The Missing Piece: Continuing life without my dad

A missing father can leave children vulnerable to a dangerous lifestyle — how have these young adults dealt with it?

April 1, 2019

It was Nov. 20, 2012.

The evening passed by as I picked up clothes from my bedroom floor, listening to my parents’ chatter from the living room below.

It was the first night of Thanksgiving break during my freshman year of high school. I felt liberated having no responsibilities, normally feeling buried from my high-school workload. With all of my family close, I felt fully secure.

It seemed like we were making progress toward a brighter future, especially my 65-year-old dad, who had recently had surgery on his legs to improve his mobility.

Early in the next morning, my mom crept through my bedroom, calling my name. Barely awake, I stumbled out to the hallway, asking her if everything was OK.

She said she woke up to my father not breathing on his recliner.

I felt muddled because of my drowsiness, but I could steadily feel my heart falling into my stomach. I asked if he was all right.

“He’s dead,” she said, voice cracked.

Her sentence smacked me awake. How could he possibly be dead? Just last night, he asked me how my first play rehearsal went. The surgery was supposed to make his life easier. What went wrong?

When I walked downstairs, paramedics and police officers were already in my house.

I thought I was still dreaming. Numbness took control of my body. I couldn’t acknowledge this was reality. When an officer approached me and asked me if I was all right, I could only respond with a flat “Yeah.”

His body was taken out of the house. Filled with shock, I spent the remainder of the day alone, occasionally visited by immediate family members who brought me water.

I was 15 years old. I was in a critical part of adolescence where I needed my father the most, and he was just stripped away from me.

The following day, I went down to his bedroom and stopped at the recliner where he died. I took a seat and finally broke down.

At that point, I became a part of a disturbing statistic.

• • •

Throughout the United States, a notable number of fathers are missing from children’s homes, whether the father has died, left the home, or was never there to begin with.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 23.6 percent of U.S. children have lived in fatherless homes since 2014.

With nearly a quarter of U.S children growing up without their dads, it leaves them more vulnerable to a disastrous lifestyle.

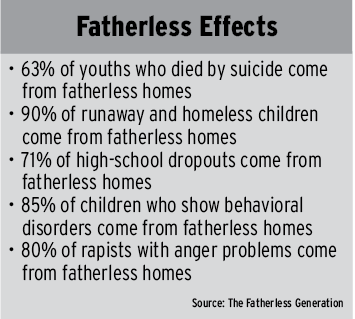

According to the Fatherless Generation, a blog dedicated to preserving fathers in homes, fatherless children are twice as likely to drop out of school. Children who have a poor or nonexistent relationship with their father are 68 percent more likely to smoke, drink, and abuse drugs. A 2003 article in New Scientist showed that absent fathers are often linked with teenage pregnancy.

Steve Nylin, the dad coordinator for the Young Parents Network in Cedar Rapids, helped conduct a 2016 study for fatherless homes around the area. Based on his findings, 5,158 homes in Linn County with children do not have fathers.

Despite these circumstances, many children learn to face the odds against them. I’d like to think I’m one of them, butother students at the University of Iowa have also risen to the challenges of growing up in a fatherless home.

• • •

Standing as the current president of Slater Hall, UI freshman Teagan Roeder enjoys reading and contributing his time to political organizations.

Growing up in Iowa City for a majority of his life, Roeder found himself here after tragedy struck his family.

When Roeder was 6 years old, his father died unexpectedly from a heart complication a few days after Christmas. He was only 40 years old.

Freshman Teagan Rodder poses for a portrait in the Main Library on March 14, 2019.

His family had moved from Germantown, Illinois, to Iowa City because his mother wanted her children to attend the UI, which was the alma mater of both of Roeder’s parents.

As Roeder grew up, he figured out he was on the autism spectrum, being nonverbal until age 4. Because of this, Roeder said, he found it difficult to form a relationship with his father while he was still alive. He said it further complicated his ability to emotionally deal with the loss.

During the first year after his death, Roeder became increasingly quiet while interacting with others, he said. Eventually, he started making stick figures which he would call “dad.”

Roeder said it’s problematic for so many children to be without their dads, especially because he couldn’t learn important lessons from his father.

“Boys need their dads, they really do,” Roeder said. “They need them to give them an extra source of confidence in their life. If there’s one thing I lacked throughout my childhood, it was confidence.”

• • •

While some children have struggled growing up in a fatherless home, others have learned to create better lives for themselves.

Walking into Cortado in downtown Iowa City, UI junior Alexia Sánchez wore her sweatshirt signalling her involvement in UI student government, in which she has served as a senator this year. Sánchez is from West Des Moines, where, she said, she has a huge support system from her family — without her biological father around.

Alexia Sánchez‘s portrait for UISG.

Originally born in Mexico, Sánchez said her parents separated when she was a baby because of her father’s abusive tendencies. At age 5, Sánchez moved to the United States with her mother and older sister. Never getting to know her father, Sánchez said, she never particularly missed him.

“I never thought there was anything missing from my family picture because my mom gave me so much love and did everything she could,” Sánchez said.

People have an embedded idea of what a family should look like, she said, and others should consider that every family looks different.

“We grow up with the idea of the perfect family being a mom and a dad, the kids, dog, and white picket fence,” she said. “For people to not meet that criteria that our society embeds in us, we’re always going to have the mentality that we’re not doing something right or we need to compensate for that by finding a husband.”

Knowing the numbers, Sánchez said, she’s grateful to be where she is in life.

“Statistically, I shouldn’t be here,” she said. “I shouldn’t be in college, I should be pregnant with one or two children now. For one reason or another, count me lucky, but I am where I am now pursuing college and having a really great support system.”

• • •

For women in particular, growing up without a father can leave them more susceptible to becoming sexually active at a young age or ending a marriage in divorce.

Sitting cross-legged inside her home in Martelle, Iowa, Hallie Corum, 21, comfortably looks back at her childhood. A stack of toys are placed a few feet away from us, shielded by a child safety gate. Raising her 1-year-old with the support from her girlfriend, Corum has experienced two generations of families without a father present.

When Corum was in third grade, her father was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, otherwise known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

When he was diagnosed, his doctor told him that he had a life expectancy of two years, but he lived for five.

On the day he died, Corum recalled, she and her family were watching a film when her father leaned forward, talking to himself.

When asked if he was all right, he responded with “I’m talking with that man right there,” supposedly talking to an angel, Corum said. The last thing he said while he was alive was “I’m almost there right now.”

Years later, Corum gave birth to her daughter, Leilani, although the father decides to not be present.

Currently, Corum is a full-time student at Kirkwood Community College studying to become a nurse. To balance school with parenting, Corum receives help from her family members to raise her child.

Now that she’s a mother herself, Corum said, she hasn’t begun truly grieving for her father until her daughter came into her life.

“This last year, it’s been hitting me a lot,” she said. “Since the day she was born, I just wanted my dad to see her face, because she has his eyes … she’s really skyrocketed me into grieving.”

• • •

While the father of Corum’s daughter continues to remain distant, local resources can help push fathers to step up to their responsibilities.

The Dream Center, a nonprofit organization in Iowa City, was started to combat the rising numbers of missing fathers.

Frederick Newell, the executive director of the Dream Center, began the organization because of his experience. Newell had a distant relationship with his father, saying he provided the basic necessities for the family but never became emotionally invested with his children.

The Dream Center is seen in Iowa City on March 14, 2019.

The Dream Center offers four different academies that involve families and child development, one of them being the Fatherhood Academy, which provides fathers counseling services regarding parenting issues.

Newell said there’s a notable disparity on missing fathers for both black and Latinx children, with 57.6 percent of black children and 31.2 percent of Latinx children in the United States growing up without their dads, according to theFamily Structure and Children’s Living Arrangements 2012. In contrast, 20.7 percent of white children live without their fathers.

A lack of father figures plays a key factor in the path of delinquency. For young boys in particular, they’re at a higher risk of crime and delinquency, according to a publication from the National Criminal Justice Reference Service.

Newell said boys growing up without their fathers will lead them into a similar path of negligence.

“We have this repeated cycle that is unable to be broken,” Newell said. “Once you get an education, you put yourself on a different path.”

• • •

My father was a subject I felt uneasy to discuss for years.

Since that day, I hardly brought him up in casual conversation. While meeting new people, the topic of parents will inevitably come up. If anyone ever asked about him, I’d typically give a vague response, simply stating that he’s not around in my life.

In a sense, I felt that if I pretended he never existed, I wouldn’t have to grieve over him any more.

I continued my next three years of high school, fully accepting that he’d never be at my graduation ceremony.

Once I began college, I started realizing how badly I wanted my dad around. Because I’m still in the transition phase

of becoming independent, I wish I could receive his nurturing guidance.

I’ve realized staying silent was disrespectful to my feelings. More importantly, it was disrespectful to his great legacy.

During my time with him, I couldn’t have asked for a more supportive and loving father. He always made an effort to be there, attending my cross-country meets, sitting in the audience during my shows, and reading all of my writing.

He’d always greet me with his warm smile, displaying one of his missing back-teeth. Looking at my own smile, I notice som

e similarities between us. Developing my personality, I’ve also inherited his stubbornness and surreal sense of humor.

He was a man of many talents, whether it was building me a playhouse or grilling the best meals. Undoubtedly, his biggest passion was music.

A devoted guitar player for years, I’d often see him perform on stage with his bandmates. Whenever I watch old videos of him playing, I could tell he was completely in his element, knowing that nothing could overthrow him.

Click below to watch John Stortz (far left) play with his former band, Raldo Schneider & Friends.

One piece of advice I remember him telling me is to never let my past affect how I view my future. I often joke about how my life is a mess, but in actuality, it could have gone downhill in several directions. Despite everything, I’m still here in one piece.

Uncertainty still lurks around my future, but I know I have plenty of growth I still need to achieve.

While my father is physically not with me anymore, he remains my biggest motivator.