Debby Bell, 59, of West Liberty, stands for a portrait outside the Burge Hall Marketplace on Friday, February 1, 2019. Bell works for UI Housing and Dining in order to cover the cost of her husband’s medical bills.

Working for a living — and health insurance

Health insurance and retirement packages don’t always cover baby boomers’ necessities, forcing them to continue in the workforce despite being at, near, or beyond retirement age.

February 8, 2019

This story was co-published with IowaWatch.

A 58-year-old Iowa City man has Stage 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, an intense respiratory failure that requires him to rely on an oxygen machine around the clock and prevents him from working. Much of his costly medical expenses for this disease, widely known as COPD, aren’t covered by his health insurance.

So, 59-year-old wife Debby Bell uses her health benefits as a University of Iowa employee to cover the cost of his checkups, prescriptions, and medical machines that supply him oxygen and stimulate normal breathing. One prescription is for an inhaler that costs more than $500 a month. Checkups are required every six months and require a $1,500 echocardiogram.

“There’s no way a normal person can pay that,” Bell said. “Even someone with a much better job than I have … you could go broke real quick.”

Bell is one of many Iowans at retirement age driving an increase in the number of older workers — many remaining in the workforce because of the high cost of health care that their life savings cannot cover. The Pew Research Center reports that 10,000 baby boomers hit retirement age every day.

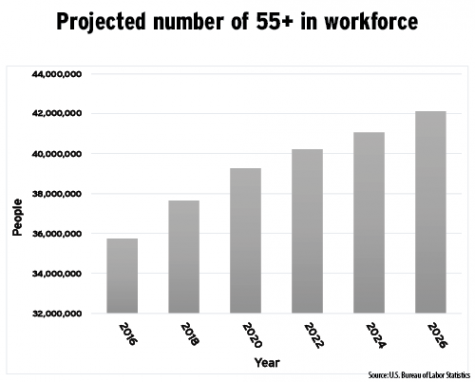

The youngest are starting to retire at age 54, according to the senior advocacy group AARP. But most aren’t leaving the labor market. An estimated 9.7 million Americans age 65 and older were in the U.S. workforce, the U.S. Census Bureau reported last year. Approximately 41 million people of the 150 million participating in the workforce were baby boomers, according to a 2018 Pew Research Center study. The number of boomers in the work force shows a steady 4.5 percent increase since 2014, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports.

Bell and her husband, Jeffrey Bell, live in West Liberty. Without the health benefits that go with Bell’s employment at the Burge Marketplace, the couple would not have been able to pay their mortgage or utility bills, she said. She is approaching retirement but fears it won’t be an option if she doesn’t have decent health insurance to supplement Medicare and cover prescription medicines for her and her husband.

When Bell was hired in 1983, the university offered her the same insurance and retirement package that professors at the university get. She took it.

“The insurance we have here at the university is a lot — it’s very good,” Bell said. “And if it wasn’t for that, we probably would’ve been homeless. We would have had to get rid of our house and sell everything that we had because of medical bills.”

Bell is part of the baby boomer generation born between 1946 and the early ’60s, following World War II. Since then, health-care options in the United States have grown, allowing people to live longer, healthier lives.

Retirement age is relatively subjective, and while most retirement plans in the United States set the bar at 65, the AARP defines its requirement for membership at 50 and older. Social Security retirement benefits don’t kick in until 62, and Medicare health insurance isn’t granted until 65.

Debby Bell is skeptical about her hopes for retirement in the near future because retirement packages aren’t always secure. The decline of pension funds after the economic depression in 2008 led to a real concern for baby boomers’ life savings, said Cal Halvorsen, an assistant professor of social work at Boston College. He studies the experiences and outcomes of individuals who work later in their lives.

“Combined, you should have a financially secure savings fund,” Halvorsen said in a phone interview. “Pension funds are declining, though, and older individuals have to rely on personal savings and Social Security. Some of these individuals are in poverty and are forced to re-enter the workforce.”

Bell said she doesn’t have the luxury of dipping into personal savings because that money pays to care for her husband’s Stage 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He is on a 24-hour oxygen defibrillator to ensure his respiratory system doesn’t fail him, contributing to his perpetual state of dependency on medications and medical equipment to keep him alive and as healthy as he can be.

While Bell works to pay for her husband’s health care, she said, she also enjoys her job. Working at one of the university’s dining halls has exposed her to new experiences and diversity in people that she appreciates.

The exposure to a younger demographic at UI Dining is one she appreciates, and she said that while she doesn’t experience outright ageism, she struggles to keep up with technological advancements. Her younger coworkers help her with this barrier and teach her what they can, and she returns the favor by giving advice from her long experience in dining work. University Housing & Dining pairs younger workers with older ones to guide each other at work and learn life skills from each other, said Kelli Haught, Catlett Marketplace dining operations manager.

“Age isn’t a factor in hiring,” Haught said. “It’s more about what qualities a person can bring to a certain position. With that being said, the qualities that I look for when hiring cooks is that they are dedicated and have experience. Older people often bring that to the team, and they help to teach our younger workers life skills and guide them in their side-by-side work relationship.”

But UI social-work Professor Sara Sanders said most people she’s encountered work because of poverty. In Iowa, approximately 326,636 people live below the poverty line, according to the Census Bureau. Many are caregivers and work on top of that to combat income disparity.

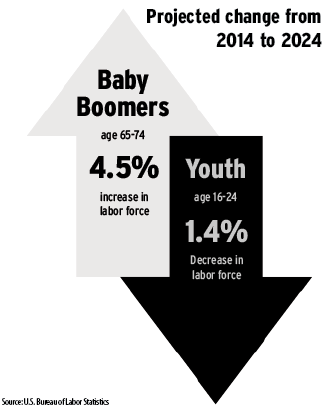

The continuation of older workers in the labor market has brought about suggestions that they are replacing younger workers, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics report that forecasts workers ages 65 to 74 will increase by 4.5 percent and workers aged 16 to 24 will shrink by 1.4 percent. However, there is a different reason for this trend, UI economics Chair John Solow said.

The decrease in younger workers exists because the nation’s birth rate has gone down, he said, and women are waiting longer to have children. The labor market is now driven by a rebound in jobs since the great recession in 2008 and a growing supply of older workers. The unemployment rate in the United States is 4 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, showing the economy and job placement has been growing steadily since the recession.

Businesses and organizations must consider the needs of older people who keep working, said Rosemary Thierer, the executive officer of the Iowa Department on Aging. For example, many older workers need a flexible schedule and part-time hours, because most of them are caregivers for other elderly people.

Thierer said baby boomers have worked basic jobs in sales and food service and made an OK income at $7.25 per hour after returning to the workforce. However, a lot of them cannot afford to retire. Meanwhile, Thierer said, Iowa is desperate for workers. While the unemployment rate in Iowa is 2.4 percent, the average age of an Iowa worker is higher than the national average, according to the Center on Aging and Work. That means older workers not only are working longer but are the primary market for employers in Iowa with a 66.8 percent participation rate in the workforce.

“One of the reasons that McDonald’s are choosing older workers is because they are showing up,” Thierer said. “Older workers are more reliable than younger workers, and they can have positive influences on the younger workers. It’s important for all the generations to work together in the workforce because they can all learn something from each other.”