanee, an upscale sports bar that opened before the start of the summer.

Tyler is seated between his parents on one side of the table, his back against the cushioned booth. He’s with his brothers, too. Taylor, a sophomore defensive back at Mercer University, sits across the table from his older brother, and Tavien, who is entering the 12th grade and attending an arts school this year, is at the end of the table.

Tyler and Taylor’s eyes wander to the handful of televisions in the bar playing the Summer Olympics and an Atlanta Braves game. Felicia and Tavien are posing for selfies together.

Food orders had just been taken when the first competitive football conversation of the meal started to heat up.

“Oklahoma is gonna get smacked,” Maurice said of the early reports of Texas and Oklahoma joining the Southeastern Conference. Apparently, Texas didn’t warrant a mention.

“Oklahoma and Texas could beat Missouri, Vanderbilt, the bottom of the SEC,” Tyler added. “They’re not gonna be able to compete week in and week out.”

“You don’t think Oklahoma could beat Auburn?” Felicia asked.

“No,” Tyler responded.

“So you’re saying Oklahoma would not be competitive in the SEC? I’m not buying it,” Felicia continued later in the conversation. “I believe Oklahoma would be competitive in the SEC.”

“No way,” Tyler said.

“You want to put your first NFL check on it?” Felicia taunts.

Tyler smiled and laughed off the comment as the argument settled down.

“This is how football conversations go in our family,” Felicia told me as I was spending the better part of two days in Suwanee with the Goodsons earlier this month.

“We’re all about football,” Maurice added.

From what Maurice and Felicia recall, Tyler has been all about football since he started playing at the age of 5.

Tyler later played baseball and basketball, and competed in track and field, standing out in all of them. Tyler still thinks he could take his good friend, Iowa point guard Joe Toussaint, in a game of one-on-one. But no sport was quite the same to Tyler as the first one he fell in love with — he even used to sleep with a football.

Tyler eats his two hot dogs and takes sips from water and lemonade while another football conversation — or, more accurately, argument — starts.

Taylor, jokingly, claims that Minnesota’s Mohamed Ibrahim — the conference’s leading rusher — is a better running back than Tyler. Then he takes it a step further.

“I was a better running back than you,” Taylor said, looking at his brother straight-faced.

“No you weren’t,” Tyler said, claiming his brother is exaggerating. “So that’s why you play [defensive back] now?”

The Goodsons are just as competitive with subjects other than football.

One year at a shopping mall around Christmas, Maurice challenged Tyler to a race after his son argued he was faster. Fellow shoppers started pushing tables and chairs out of the way and chanting as Tyler, at this time early in his high school career, beat out his father as they ran through the clear path created in the food court.

“I had on the wrong pants, I had on the wrong shoes,” Felicia said, mimicking Maurice, as Tyler points out they were both wearing jeans for the race.

Tavien is the only Goodson who doesn’t care for sports. When attending Tyler’s high school games, Tavien didn’t know what number his brother was wearing, and his only hope was that Tyler wouldn’t do anything to embarrass him — not that he ever did.

The rest of the family will still sometimes watch Tyler’s high school games, which they have recorded. They’re easier to watch now for Felicia. Especially now that two of her sons are playing college football, she starts getting butterflies days before a game even starts, hoping Tyler won’t fumble or that Taylor won’t get burned in the secondary.

Maurice flies to all of Tyler’s Iowa games. Felicia goes to most of them, too, just not the cold ones (“I love you, man, but it shows well on FOX, ABC, whatever you’re playing on,” Felicia tells her son). If there’s a magazine or preseason watch list that comes out involving Iowa or Tyler, his parents can’t help but read, especially if he’s on the cover.

“We have all the magazines,” Felicia said. “I’m probably worse than all of them [at collecting].”

Even the family dog, Delilah, a bichon frise and shih tzu mix that the Goodsons brought home about three months ago, has a small football chew toy by her bed.

Gwinnett County, where the Goodsons reside, is often referred to in the state as the “SEC of high school football” because of the area’s dominance. North Gwinnett High School is one of 25 high schools in the county, and many of those schools are packed with future college football players. Maurice said the local high school football environment is the closest thing you’ll see to college football at the high school level.

“We have so many kids in Gwinnett that get overlooked because there’s just so many of them,” Gerald “Boo” Mitchell, one of Tyler’s high school coaches and a former All-American wide receiver at Vanderbilt, later said to The Daily Iowan. “There are kids out there right now who are working at Walmart who just graduated who should be playing ball somewhere.”

The Goodsons originally lived in Forsyth County when they arrived in Georgia after Maurice took a new job. But Maurice and Felicia moved to Gwinnett County in large part because the football was better. They wanted Tyler and Taylor to face the best of the best.

And that’s what they did.

“I don’t think I really knew he was special, special until we got here,” Felicia said. “Because this atmosphere really forces you to pay attention because it is so intense … I knew he was good. But as a parent you can always think more of your kid than they really are because you’re the parent — you tend to not be objective. Then his junior year, I was like, ‘Woah. We’re onto something here.’ I think that’s when I really realized he could go a little further than we anticipated.”

Iowa running back Tyler Goodson poses with Gerald “Boo” Mitchell in Suwanee, Georgia, on Aug. 1, 2021. Mitchell, a former All-American wide receiver for Vanderbilt, is Goodson’s former high school coach and current personal trainer.

‘The SEC of high school football’

Just after 8 a.m. on a muggy Monday morning, Tyler and Maurice, both wearing black Hawkeye crewnecks with gold Tigerhawk emblems, walk into North Gwinnett High School, just a few miles from their Suwanee home.

They pass a framed 2017 7A State Champions poster in the hallway, which displays two photos of the team celebrating after the victory. Every player’s name from that championship team is listed on the poster. Tyler’s is there. Taylor’s is, too.

Outside, the school’s football field is in the middle of a remodel. New turf is being placed down only a few weeks before the new season is set to begin.

Bill Stewart’s face looks up from the play cards in front of him at his desk and he perks up as the Goodsons walk into his square office with white brick walls. Stewart was Tyler’s head coach during his junior and senior years of high school. Gerald “Boo” Mitchell, who still serves as a strength trainer for Tyler and was featured on an episode of his YouTube documentary series “Dreams 2 Reality,” is in the office as well.

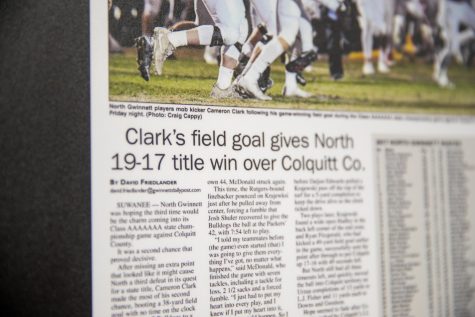

A framed newspaper clipping from the state title game Tyler’s junior year hangs right by the doorway into the office, and an enlarged photo of a championship ring can’t be missed on the back wall.

“It’s a big deal to have him around,” Stewart told the DI. “And it’s always good to have him back.”

Stewart recalls realizing pretty quickly after watching Tyler practice that he was going to be the team’s featured back. Before Stewart’s arrival, Tyler split reps at running back for North Gwinnett’s varsity team as a sophomore, the same season he scored his first varsity touchdown.

Maurice said high schools in Georgia usually only want players to play on one side of the ball. There was never any doubt that Tyler was going to play running back. It’s the position he had always played.

“I want the ball,” Tyler said. “I like scoring touchdowns. Why would you want to make a tackle when you could score a touchdown? That makes no sense to me. That’s the greatest feeling in football for me.”

The conversation in Stewart’s office quickly turns to Tyler’s junior year as a Bulldog, when he ran for 1,437 yards and scored 25 touchdowns.

Midway through that season, and with then-Samford assistant coach and future Iowa running backs coach Derrick Foster in attendance, Tyler suffered a high-ankle sprain and a turf toe injury. As the team neared the playoffs, Tyler didn’t know if he’d return at all the rest of the year.

“The whole time we’re waiting to get him back,” Stewart recalled. “And we didn’t know when we got him back how that thing was going to work. When you’re dealing with a toe, that’s a big deal for a running back especially. It was touch-and-go there. Uneasy.”

Tyler’s injuries mended, though. After missing four games, he returned for the playoffs. And he excelled.

In four games, Tyler rushed for 898 yards on the team’s way to a title.

“As far as a playoff run, I don’t think I’ve seen anybody have one as good, to where basically every game he’d make some critical run,” Stewart said.

The team couldn’t repeat in Tyler’s senior year. But Tyler ran for another 1,180 yards and 25 touchdowns to earn Georgia Player of the Year in 2018, an honor he didn’t even know existed until receiving it at an end-of-the-season banquet.

It’s now approaching 8:30 a.m. in Stewart’s office. The head coach has to run to a coaching staff meeting, but not before telling Tyler he needs to talk in front of the team sometime. Stewart exits into the hallway, walking by framed jerseys that belong to North Gwinnett alums who have turned professional. He sees the jerseys of offensive tackle and 2014 first-round NFL draft pick Ja’Wuan James and veteran NFL tight end Jared Cook, among others. Stewart teasingly said minutes before that Tyler’s jersey wasn’t hanging in that hallway, to which Tyler responded “not yet.” The Goodsons and Mitchell stay behind in Stewart’s office. Athletic Director Matt Champitto is in the room now, too.

Champitto, a Buffalo Bills fan, chats with Tyler about the hype surrounding former Hawkeye A.J. Epenesa in training camp. Then, Mitchell points out that Tyler’s attributes on the field are similar to New Orleans Saints running back Alvin Kamara, who he used to train.

Maurice emphasizes that this next season at Iowa could be the launching point to a professional career for Tyler. Maurice said eight to 10 NFL agents have already reached out to him inquiring about Tyler’s future as a professional. In May, ESPN NFL draft guru Mel Kiper Jr. ranked Tyler as the No. 4 best draft-eligible running back in the 2022 draft class.

Tyler was appreciative of the attention, but not overly impressed.

“It’s cool to be top-five, but I know I should be No. 1,” Tyler said.

“If I feel like there’s a running back better than me, then I’m not working hard enough,” he added. “I’m always going to think I’m the better running back, no matter who it is. It could be LaDainian Tomlinson, Reggie Bush — I’m the best running back in the world. That’s just how I feel. That’s how confident I am in myself.”

Maurice tells Mitchell he has to visit Kinnick Stadium for a game this season. Maybe the Penn State game, they decide.

Mitchell has yet to watch Tyler play in college from the stands.

“I just go to SportsCenter because I know he’s going to be on the highlights somewhere,” he said.

Mitchell always anticipated that he’d watch Tyler play college football — just not at Iowa.

“When he first told me about going to Iowa, I was like, ‘Why?’ Why are you going there?” Mitchell said. “He said, ‘Coach, I’m telling you, I feel like that’s where I’m supposed to be.’ I was trying to talk him out of it. Big Ten? I was on his butt about that. And I hardly ever do that to a kid. But he had no doubt that’s where he wanted to go.”

The Goodson family chats about Tyler Goodson’s journey from Georgia to Iowa City in their living room in Suwanee, Georgia, on Aug. 1, 2021. Tyler Goodson mentioned he never worried Iowa may be too far from home.

‘Why Iowa?’

At breakfast later in the morning after catching up in the coaches’ office, a folksy song by Uncle Kracker plays over the speakers at IHOP.

“This is the type of music they play in Iowa, right?” Mitchell teased Tyler. “I asked them to put this on for y’all because this is Iowa music. This is what I expect to hear when I’m in Iowa. As soon as I land in the airport, they’ve got this playing on a track that just keeps playing.”

Laughter followed as the group poked at the pancakes and omelets at the table.

“He’s gonna come downtown and be like, ‘Man,’” Maurice said to Tyler.

“There’s a downtown?” Mitchell asked as the back and forth continued.

Tyler is used to the kidding and questions relating to his decision to go to Iowa. He never really anticipated playing in the Big Ten, either.

After his playoff run junior year, dreams of one day playing college football were starting to become a reality. Colleges started reaching out the day after the state title game.

The Goodsons spent most of the gap between the end of Tyler’s junior year of football and the start of his senior year going across the country on recruiting visits, at some points making trips five or six weekends in a row.

They recall these recruiting stories back at their two-story home in Suwanee. Tyler, Taylor, and their parents are spread out along the couch in the living room.

Although they live in Georgia, the Goodson home is very much a Hawkeye house. Highlights of Joe Wieskamp’s college career had just been playing on the mounted television. In the ottoman in the center of the room, there are multiple copies of this year’s Athlon Sports college football preview, which features Tyler on the cover. Tyler’s alternate gold and Holiday Bowl jerseys are kept in a nearby room. Maurice is working on getting them framed.

Taylor, sitting right next to his older brother on the couch, makes fun of the fact that Seton Hill, a Division II school, was the first program to offer Tyler. Maurice, sitting next to Felicia on the other end of the couch, initially confused it for Seton Hall.

Smaller schools like Appalachian State, Ball State, and Georgia State were some of the first Division I schools to make offers to Tyler, a three-star recruit by most recruiting outlets.

Eventually, schools from the Power 5 conferences joined the hunt for Tyler’s commitment. Well, at least four of them did. The SEC? Not so much. In the entirety of Tyler’s recruiting process, Kentucky was the only one of 14 schools in the SEC to offer him a scholarship.

Georgia head coach Kirby Smart, the leader of Tyler’s home state’s marquee program, did have conversations with the Goodson family, though. Smart visited North Gwinnett Tyler’s junior year to speak with some defensive backs on the team. Those players suggested Smart also look into recruiting Tyler.

“‘I’m going to come back to see you this spring and I want you to gain like 10 pounds,’” Felicia recalled Smart saying to Tyler.

“Which is stupid,” Maurice said without missing a beat.

Tyler weighed 185-190 pounds in high school. But a common theme among SEC schools was wanting Tyler to bulk up to become a more downhill power back capable of surviving 30 or more carries each week. At Iowa, Tyler’s comfort zone is 15-20 touches per game.

“I’m a small back,” said Tyler, listed at 5-foot-10, 199 pounds on Iowa’s roster. “Everybody wanted me to be 6-foot-3, 6-4, 200-some pounds.”

“That would have taken him out of his natural gift, his element,” Maurice said. “We told [Tyler], ‘Don’t let nobody change you.’ You conform to their college system, of course, because that’s the system you’re in. But keep that same recipe the way you’ve been doing, just enhance it.”

Tyler describes himself as a versatile, do-it-all type of running back. That’s not the bruiser some SEC schools were looking for, but it’s exactly what Iowa wanted.

By that time, Derrick Foster had accepted the position as Iowa’s running backs coach, and picked up his recruiting of Tyler where he’d left it off at Samford.

According to Tyler and his parents, Kirk Ferentz and his staff’s pitch came down to two key elements — a chance to play early and to play a role similar to that of Akrum Wadley.

Wadley, with a similar build to Tyler, played running back at Iowa from 2014-17 and surpassed 1,000 yards rushing and 300 yards receiving in both his junior and senior seasons.

Instead of the traditional Iowa running back, built on running through tackles and punishing linebackers with a lowered shoulder, Wadley was shifty, making defensive players miss with his quickness and agility.

“We knew the skill set that he would bring to the table, that they saw and they were wanting now that Akrum was leaving,” Maurice said. “They said they wanted to change the whole running back game. They wanted to move away from the power type run. They brought Coach Foster in to put an emphasis on that, and Brian [Ferentz] was like, ‘Hey man, we need someone who can put their foot in the ground and take it to the house.’”

But Iowa’s offense would still be built around running the ball, which was appealing.

“We told him, you’ve some big boys [up front], two tight ends, a fullback, you’ve never had that,” Maurice said. “You have a higher chance of being successful there than going to the SEC.”

And if Tyler approached his freshman year correctly, he could have a chance to play that role right from the start.

Kirk Ferentz didn’t promise Tyler playing time, but told him if he worked hard enough, he could see the field right away.

“I think their pitch was that I had a chance to play early if I worked hard,” Tyler said. “And that’s what I wanted as well. That was basically their pitch the whole time — you can play early if you work hard.”

That wasn’t going to be difficult for Tyler, who by then was used to doing what it took to stand out on the field. He stopped drinking soda in sixth grade when his fourth-grade coach Brentson Buckner, now an assistant coach in the NFL, told him elite athletes don’t drink it.

One of Tyler’s mottos is that games are won in the summer, not the fall, indicating how devoted he is to bettering himself in the offseason. In addition to the strength and nutrition staff at Iowa, Tyler still has four personal trainers with different specialties — lifting, track, agility, and footwork. John Lewis, brother of former NFL running back Jamal Lewis, started working with Tyler in sixth grade, right after Felicia saw him working people out on “The Real Housewives of Atlanta.”

Tyler took an official spring visit to Iowa City in April 2018. Ferentz, the Goodsons said, was hesitant for Tyler to visit in the spring, when there was no football game to serve as a backdrop.

But Tyler wanted to sign before his senior year started, so he made the trip anyway.

The first impressions weren’t great, though.

“When we landed in Cedar Rapids and we started on the way, I was like, ‘Bro, no. There’s no way we’re coming here,’” Tyler said, looking at his mother as he recalled the empty fields he saw after arriving at the airport.

Felicia, the only person accompanying him on the trip, told her son to at least give the Hawkeyes a chance.

“We got to Iowa City and it was like, ‘This place is actually dope,’” Tyler said.

Tyler liked the smaller, tightly knit, college town atmosphere Iowa City provided. Felicia connected with the vibes of Iowa City and appreciated the Bluebird Diner grits she ate on the visit. Finding grits can be difficult up north, so she was pleasantly surprised.

Felicia reveals an inside joke she has with Iowa defensive line coach Kelvin Bell. She told Bell that Iowa City is America’s best-kept secret — a cool little college town.

“And he was like, ‘Yeah, and don’t go telling anybody because it only takes me like five minutes to get to work,’” Felicia said. “‘Don’t bring your Atlanta traffic here.’”

Tyler’s final eight schools came down to Kentucky, Washington State, Michigan State, Iowa State, Iowa, Wake Forest, West Virginia, and Nebraska.

Nebraska didn’t want Tyler to visit in the spring, either. But unlike Iowa, the Huskers refused to see him then, taking them out of the race. Felicia didn’t care for West Virginia coach Dana Holgorsen, which made the Mountaineers an unlikely destination.

Wake Forest, located in North Carolina near extended family, was appealing to Tyler. But not appealing enough.

In May 2018, Tyler told Iowa’s coaching staff he wanted to become a Hawkeye, but he didn’t publicly announce the decision yet. By July 3, he officially committed to Iowa.

“The main thing for me about Iowa and the recruiting process in general is just who was being real to me,” Tyler said. “Who would tell me what it was straight? When you go to all these places, they show you the glamour of the program — how many titles they’ve won, the facilities, but everyone has that. So it was just about who’s being real with me. Iowa was one of the main ones who was being real with me. It felt like home. It was an easy pick.”

Felicia described Tyler as loyal, which was good for Iowa. Because some power programs were seeking to snag Tyler away from the Hawkeyes.

“One of the things he told us was, ‘When I commit, I’m not decommitting,’” Felicia said.

Tyler said Clemson quietly offered him on National Signing Day. Michigan coach Jim Harbaugh, who had just lost out on another running back commit, also encouraged Tyler not to sign before visiting the Wolverines.

“Coach Harbaugh asked him to not sign on signing day,” Felicia said. “He said, ‘Can you just hold off on signing and let us get you on campus?’ And we’re like, ‘No.’”

“‘I’m gonna stick with my decision,’” Tyler recalled saying.

Upon his signing, Tyler was met with the question: Why Iowa? Friends asked him, as did teammates and some relatives.

And for every question, Tyler gave the same answer:

“It felt like home.”

Iowa running back Tyler Goodson carries the ball during the game against Nebraska on Friday, November 29, 2019. The Hawkeyes defeated the Corn Huskers 27-24.

Taking the reins in Iowa’s backfield

A collage of photos hanging in the living room of the Goodson home contains one of Tyler, Maurice, and Taylor attending the Iowa-Wisconsin football game at Kinnick Stadium in September 2018.

The game was Tyler’s first impression of an Iowa City game-day environment. It didn’t disappoint. And it wasn’t what he was expecting.

“Especially the fans,” Tyler said, still sitting on the couch. “It was crazy. Out of all the games I had been to, not one [fanbase] knew who I was except when I went to Iowa. They were out there shouting my name. When the game started, the energy, I was just like, ‘The SEC is not like this.’”

“We’d been to some pretty big SEC games,” Felicia said.

“Nothing like Iowa though,” Maurice responded.

Despite visiting Iowa City on Tyler’s recruiting trip, Felicia didn’t know much about Hawkeye fans when her oldest son committed. But shortly after Tyler picked his school, Felicia wore an Iowa shirt while driving in Georgia and realized that Hawkeye fans are everywhere.

“I was at a stoplight coming from work,” Felicia said. “And the lady did a honk-honk and yelled, ‘Go Hawks!’ And then she drove off. I was like, ‘Wow, there’s Hawkeyes here.’”

Felicia and Maurice are now fully acquainted with Hawkeye fandom. Both have thousands of followers on Twitter and are among the more well-known Iowa football parents.

“When fans approach me, they don’t talk about me, they talk about them,” Tyler said, pointing at his parents. “‘I love your mom and dad, they’re so awesome.’ And I’m like yeah, yeah.”

Tyler gets his fair share of attention, too. Fans send footballs, trading cards, gloves — anything they can think of to the Goodson home seeking his autograph. On campus, it’s common for a fellow student to approach Tyler in the middle of a lecture and try to make conversation.

If Tyler played everything right, he’d be playing in Kinnick in front of thousands of these devoted Hawkeye fans soon after joining the team as a freshman. But as he was working to earn his spot on the field, Tyler also had to adjust to living in Iowa City.

Tyler estimates it took him about a year to acclimate to life in the Midwest. Living through four changing seasons was different.

Felicia mentions she still has a picture from Tyler’s freshman year that he sent during the winter when it was below zero. Tyler snapped a shot of himself bundled up and simply wrote, “SOS.”

“It makes no sense how cold it is,” Tyler chimes in.

But other parts of Iowa City have been easier to adapt to. Yes, Tyler still prefers Georgia to Iowa (largely because of the weather), but he doesn’t mind his seemingly daily trips to the Get Fresh Cafe in Iowa City, where he gets an acai bowl. Pizza at Airliner isn’t bad, either.

Felicia interrupts the conversation with laughter when asked how to describe Tyler’s personality.

“Definitely not quiet,” Felicia said of Tyler. “Outgoing, never meets a stranger. Life of the party. Always laughing, joking, fooling around. Fun to be around, even as a kid. But when he doesn’t want to be bothered, he doesn’t want to be bothered. And you know that because he goes to his room and shuts the door.”

When Tyler got to Iowa, he figured out that shutting his door wasn’t always going to be enough.

Tyler points out that in the dorms freshman year, he had to take his name tag off his door and stick on a nearby room to prevent people from barging into his space and talking to him all night.

Tyler’s freshman year was full of learning experiences — on and off the football field.

When asked about his “welcome to college football” moment, it took him about two seconds to blurt out the name A.J. Epenesa.

“I ran up the middle and I was running high — I don’t know why because I never do this — and A.J. just completely like flipped me,” Tyler said grinning. “I was like, ‘Woah. I need to watch out for you, buddy.’ That was my wake-up call.”

It must have worked. In the first college game of his career, Tyler touched the ball 10 times. In Week 4 of that 2019 season, he fell three yards short of his first 100-yard rushing performance.

But Iowa went 2-3 over its next five games after a 4-0 start. Tyler didn’t exceed eight rushing attempts in any of the three losses.

“I knew there was a chance for me to play,” Tyler said. “But at times it would get frustrating because I could have been making plays and getting my momentum, but I’d get taken out so the other guys got their reps.”

Tyler’s coaches told him he was playing his role, which would get larger as the season went on. Tyler knew he had to earn the trust of the coaching staff over the course of his freshman season.

By the 10th game of the season, he had.

On the Monday ahead of Iowa’s game at Kinnick Stadium against No. 7 Minnesota, at the time 9-0, Foster pulled Tyler aside and told him he was starting. But he couldn’t tell his parents until the day of the game, per the coaching staff’s request. They didn’t want word to get out.

“That whole week I was nervous,” Tyler said. “In practice I would mess up plays, miss a protection I normally wouldn’t miss, drop the ball. I was like, ‘Bro, I’m starting this week. This is real.’”

Maurice was Tyler’s only parent in attendance for his first start. Felicia, not knowing Tyler was starting, was staying in Georgia to go to Taylor’s senior photos scheduled for that same day.

Wanting his mother to see his first start, but unable to tell her it was happening, Tyler started to implore Felicia to make the trip to Iowa City, telling her she’d probably want to be there for this one.

After Tyler denied that he was starting, Felicia attended Taylor’s pictures that Saturday, then went to the movies with Tavien. She might miss the start of Tyler’s game, she thought, but he wouldn’t be playing anyway, she figured.

“How do you miss the whole first quarter?” Maurice asks, interrupting Felicia’s story.

After leaving the theatre with Tavien, Felicia tuned into the Iowa game on her phone while getting gas and wondered why she was seeing Tyler on the field so much so early in the game.

“He’s playing?” Felicia remembers Tavien asking her.

Then, Felicia saw a text from her husband from earlier in the day informing her that Tyler was starting for the Hawkeyes. Tyler called Maurice as soon as he landed in Cedar Rapids that morning, and Maurice immediately texted his wife as he sprinted to his rental car.

“I got to campus in like 15 minutes, going 100 [mph],” Maurice recalls, only slightly exaggerating.

Felicia sped home, trying to listen to the game on the radio. She had to watch most of Tyler’s first college start on DVR.

“Mom, I couldn’t tell you because you would have put it on social media and they didn’t want anybody to know,” Tyler said, still trying to rationalize not telling her. Moments later, Felicia found out Tyler told Taylor early on.

With Maurice watching from the stands and Felicia catching up back in Suwanee, Tyler had quite the first collegiate start, even though he was shaking when he walked out of the tunnel. Displaying his dynamic running style, Tyler ran for 94 yards and his second college touchdown in Iowa’s upset win over Minnesota.

On Iowa’s first drive of the game, Goodson took a quick pitch to the left on a third-and-short, bursting outside for a 26-yard gain. On the second drive, Goodson bounced another run out to the right, stiff-armed two defenders, and powered his way into the end zone, reminding his parents of a similar run from North Gwinnett’s state championship game.

“Freshmen don’t do that,” Ferentz said at Big Ten Media Days, recalling Tyler’s runs from his first start.

By season’s end, Tyler became the first freshman to ever lead Iowa in rushing (638 yards). Last season, as a sophomore, Tyler was the primary back, compiling 914 total yards and seven touchdowns in an eight-game season shortened by the pandemic. Tyler earned first-team all-conference honors for his performance in 2020. But to him, that wasn’t good enough.

Individually, Tyler has his sights on the Doak Walker Award for his junior season, an award which goes to the best running back in the nation. He suggests that 1,500 rushing yards and 20 touchdowns should be enough to earn that honor.

“I know I can do more,” Tyler said, sitting up on the couch as his voice gets more passionate. “I know I can do better. [762 rushing] yards is OK, a good number. But it’s not good enough, especially if you want to go to another level. I always feel like I can do more. That’s why I can work so hard to be the best that I can be.

“This upcoming season is going to be different.”

Iowa running back Tyler Goodson poses for a portrait on the youth football field at George Pierce Park in Suwanee, Georgia, on Aug. 1, 2021. Goodson played at George Pierce Park in sixth and eighth grade.

Home away from home

Back at George Pierce Field in Suwanee, Tyler walks down the metallic steps of the bleachers onto the turf and roams the field with his parents.

“This is where it all started,” Maurice said.

Instantly, the Goodsons start recalling plays from Tyler’s youth football days. Tyler reminisces over a one-handed interception — from when he still played defensive back — even pointing out the hash mark where it happened. Maurice brings up Tyler’s 80-yard scoring run from last season’s game against Wisconsin and compares it to a scoring scamper of the same distance that saw Tyler zig-zag all over the field and into the end zone.

Felicia grins as she tells the story of Tyler arriving in Georgia on crutches after hurting his knee on the side of a swimming pool back in North Carolina. Still, when Tyler showed up for a youth tryout, he was picked over most of his other teammates. He had the look of a football player.

Tyler went from being the best player on this field to being one of the best players at his position across all of college football. If you ask Tyler, he is the best.

Tyler walks off the field and through the gate of the fence onto the pavement that leads to the parking lot. He remembers out loud the clicking and clacking his cleats would make on the cement while playing for his youth team.

“I always knew I wanted to play football,” Tyler said. “I didn’t know how far it was going to take me, but I wanted to play football.”

It turns out, football took Tyler to a state he never imagined living in, and a school that plays in a conference he didn’t know much about. Tyler heads to the parking lot, talking to his parents about leaving for Iowa in a few days for the start of training camp. A look of excitement takes over his face as he talks about the upcoming season.

For Tyler, Iowa City isn’t home. But it feels like it.