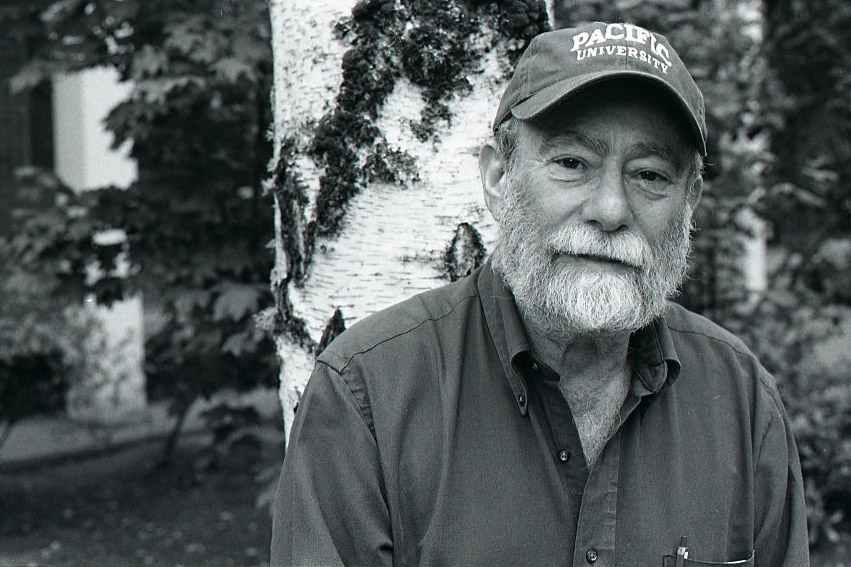

Friends, colleagues, students, and family reflect on the legacy of Iowa’s first Poet Laureate Marvin Bell

The poet and 40-year Iowa Writers’ Workshop professor died on Dec. 14 at the age of 83, having touched the lives of many and leaving a long withstanding legacy of written work in his wake.

February 7, 2021

In a soft navy vest over a buttoned shirt, poet Marvin Bell read his poem, “To Dorothy” on a couch in front of his MacBook. A pair of dark rimmed glasses bobbed atop his round nose as he spoke to the screen in a softened but confident voice, reciting the words as he had many times before.

“You are not beautiful, exactly. You are beautiful, inexactly.”

The subject of Bell’s poem, his wife Dorothy Bell, stroked his arm and back just out of sight as Bell closed the reading — a three-hour Zoom his friend, International Writing Program Director Christopher Merrill, put together in his honor in November. More than 600 people from all over the world attended to share their favorite poems by Bell, so many that the host of the event, Prairie Lights Bookstore, had to upgrade its Zoom subscription to fit them all.

Bell died a little over a month later on Dec. 14, after undergoing treatment for aggressive, late-stage stomach cancer since September. The poet was surrounded by his family when he died, the stereo playing “You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To,” by jazz trumpeter and singer Chet Baker.

Bell, a staple contributing member of the Iowa City UNESCO City of Literature, touched thousands of lives in his 83 years. He loved jazz music, soccer, witty wordplay, and long discussions about ham radios. His work is not only featured on bookshelves, but in college syllabi nationwide, and one of his poems, “Writers in a Cafe,” is even etched into Iowa City’s “Story Wall” in the Pedestrian Mall. The poem commemorated the city’s designation as a City of Literature in 2008.

Marvin served two terms as Iowa’s first Poet Laureate from 2000 to 2004 and spent four decades as a professor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop before retiring in 2005 as the Flannery O’Connor Professor of Letters. His book of poetry, A Probable Volume of Dreams, received the Lamont Poetry Selection of the Academy of American Poets, and he was a National Book Award finalist for his 1977 collection of poems, Stars Which See, Stars Which Do Not See. He is celebrated for his invention of the “Dead Man,” a character who appears in a long series of his “Dead Man” poems.

I just learned Marvin Bell passed away tonight and I am heartbroken. He taught me so much as a grad student, but more than anything, he taught me how to write a good love poem. What he wrote to his wife, Dorothy–those first two lines are absolute perfection. #RIPMarvinBell pic.twitter.com/BnvkdPbBPS

— Kelli Russell Agodon (@KelliAgodon) December 15, 2020

Writers around the world know Bell from reading his work in MFA programs or attending his live readings. For many others, however, Bell was a teacher, mentor, friend, father figure, and inspiration who left a vast legacy behind.

(From left to right) Nathan, Jason, and Dorothy Bell speak with The Daily Iowan in an interview on Saturday, Jan 30, 2021 at the Bell family’s house in Iowa City. The family revisited stories together in memory of Marvin Bell, who was the first Poet Laureate of Iowa and longtime Iowa Writers’ Workshop professor at the university.

“I like to think we have a world right here, and a life that isn’t death.” – Marvin Bell, “White Clover.”

Dorothy and Marvin Bell officially celebrated 61 anniversaries, but by the count they kept on a piece of paper on their fridge, they’ve actually had 169.

Each “anniversary” was marked by a delicious meal the couple once shared on the many travels they went on together around the world. When the day had been nice and the meal was good, it deserved to be celebrated.

The two started their count at 75 anniversaries, Dorothy said, both because they didn’t expect to ever have a 75th anniversary, and also because — if they did — they imagined they likely wouldn’t remember anything about it.

Dorothy recalled the memory with a laugh on a snowy January day in her College Street home, sitting on a couch in a living room draped with red curtains. Around her, the walls were covered in artwork — some gifted to the family from friends, students, and fans of Marvin’s work, some created or collected by Marvin himself.

The subject of Marvin’s most beloved poem was also the first person to read and edit most of his work. Some days, Dorothy and her husband would go back and forth discussing one of his poems, sometimes debating over a detail as small as a comma, her sons Jason and Nathan recounted in the living room that day.

To Dorothy, Marvin had a mind “like Einstein’s hair.”

“It was everything at once,” she said. “Going off on tangents all the time, and it shows in his work. It’s partly why his books are different, one book to the next.”

Jason Bell remembers hearing the click-clack of his father’s IBM Selectric typewriter in his study upstairs at all hours of the day. When he woke up in the morning as a young boy, his father would be writing down at the other end of the hall, punching away at the keys with two fingers. The typing would pick up again around 2 a.m., his father’s favorite time to write.

“He said it was the time when his mind let go of the practical things he had to think about, so he could just roam free,” Dorothy said.

Jason and Nathan Bell grew up while their father instructed at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. In the afternoons, Jason would sometimes come home from school to find the living room full of graduate students discussing poetry with his father. The students would turn to him with a smile and a wave, platefuls of snacks Dorothy had made for them sitting nearby.

“They were always in good spirits,” Jason recalled. “It was a writing workshop class, and you would have imagined that people would have been tense or feeling exposed in it, but it was always good humored and supportive in the atmosphere when I came through.”

Jason said his father was a supportive force behind his explorations and changing career choices, if not a bit of a worrier, when he left home to pursue an acting career in New York. On one cold winter day when Jason had first moved to the city, Marvin made a long-distance call to his son just to ask if he had remembered to wear his hat.

Even as Jason’s career shifted to multimedia production, his father continued to pop up through conversations with people he met, who recognized him as Marvin Bell’s son.

“When moments would happen when someone would recognize my father to me, there was an odd feeling of sharing him with the world, but it was always in a good way,” Jason said. “It was strange, but wonderful. It was like having a little bit of my father everywhere.”

(From left to right) Jason, Dorothy, and Nathan Bell speak with The Daily Iowan in an interview on Saturday, Jan. 30, 2021 at the Bell family’s house in Iowa City. The family revisited stories together in memory of Marvin Bell, who was the first Poet Laureate of Iowa and longtime Iowa Writers’ Workshop professor at the university. “He was kind and he was loving and he was affectionate,” said Dorothy Bell. “And these two are just like that. And also, they’re so super competent, they can handle anything that life throws at them. That’s the way Marvin was, that’s the way they are. They’re helping me get through this, because I couldn’t do it without them.”

Living to laugh

“You will be green again, and again and again.” – Marvin Bell, “Mars Being Red”

Nathan Bell remembers growing up in a household full of laughter. Sitting around the dinner table, he, Jason, and Marvin would all crack as many jokes as they could, trying to make Dorothy laugh. When he remembers his father, he remembers him laughing.

“I think of him as laughing and I always have,” Nathan said.

The 61-year-old folk singer shares the memory of Bell’s sense of humor with all who met the poet. Michael Wiegers, editor of the Copper Canyon Press — which published Marvin’s “Dead Man” poetry collections — said the poet’s natural sense of play was evident in everything he did. He distinctly remembers Bell’s laugh from when the two of them and Dorothy would spend time at the Bell’s small summer home on a bluff in Port Townsend, Washington, which overlooked the Port Townsend Bay.

“He had such a boyish laugh, a giggle almost, that he would break out in,” he said.

When at book signings for collections of his celebrated “Dead Man” poems, Marvin stamped each book with a little dancing skeleton alongside his signature, Wiegers recalled. The signings would be long affairs, he said, because Marvin would take the time to have a thoughtful conversation with each person in line.

Timeline by Parker Jones/The Daily Iowan

Even as he neared the end of his life, Nathan said his father remained remarkably composed, doing what he could to continue to bring joy into their home. When he got his father’s survivor’s information, he saw that Bell had drawn a caricature of himself, the same one he drew to end most of his letters written to his son. The caricature smiled up at him, holding a pennant that read, “It’s okay.”

“He just wanted people to be happy,” Nathan said.

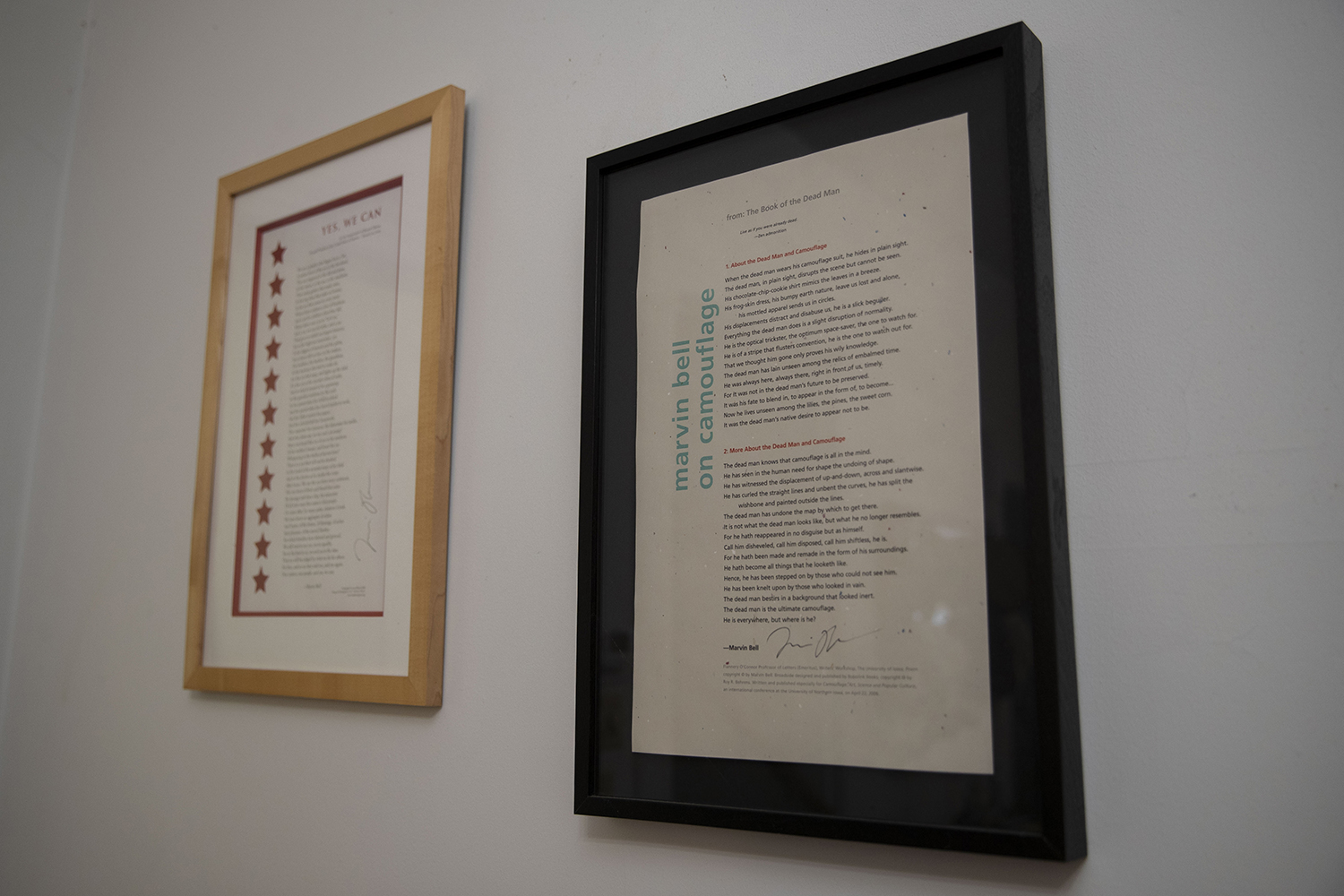

Frames of Marvin Bell’s poetry are seen on Saturday, Jan. 30, 2021 at the Bell family’s house in Iowa City. Around the living room, the Bell family decorated the space with gifts, prints by Marvin, artwork from friends, trinkets from their travels, and framed poetry by Marvin.

‘Marvin’s town’

“The espresso machine lets go the steam someone may write in the mirror. It is an impulse that survives disaster. The guns fail when surrounded by writing.” – Marvin Bell, “Writers in a Cafe.”

Christopher Merrill remembers befriending Bell over a series of early morning phone calls.

The International Writing Program director took a sabbatical leave in Santa Fe, New Mexico, a few years after meeting Bell at the Middlebury Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in 1978. Bell would call every morning at 8:30 to chat about life, poetry, and upcoming works.

“We just fell into the habit of talking on the phone every day, and that led to more and more things together,” Merrill said. “When I came here [Iowa City] in 2000, one of the things that excited me was knowing that I would be in Marvin’s town.”

Marvin Bell and me taking a break from a poetry workshop to spend a day in Yellowstone a long time ago. pic.twitter.com/XzIoFHQzRX

— Christopher Merrill (@CLMerrill) December 15, 2020

Phone calls turned into lunches where the two would joke, banter, and most importantly, Merrill noted, listen to each other. They collaborated for the first time in 2007 on a book to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the International Writing Program, the beginning of a series of collaborations between the two thereafter, including After the Fact: Scripts & Postscripts.

Executive Director of the Iowa City UNESCO City of Literature John Kenyon said Bell touched the lives of others wherever he went, whether that was dedicating his poetry to the city, reading his work at fundraisers, or taking the time to make meaningful conversation with everyone he met.

“He was just part of the fabric of the community, showing that poetry is just part of everyday life,” Kenyon said.

While away in the summertime, Marvin and Dorothy let former students and friends — many of them writers themselves — act as “housekeepers.” That generosity allowed many of their guests to spend time working on their novels in the Bells’ Iowa City home.

Many of Bell’s former students remember him as much more than a teacher. He was a mentor and for some, a father figure who cared deeply for his students. His former student Juan Felipe Herrera, who was named the 21st U.S. Poet Laureate in 2015, often tells the story of how he made the decision to pawn his beloved guitar one day when he desperately needed money. Marvin took it upon himself to buy the guitar himself and return it to him.

At the Zoom reading in November, Herrera said he still believes Bell was the person who brought him into the workshop to this day.

“[Bell] gave us a lot of freedom, and a lot of warmth, and a lot of friendship,” he said.

When he wasn’t teaching, Bell was promoting the work of his students, said Wiegers. The deep connection Bell made with each one of his students allowed him to advocate for them in a way many other teachers could not, he said.

“He promoted the work of poets who I wouldn’t have expected him to, who were writing differently than he was or had a different approach … and I think probably because he knew them personally, in the same way that he knew me,” Wiegers said.

An open laptop is seen on Marvin Bell’s desk in his office upstairs on Saturday, Jan. 30, 2021 at the Bell family’s house in Iowa City. The Bell family had left Marvin’s office space untouched, except for some cleaning they had done around the house.

Writing until the end

“The writing of a poem is, for me, an almost total act of abandon leading to discovery leading to recognition.” – Marvin Bell.

Whether it was letters to friends, poetry, or essays, Jason and Nathan Bell vividly remember their father writing every day.

The poet often worked in his study upstairs, but when young Jason or Nathan would invite friends over to play, Bell worked in a small annex in the backyard. The space was used by the house’s original owners to give Mormon missionaries a place to stay. There, Bell kept a second typewriter, and the Bells even installed a buzzer so Dorothy could notify her husband whenever he got a call.

After his sons had moved out, Bell wrote inside the house more often, penning his final collection of Dead Man poems on his MacBook at the dining room table.

The poet was collaborating with Merrill on their book, Here & Now, when the two conversed for the last time. The friends would often send one another paragraphs over email, and had a few exchanges on the day Bell told Merrill he had to go to the emergency room. Merrill had just sent him a new paragraph for the book.

“I love receiving each new para from you,” Bell had written back. “It defines the immediate future.”

A few hours later, Bell sent an email containing only one word after reading Merrill’s work, “Heartbreaking.”

Photo of Marvin and Dorothy Bell in Port Townsend, WA. Contributed by Susan Stenger.

During the Zoom reading in November, Marvin’s former student Naomi Shihab Nye said farewell to her teacher, reading aloud his poem, “The Last Thing I Say.”

“I hope you can feel some of the love and care you’ve sent out into the wide world coming back to wrap around you now,” she said. “I hope you know how strong it is.”

Nathan Bell sang and played his guitar. Jason Bell and dozens of others read that day, sharing their gratitude and stories. Marvin Bell addressed them all at the end, promising, as was his character, to reach out to each person who had read to thank them personally. The laptop he used that day still sits open on the desk in his study.

“Thank you,” he told them with a humble nod to his camera. “You’ve overfilled my heart.”