‘It was never the same’: Remembering the Oklahoma City Bombing 25 years later

Twenty-five years since what was the worst domestic terrorist attack in U.S. history, survivors of the Oklahoma City Bombing reminisce about the day an explosive parked at the north entrance of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building killed 168 of their friends.

April 18, 2020

Former Drug Enforcement Administration Special Agent Judy Hoke McCarver stood on the main floor of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, waiting for the elevator. It was about 8:30 a.m. April 19, 1995.

McCarver was heading to her office on the ninth floor before remembering she had already made plans that morning with the assistant U.S. attorney in another building. The 28-year-old turned away from the elevator and instead took the pedestrian tunnels running underneath the city to her meeting, which would begin at 9 a.m. and was the manifestation of months of culminating evidence, working undercover, and following paper trails. It represented a major case for her district.

Just two minutes into her meeting, McCarver felt the building shake. She and the assistant U.S. attorney looked at one another in confusion. She ran to the window, which provided a clear view of the street, where tons of glass had blown out of all the storefronts, and the windows on the ground floor of the building were busted out.

She looked further in the distance and could see buildings about five blocks west evacuating. If the county jail and courthouse were evacuating, McCarver said she knew it had to be something horrible. About that time, the attorney’s secretary ran into his office and said, “It’s the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.”

“In a split second,” McCarver said, “I was seized with terror.”

This is the story I have heard pieces of my whole life. Then Special Agent Hoke, or Judy McCarver as I’ve always known her, is my mom. And because she worked late the night before and everything that she needed for her meeting was already in her briefcase, she left the Murrah building the morning of April 19, 1995 without a second thought.

Half an hour later, a bomb parked in a truck by ex-soldier Timothy McVeigh at the building’s north entrance killed 168 people, including 19 children, and injured hundreds more. It was the worst domestic terrorist attack in U.S. history. Twenty-five years later, stories such as my mother’s continue to teach us about the ups-and-downs of survival, friendship, and never taking life for granted.

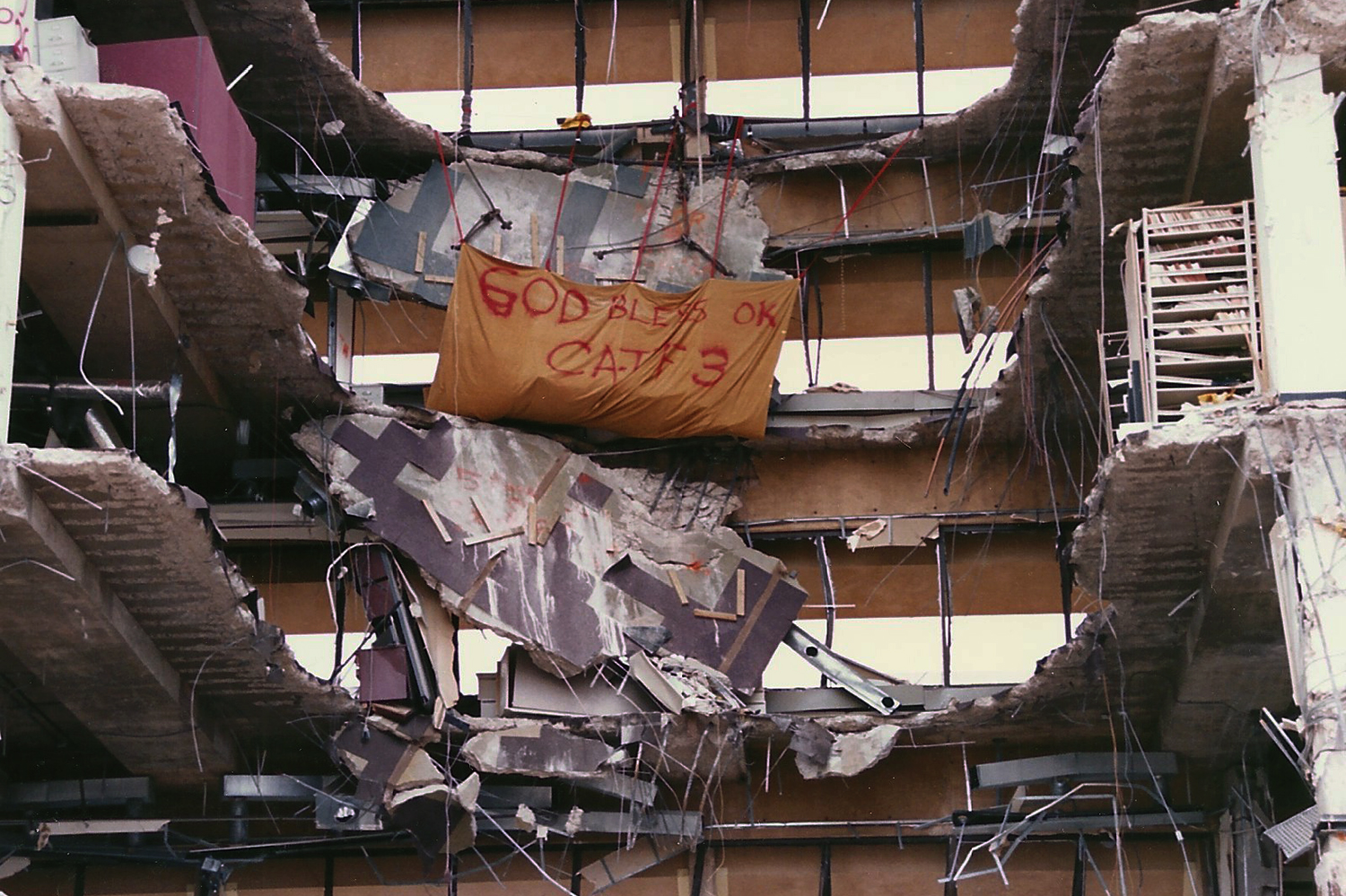

A destroyed section of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building’s north side is shown in the weeks following a bombing. The entire north wall of the building was obliterated at 9:02 a.m. on April 19, 1995 when a bomb at the building’s north entrance detonated, killing 168 people.

April 19, 1995 at 9:02 a.m.

Gina Bonny was sitting at her desk in the Murrah building and working on a report. She had just returned from the Drug Enforcement Administration office at the other end of the building and from visiting with its administrative staff — a group of women affectionately known as “the girls.”

Bonny, then a Midwest City police officer assigned to a DEA task force and often partnered with my mom, said when her computer began acting out of order she had the sense something wasn’t right.

“And then I heard the explosion,” Bonny said. “After that, it’s like I was asleep, and I woke up on my knees and my arms were above my head and there was stuff all on top of me.”

Her first instinct was that it was the end of the world, Bonny said. Her training, however, told her differently — it was a bomb. She stood up, took in the destruction around her, and located two members of the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms nearby, both alive but severely injured.

“One of them had something metal stuck down into his side, but it was stuck so I had to pull it out so he could get up. He was kind of bleeding, just a little bit everywhere,” Bonny said. “I get to [the other agent] and he had a pretty good-sized hole in his head and it was bleeding bad, so I’m trying to take his shirt off, so I can put the shirt in the hole to help stop the bleeding.”

Bonny helped them run down the nine flights of stairs to get out of the building. When she asked, someone on the ground told her they had not seen the “the girls.”

Meanwhile, McCarver remembers somehow running the four blocks back to her building. She never wore a dress to work, she said, but did that day because she was expected in the judge’s chamber for a case that afternoon.

Though her memory of those first few minutes remains fuzzy, McCarver said she made two calls. One to her office — nobody answered — and another to my dad, Paul McCarver, leaving a voicemail to let him know she was alive.

“He walked around to the answering machine, because he immediately has no idea where I’m at,” McCarver said with tears in her eyes. “And he sees one blinking light — and it’s my message.”

When she arrived on the scene, McCarver spotted an ATF agent with his head out the window on the ninth floor of the Murrah building. She asked him about her office and he just shook his head.

Then a DEA special agent and coworker of McCarver’s, Kevin Waters, had woken up late and been at home when the bomb detonated. He flashed his badge to pass the police tape and ran to the back of the building, where he was handed a phone to speak with the same ATF agent in the building. Waters simply asked in regard to his coworkers, “Did they suffer?”

In the chaos, Waters said he saw a police officer crying and carrying a baby. It was immediately clear the baby had been killed — he had never even known there was a daycare on the second floor of the building, Waters said. Nineteen of the people killed in the bombing were children, according to the FBI website. Fifteen of those killed had been dropped off at the America’s Kids daycare center that morning.

Bonny was still helping out on the ground when an attorney she knew approached her and asked if she was hurt. Covered in blood, Bonny answered that she didn’t know and let herself be steered toward an ambulance. On the way, she saw her husband.

“And of course he comes running up to me,” Bonny said. “He thought I was dead, so he was just so happy to see me. And I told him we need to go back in. The girls — we need to find the girls.”

A banner hangs from what remains of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building’s north side in the weeks following a domestic terrorist attack in 1995. In the aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing, a makeshift memorial was established at the base of the structure.

The aftermath

Crisis-recovery work was all McCarver did for six weeks after the bombing. She worked late every night, and often into the early morning. She did administrative work, and once spent a whole day driving cars out of the Murrah building’s parking garage. She was torn between work — her investigative instincts kicking in — and grief — trying to process the trauma.

Meanwhile, the DEA office in the city expanded and brought in new team members.

“It was never the same,” McCarver said. “It changed on a personal and a professional level. We had been traumatized in a way that they hadn’t … Before the bombing, we were a family. After the bombing, we were an office.”

Don Webb, then the resident agent in charge of the DEA’s Oklahoma City district office — known as “Boss” to McCarver and her coworkers — was at a charity golf tournament when the bomb exploded.

Amid the aftermath, Webb said first responders kept finding their belongings and bringing them to the command post. The flag from the DEA office was found nearly torn to shreds, he said, and is mounted in the Oklahoma City DEA office even today.

The last body was brought out 21 days after the initial explosion, Webb said. There was always something going on around the building, he added. People visited and volunteered by providing their time, food, and donations.

People sent in so many batteries and socks that first responders had to send out a radio message asking for less donations, McCarver said. Elementary schoolers sent letters to those affected.

Kari Watkins, Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum executive director, was living locally in 1995. When I spoke with her about the aftermath of the bombing, Watkins said she thinks her reaction was the same as every other Oklahoman — she wanted to help the recovery process, so she did.

“Then I went back to school and work, and that was that,” Watkins said. “We just went on when the time was right, and people started moving forward.”

The remnants of an office inside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building cover a section from floor to ceiling in the weeks following a bombing. The building was nine floors in height and housed several government agencies along with a day care center on the second floor.

Convicting Timothy McVeigh

Waters told me he could recall working late the night before the bombing. He left the Murrah building around 9 p.m. and saw a pair of strange men staking it out. They looked like hitmen, Waters said.

“It really creeped me out,” he said. “And it was a stare-down as I’m pulling out of the parking garage. I drove by, got their license plate, wrote it down, and called it in.”

Waters didn’t know it then, but one of those men staking out the building was Timothy McVeigh.

Just under two hours after the explosion April 19, an Oklahoma state trooper stopped McVeigh for driving without a license plate about 80 miles north of the city and arrested him for carrying a concealed weapon, according to the FBI website.

Jim “Buzz” Crist, a retired ATF special agent and one of four who worked the case with the FBI, said remnants of the Ryder truck that held the bomb led investigators to the man that had rented the vehicle out, who then gave them composite drawings of two suspects, one being McVeigh.

When they found McVeigh already in jail, Crist said his clothes were tested by an FBI lab that found traces of ammonium nitrate — a key ingredient in the 4,800-pound bomb.

An Oklahoma judge ruled after one year that, because of conspiracy theories running rampant in the state, McVeigh would not be able to receive a fair trial. The trial thus moved to Denver, Colorado, where Crist and his fellow agents worked the case two more years before McVeigh was found guilty and sentenced to the death penalty.

Crist worked with 100,000 pieces of evidence to convict McVeigh and his co-conspirators, Terry Nichols and Michael Fortier. Nichols, who helped mix and make the bomb, was sentenced to life in prison. Fortier, who Crist said was aware of the plot but neglected to report it to authorities, got 12 years, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

A former soldier that Crist said “went off the deep end” after failing to pass special-forces school, McVeigh was very anti-government. A government raid of the Branch-Davidian religious sect in Waco, Texas motivated the 27-year-old’s target of the Murrah building — where a few ATF agents who had participated in the raid worked. The standoff at Waco occurred April 19, 1993.

When Crist first saw McVeigh, he said he looked less like a villain in person than he did on television. He looked like a kid — a young soldier.

“He was a decorated war hero,” Crist said. “He was an outstanding soldier until he couldn’t get through green-beret school… I guarantee he always felt like he was the smartest in the room.”

For a month after the bombing, Waters didn’t remember seeing McVeigh that night before the attack. It wasn’t until the FBI routinely questioned DEA personnel about McVeigh that Waters said a light bulb came on in his head. The man who had been with McVeigh that night before the bombing was never identified.

The incident bothered Waters so much, he said he sought help with psychologists.

“I was in a bad place, because at that point I’ve got survivor’s guilt, and I’ve got the guilt of not doing anything to perhaps prevent it, having seen McVeigh and the other guy staking out the building,” Waters said. “And that’s coupled with how I didn’t even remember it for like a month.”

Twenty-five years of recovery

My mom and several of her coworkers had survived, “at least physically,” she said. Any given morning, there could be 20 people in the DEA office. But the day of the bombing, there were five. It was easy to wonder why, she said.

“We all had survivor’s guilt,” she said. “If you didn’t die, you had survivor’s guilt.”

She and my dad attended eight funerals in seven days. My mom gave eulogies for three of her five co-workers who died. So many of the funerals overlapped, they couldn’t always attend each one.

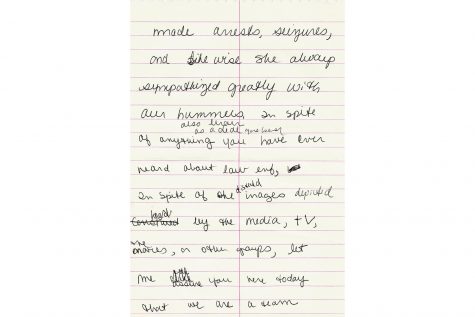

A page from a eulogy for a coworker of former DEA Special Agent Judy Hoke McCarver’s, scribed for a funeral after the bombing is written out on plain piece of notebook paper. McCarver gave eulogies at three of the five funerals for her coworkers who died in the bombing.

“It was sobering,” she said. “I never bought into what people would say, ‘Well, you were saved for a reason.’ I wasn’t saved for a reason. I have a reason for living, but I wasn’t saved for a reason. God didn’t save me and not spare [my friends]. It doesn’t work like that.”

McCarver said she eventually had to stop asking herself “why” the bombing happened the way it did and start asking herself “what.” She had survived — now what?

Bonny agreed, having sustained career-ending injuries in the bombing, undergone several surgeries, and been counseled for post-traumatic stress disorder. The bombing made her appreciate life more, Bonny said. When you see something like that and survive it, she said you try to remember not to take life for granted.

“My body is definitely a constant reminder of what happened,” Bonny said. “Sometimes I get negative, just feeling sorry for myself. But I’ve overcome that and remember that I survived, and my friends didn’t survive, and they didn’t get a chance to raise their children or see their grandchildren. And I always have to remind myself of that.”

Waters said the job wasn’t the same after the bombing. He began drinking, and was suicidal for three years after while still carrying his gun for the DEA. Waters said he wondered why co-workers of his who were “good” had died when he felt he was living a very “bad” life himself.

He decided to leave the DEA and eventually became a criminal-justice professor. Moving on was the best thing for him, Waters said. He’s over 20 years sober now.

Those affected by the bombing are never going to get closure, Waters said. But he has seen people like my mom, who he likened to a sister, accept what happened and reach a good place in regard to her fallen friends.

“You know, the memories of them don’t bring a tear to her eye, they bring a smile to her face,” Waters said. “And I’ve come to be like that too.”

Remembering the bombing

Every year in my house, April 19 was one of the few days out of the year I might see my parents cry. Even when I was too young to comprehend it fully, I could sense the helplessness they must have felt, which over the years has turned into a hopefulness, and the guilt that has turned into growth.

Terrorist attacks are meant to incite fear, but my mom said she doesn’t cower because of what happened. It simply made her want to live a life that is honorable to her friends.

“Twenty-five years is a long time,” she said. “And honestly there are days in my life I don’t think about what happened on April 19, 1995. And there will be other days where I’ll just have the most profound memory or moment. Twenty-five years is a long time, and there’s been a lot of water under that bridge.”