Stitch by stitch: costuming ‘The People Before the Park’

The University of Iowa Theatre Department's upcoming mainstage performance, 'The People Before the Park' is set in 1856 New York. For the past three months, the UI costume crew has been hard at work behind the scenes and in the Costume Shop, which has a unique history of its own.

March 14, 2021

Beginning next weekend, University of Iowa actors will dress in corsets, suspenders, and petticoats for the Theatre Department’s spring mainstage production, The People Before the Park. For many of these costumes, it has been a long journey to the stage.

Behind the scenes, a team of 16 individuals, comprised of both students and faculty, had a hand in costuming for the production. Eight of them have spent the majority of the spring semester working away in the Costume Shop, located only a few steps from the Theatre Building in the old UI Museum of Art. Soon their work will help transport viewers to 1856 New York, where the story takes place.

The People Before the Park, written by Keith Josef Adkins, focuses on the people living and working in the 19th century Black community of Seneca Village, which was eventually seized and razed by the city of Manhattan to create Central Park. Cast against the historical context of booming immigration to America, impoverished working-class slums in New York, and ongoing slavery in the South, the lives of Seneca Village’s residents are intertwined in the play’s plot, which explores art, love, and the inevitability of change.

From casting to the final dress rehearsal, the costuming team had roughly three months to assemble a whopping 110 individual costume pieces for the six cast members in the show, some pulled from storage and others bought or created by hand. The Daily Iowan followed the team’s process from beginning to end.

Threading the needle

On a sunny day over winter break, costume tailor Barbara Croy adjusted the skirt of a white dress pattern pinned to a mannequin inside the Costume Shop — the beginnings of a six-piece costume for the character of Phoebe, to be played by actress and MFA graduate student Britny Horton. Working from renderings and measurement information collected in the show’s “costume Bible,” Croy had spent the week cutting the pieces and pinning them in place, a step known as “draping” used to create initial mock-up garments.

Horton’s costume is one of the few that the shop “built” for the show, meaning most of it was pieced together by hand. Roughly 20 percent of costumes per season are made this way, said Costume Manager and Costume Shop Supervisor Megan Petkewec. The rest are bought, donated to the theater, or pulled from Costume Storage.

While “building” did not officially begin until January, work for the costume team began as soon as the show was cast in November. Measurements for all the actors were collected, costume renderings created by Head Costume Designer Loyce Arthur were printed, and Croy assembled everything into the costume Bible.

Arthur’s job was to develop the initial concept for costuming the show, keeping in mind historical context and what the script specifically called for. Because of the pandemic, Arthur designed the entire show remotely.

To make the play more realistic, Arthur wrote in an email to The Daily Iowan that she based her designs on photos of African-American women living in Seneca Village at the time, with the goal of reflecting the prosperity Seneca Village experienced and the many African-American professionals who lived and worked in New York. Some of the fabric for Phoebe’s dress came from New York City. Her day dress was made of cotton, while her “Sunday Best” is a taffeta, Arthur wrote. All skirts had crinoline petticoats (three-tiered ruffle petticoats) underneath.

The color scheme from the show was influenced by the work of African-American artists Henry Ossawa Tanner and Robert Scott Duncanson, Arthur wrote, which included bright colors created from new dyes invented at the time. Off-white, bright blue, and a variety of brown and orange garments collected on racks in the shop — organized by character — throughout January and February.

“You can see the colors of the landscape in their clothing – greens, browns, blues, etc,” she wrote.

Originally, the costume team had $3,000 from the show’s full production budget to buy, build, ship, and dry clean costumes. Petkewec said the pandemic made distributing funding different than in years past, however, with more of the overall production budget going to tech in order to film the show.

Petkewec said almost $200 of the total costume budget ended up going to scenic design, as during the pandemic, the price for wood had doubled — and metal tripled.

Filming has caused much of the theater world to adapt for the screen, and costume departments are no exception. To keep clothing from washing out under the lights, Petkewec said very light colors had to be avoided. The team opted for many off-white, natural, and textured pieces that fared better on camera under stage lights.

“We started a conversation with [Director of Theatre] Bryon Winn about doing a swatch test to find out how light we can actually go, or how many options we have if we can’t use those colors,” Petkewec said. “Are any of them too bright, too shiny, too tight a pattern?”

Getting hands-on experience

Of the 14 different Master’s of Fine Arts programs at the UI, only one area of study allows students to hone their skills in costume design: the MFA of Theatre Arts with a focus in Design, which also focuses on other aspects of behind-the-scenes work like set design and construction, in addition to costume design.

For these graduate students, mainstages are a real-world opportunity to build their skills. In a typical year, their costume ensembles would be viewed by thousands during the show’s run.

The Costume Shop gives general design and construction support to students for any particular pieces that need to be made. In addition to the graduate students and full-time employees, the shop has a fluctuating number of additional staff to help wherever they can.

First-year MFA student Abigail Coleman serves as one of only two graduate assistants in the Costume Shop. As part of the graduate program, students are required to work 10 hours per week in the shop. Coleman said that, as a part of her graduate assistant-status, working on The People Before the Park is simply part of her job.

For the show, Coleman was assigned to build two pairs of period-style long underwear. Costume crew members can also be assigned to a specific actor to complete all the alterations necessary for that character’s specific costume.

“It was a project for me that was in my skill level,” Coleman said. “That’s kind of how things get divvied up.”

Costume Shop Graduate Assistant Bethany Kasperek, a second-year MFA student, worked as Arthur’s assistant. Kasperek constructed a jacket for one of the actors playing a police officer.

Kasperek noted that, because a majority of the characters in The People Before the Park are male and the show is set in the 1850s, there were few pieces the costume crew had to make by hand. Items like pants, jackets, vests, and men’s boots are often already in stock or can be purchased easily online and altered, so there was a lot of time and effort saved. For a character like Phoebe, however, her wealthy status meant she would often be wearing dresses made of nicer material, which all needed to be built from start to finish using original designs.

“It really depends on what exactly the costume piece is and what needs to happen with it,” Kasperek said. “If they need like a pair of tearaway purple plaid pants, we’re not going to have that in stock, so we need to build it.”

Timeline by Parker Jones/The Daily Iowan

The graduate student also noted that, because of the safety restrictions in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been numerous changes to both the design and fitting process. If there were any in-person fittings, they were very brief, Croy said, but very necessary.

“You can’t adjust a cuff or a hem or a neckline without being up close and personal with the actors,” she said.

A unique workspace

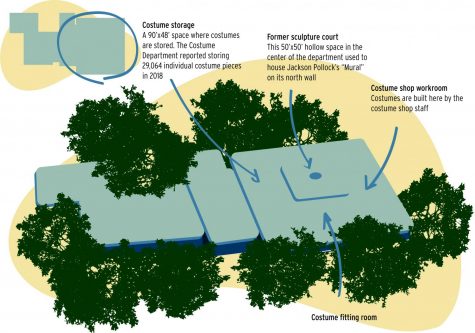

Being located in a former art museum poses challenges for the team in its unusual architecture, but Petkewec said she is personally grateful for the abundant space. Located in the southernmost half of the old UI Museum of Art, the usable rooms are built around a large, hollow square space near the building’s south entrance.

Though the 50-by-50 echoey cavity is now empty, it once served as the home to Jackson Pollock’s Mural. A faint white waterline over a foot above the floor marks where the flood waters stood for several weeks when much of the UI campus flooded in 2008.

The Old Museum of Art was once called “the last remaining casualty of the flood” by former Facilities Management Director Don Guckert. When the building filled with water, it permanently displaced over 14,000 individual works of art that would no longer be insured if they remained in a high-flood-risk area.

Because the building itself remained largely undamaged, however, it needed to be used for a different purpose. The costume department moved into the space in 2017; staff offices for the Stanley Museum of Art and theatre classrooms occupy the north half of the theater building.

“The costumes had been in the basement of the Theatre Building and had been flooded out, so they had to put us somewhere,” Petkewec said. “Like the things that had been in Hancher, all of that got moved out, then they had to figure out where to put us and our friends from the museum, and so we all ended up in this building together because it couldn’t be used as a museum again.”

Now, instead of art, the costume department stores over 29,000 individual costume pieces in its storage space, valued at over $1 million, according to the department’s last full inventory count in 2018. In the room’s center, rows of floor-to-ceiling double-decker racks are burdened with hangers full of tightly packed clothes. Each section is labeled in the event of another flood so that racks can be quickly evacuated and later reassembled in the same order as before. Surrounding the perimeter of the space are rows and rows of shoes, organized by type and size.

Everything is so well organized, Petkewec can immediately tell when something is out of place. While walking through “the hall of hats,” the shop manager quickly identified two that had been hung incorrectly.

Because the shop is a nonprofit entity of the state, all costumes within are considered state property and cannot be given away, thrown out, or sold, unless they are donated to another nonprofit or considered a “dead” garment that is damaged beyond repair. Petkewec estimated the stock increases by 100 pieces each season.

The final touches

On the evenings of March 9-10, the cast and crew for The People Before the Park gathered for final dress rehearsals. In the audience sat three cameras, ready to film the performance from all angles.

Golden light, representative of a hot sun, basked each costume in warmth, from actress Britny Horton’s brilliant tawny dress, topped with a lace-trimmed jacket and sunhat, actor Steven Willis’ plaid vest, worn over a billowing white shirt, and actress Kate Anderson’s blue polka-dotted dress and simple apron.

Backstage, a masked and gloved wardrobe crew of four assisted the actors when necessary, helping them get in and out of their garments. The process took a little longer in order to meet safety protocols, Petkewec said, but their duties otherwise remained the same.

All along, the costume team prepared for the next step. They changed out shirts for new ones that would work better on the camera and adjusted mask and microphone placement. As the end of filming neared, Petkewec watched the stage with a sharp eye, observing how each costume laid and moved on the actors.

Coleman said that her experience working in the shop and making garments as a graduate student is one she is very grateful for, and having a functioning theatre department during the pandemic is something she doesn’t take for granted.

“The department and university are doing an amazing job making sure everyone stays safe while still producing and creating amazing art,” she said. “I’m happy to have a part in it.”