As insulin prices rise, politicians attempt to take action, but for some families — it’s too late

Insulin prices have increased nearly 200 percent in nine years, and politicians are starting to take action. But for diabetics like Jesse Lutgen, efforts come too late.

March 12, 2019

Jesse Lutgen’s favorite pro-football team was the Green Bay Packers. They didn’t play in the 2018 Super Bowl, but he watched the Eagles clinch their first Super Bowl victory with his aunt on the last night of his life.

His mother, Janelle Lutgen of Bernard, Iowa, said through tears that her 32-year-old son Jesse, an avid football and baseball fan, could be described as being the best friend anyone could ask for.

Jesse died after rationing his insulin to treat Type 1 diabetes, a lifelong condition requiring injected insulin for the body to process sugar. He lost his job in the winter of 2017 and with that, lost his health benefits. He could no longer afford to buy insulin and died three months later.

Approximately 30 million Americans are living with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, and 6 million Americans use some form of insulin. In Iowa, 7.6 percent of adults have Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

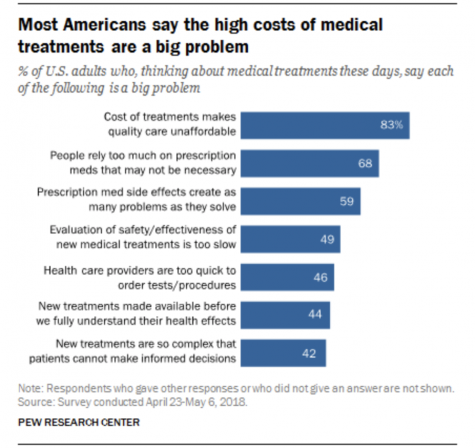

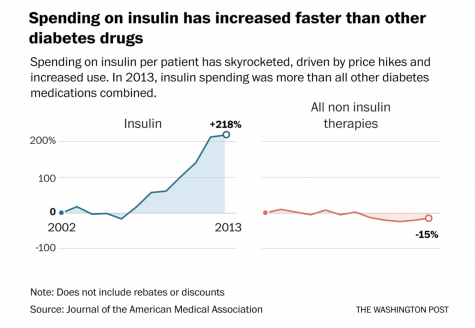

Many families such as the Lutgens have been unable to receive adequate medical care because of the rising cost of insulin. The mean price of insulin has jumped 200 percent from 2002 to 2013, according to a report from the American Medical Association.

Checkout this interactive video that showcases the surge in insulin prices over the years:

Averaged across types of insulin, the price of a milliliter of insulin in 2002 was $4.34. In 2013, that price increased to $12.92.

Some brands of insulin hiked prices at an even faster pace. Humulin, an insulin sold by company Eli Lilly, is one of six brand-name drugs that jumped at least 500 percent from 2006 to 2015.

Lutgen said her son was diagnosed at the age of 12, after he was med-flown from their small town to Iowa City after having flu-like symptoms for about a week.

“[Jesse] handled it pretty well. He didn’t wallow or pity or anything — that was just something that he had to do,” Lutgen said. “He was pretty easygoing.”

The family lives in northeastern Iowa in a town with a population of 117 people. The closest hospital is 17 miles away, in Dubuque. Lutgen said paying for her son’s insulin was never a problem until he was no longer covered under her health insurance.

The empty bottles of insulin she found in Jesse’s home after he died were from a friend who had extra, Lutgen said. Under federal law, it is illegal to sell or share prescription drugs.

“Who knows how much time it added to his life?” Lutgen said. “[Giving him the drug without the prescription] is illegal, but when you’re saving lives, who cares about whether it’s legal or not?”

Many patients, like Jesse, resort to rationing because they simply don’t have the money to keep up with regular dosing. When Type 1 diabetics don’t get the amount of insulin they need, they develop diabetic ketoacidosis, a condition in which the blood becomes acidic and the cells dehydrate. If untreated, it can lead to diabetic coma or death.

Lutgen, who also serves as the Jackson County Republican Party chair, said anytime she has the opportunity to share her and her son’s story, she seizes it. She said she wants to do more with her retirement than just be retired — she’ will continue to advocate for lower insulin prices.

What Iowa doctors and lawmakers are saying

Iowa lawmakers and endocrinologists are putting together policy recommendations to prevent other diabetic patients dying because they can’t afford to pay for insulin.

Sen. Carrie Koelker, R-Dyersville, who represents Janelle Lutgen in the state Senate, is sponsoring a bill that would allow someone to receive a one month’s supply of emergency insulin without a prescriber’s authorization. The current law in Iowa only allows up to a 72-hour emergency supply of a prescription drug, but insulin is not packaged in 72-hour quantities.

Koelker said she first heard Lutgen’s story at a campaign forum where Lutgen told the group about her son. Lutgen inspired her and other state lawmakers, both Republicans and Democrats, to work together on legislation that could help families struggling to afford insulin, Koelker said.

“There are people who decide, ‘Do we turn our heat on, or do we buy insulin?’ ” Koelker said. “ ‘Do we feed our children, or do we have to provide insulin? Do I ration this out for a week when it’s really a two-day dose?’ ”

The Senate bill unanimously passed the Human Resources Committee on March 7 and awaits debate on the floor.

“It’s not a cure-all, it’s not a fix-all, but it’s definitely a step in the right direction,” Koelker said.

A similar bill was filed in the Iowa House by Rep. Andy McKean, R-Anamosa, and Rep. Lindsay James, D-Dubuque. Koelker said that bill is “married” to the Senate version.

“Insulin isn’t a drug that you just take,” Koelker said. “It’s not like anyone is just going to pick up a vial of insulin and misuse it. When you need insulin, you need insulin.”

Dale Abel, a University of Iowa professor of endocrinology, said he and his colleagues are aware of the decisions patients sometimes make when they can no longer afford insulin.

Like other doctors, Abel warns against rationing insulin and said that insulin pricing is making it difficult for doctors to provide optimal care.

RELATED: Iowa parties weigh in on State of the Union

Abel said the price of insulin is a significant issue, and price increases have been addressed by professional organizations including the Endocrine Society, an international organization of which Abel is the president-elect.

“Drug companies will say that they give us very generous rebates that are available to patients to discount the price of business,” Abel said. “The trouble is that oftentimes patients may not know how to access these rebates.”

There needs to be more transparency in the pricing of insulin, he said, and with insurance companies and pharmacy-benefit managers, who negotiate the preferred pricing and rebates for any given patient. As a result, he said, patients with good health insurance typically pay lower costs.

“We would sometimes prescribe them an alternative form [of insulin], which may not be what we would want to use in the given patient, but we know may cost significantly less,” Abel said.

Bipartisan action on the federal level

Sens. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, and Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, say they hope Republicans and Democrats can come together for a bipartisan agreement at the federal level to address the rising prices of insulin and, more broadly, all pharmaceuticals.

Grassley, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, held hearings Feb. 26 with seven pharmaceutical manufacturers to address rising prices. The only insulin-provider among them was Sanofi. Grassley also wrote letters to leading insulin manufacturers, including Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi, asking for information regarding extreme price increases.

In an interview with The Daily Iowan, Grassley said he was frustrated with the outcome of the hearings, saying manufacturers placed blame on insurance companies and didn’t propose substantial solutions to the price increases.

Concerns about rising insulin prices have been showing up in Grassley’s emails and town-hall meetings in recent years, he said, and that the issue needed a “critical mass before Congress pays some attention to it.”

“There’s probably more opportunity for bipartisan agreement with doing something on prescription drugs, and specifically insulin, than almost anything else we have a chance to deal with, considering the Democrats have taken over the House of Representatives,” Grassley said.

Since Grassley submitted his letter to Eli Lilly, the company agreed to release authorized generic insulin to the market, which it will sell for half the price of nongeneric insulin. However, Greg Kueterman, the Eli Lilly director of communications, said in an email to the DI that the decision, made March 4, was unrelated to Grassley’s letter.

Ernst told reporters in a Feb. 28 conference call that a way to address the rising prices of insulin could be to bring in prescription drugs from other countries, where they are often sold at significantly cheaper prices. Kueterman said in an email that pharmacies from other countries can appear safe but quality standards may be lax.

Kueterman wrote in an email that Eli Lilly encourages patients to use their company’s help lines instead of purchasing outside of the U.S., where there is no FDA oversight.

In Canada, families affected by Type 1 diabetes will typically spend $1,500 after insurance in Canadian dollars ($1,116 in U.S. dollars) on insulin and medical supplies per year, according to the Canadian Diabetes Association. In the U.S., the annual average cost of insulin alone from 2012 to 2016 was anywhere between $12,467 and $18,494, according to the Health Care Cost Institute.

Ernst, who noted she has a number of family members who are diabetic, said she has cosponsored four bipartisan bills this year that aim to regulate how drug companies can put their medication on the markets by pushing for generics to be marketed faster and closing loopholes in patenting laws.

“This is a bipartisan issue, so we’re glad to be able to join some of our Democratic friends and working through these issues and trying to find a solution for the American people,” Ernst said in the conference call.

Being a student with Type 1 Diabetes

Most students are fortunate enough to not have to navigate the pressures of college with a chronic illness. But students such as University of Iowa junior McKenna Raimer depend on bills such as the ones in the Iowa Legislature and the U.S. Senate to ensure that she can access insulin.

McKenna Raimer, president of Type 1 Hawks the Iowa chapter of College Diabetes Network, talks to members of the Type 1 Hawks about the half price insulin made by Eli Lily that is not covered by insurence in a meeting on Wednesday, March 6, 2019.

Raimer, the president of the UI College Diabetes Network — Type 1 Hawks — said she has encountered new challenges in recent years because of changes in her insurance. She no longer has an excess of insulin as she was used to, and she has had to make every vial count “to the last drop.”

RELATED: UI research leads to possible treatment for diabetes, fibrosis

UI sophomore Maddie Walding, the vice president of Type 1 Hawks, said the Type 1 community online and on campus has helped her transition into college as a diabetic.

“I’m very independent with [my diabetes], and the hardest part is just adjusting to everything because insulin needs change drastically throughout your lifetime and that includes coming to college,” Walding said. “I would be walking to and from class, and it would just be like ups and downs with my blood sugar.”

When diabetics’ blood sugar gets low, they can experience fatigue, have difficulty concentrating, and endure mood swings. In some cases, Type 1 diabetics can experience insulin shock, a life-threatening condition. Walding said blood-sugar changes are unpredictable, and that keeping blood-sugar levels stable can be difficult because she has no choice but to stop whatever she’s doing to address it.

“You have to stop yourself in the moment and say, ‘No, I’m going to take care of myself right now and fix it,’ ” she said.

DI films sat down and interviewed UI students who struggled with the everyday challenge of diabetes. Checkout this video:

Raimer said she feels a lot of pressure for her to find a job with good health benefits.

“Eventually, I will be off my parent’s insurance,” she said. “… I have to worry about not just ‘I need a job when I’m out of college.’ It’s, ‘I need a job with good health insurance,’ because I can’t afford it on my own.”