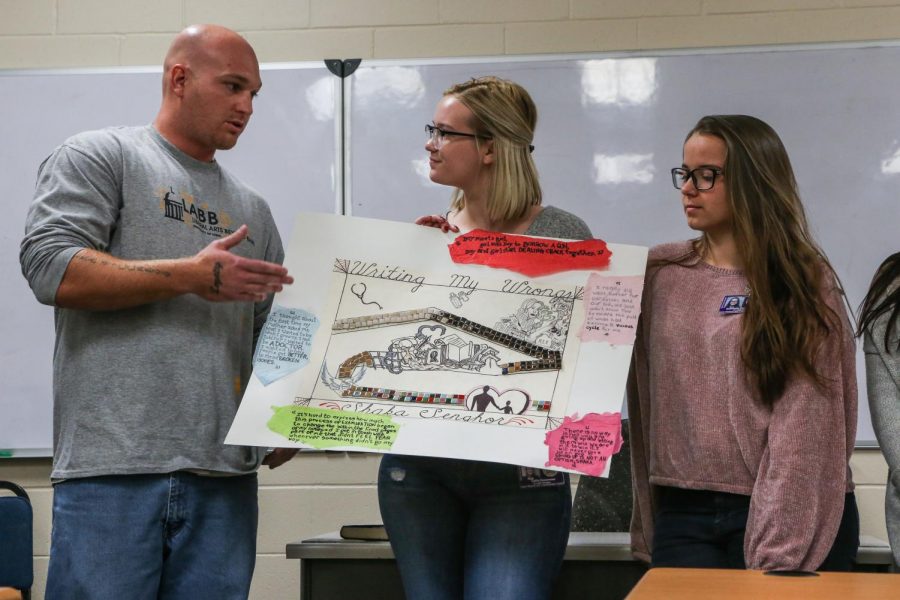

Students present a group project during a One Community, One Book class at the Oakdale prison on Oct. 25. The class is offered once a year through the UI Center for Human Rights.

UI students learn alongside inmates through college in prison program

The UI’s college in prison program, Liberal Arts Beyond Bars, continues to grow after its first-ever co-learning course.

November 13, 2018

The beige-wall classroom comes alive with noise as students arrive and form small groups, scattering throughout the room at long wooden tables to work on presentations.

One group puts the finishing touches on a poster as another group runs through a presentation. Books, papers, and markers are strewn across the wooden tables that line the carpeted classroom, which contains a single computer and projector.

The classroom has filled up quickly on this cool October evening with around 30 people gathered to hear the presentations.

Many are college students, wearing jeans and sweaters. Others seated throughout the classroom are older men wearing the same standard gray T-shirt, blue jeans, and sneakers assigned to inmates at the Iowa Medical and Classification Center, also known as Oakdale, in Coralville.

An unusual mix of people, to be sure. But this class — which brings inmates and University of Iowa students together once a week — is unusual. In fact, not many other communities, or even states, have anything similar.

The seven-week course, One Community, One Book, is an annual one-credit-hour course offered through the UI Center for Human Rights. This is the first time the course was offered at Oakdale as a part of the UI college in prison program Liberal Arts Beyond Bars.

The program is the first college in prison program at a public university in the state and the largest college in prison program serving the most students at a public Research 1 flagship university in the country.

RELATED: College prison program to bring undergrads and inmates together

Program director and course instructor Kathrina Litchfield begins to take the roll, and the boisterous group of students quiets down.

“Kaitlyn, Matt, Daniel, Callie, Wyatt, Zach, Michael …”

“Here,” Michael Blackwell replies as his name is called during roll call. The 49-year-old is seated at the back of the classroom.

He is serving a life sentence and has been in prison since 1991. He’s served time at the Iowa State Penitentiary in Fort Madison and the Anamosa State Penitentiary and arrived at Oakdale a little over a year ago.

He is one of 13 inmates, or “inside students,” enrolled in the course. The class is the first co-learning opportunity of its kind in which 12 undergraduate students, called “outside students,” from the UI campus go into the prison for class.

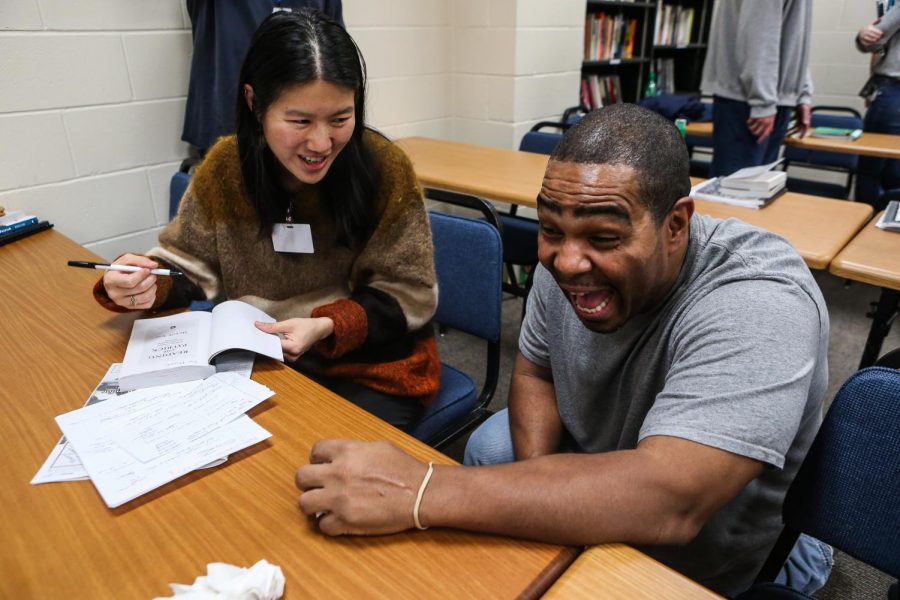

Together, the students have been doing a close reading of the 2018 One Community, One Book selection Reading with Patrick: A Teacher, a Student, and a Life-Changing Friendship, by Michelle Kuo. The reading program is a partnership between the UI campus and the community that aims to promote human-rights education through literature.

Through the reading, the class has focused on the theme “Redesigning the American Dream,” the theme for the UI spring 2019 semester.

With this theme in mind, the students work in small groups to analyze and create presentations over four main readings: The Fire Next Time, by James Baldwin; The Other Wes Moore, by Wes Moore; Our America, by LeAlan Jones and Lloyd Newman; and Writing My Wrongs, by Shaka Senghor.

Blackwell’s group read Baldwin’s book, and each student selected a quote to discuss in the presentation, focusing on amplifying Baldwin’s marginalized voice and perspective.

“This class has taught me how to stretch myself, how to listen to other people’s viewpoints and know that they’re valid, and not just think that my own way is the right way,” Blackwell said. “It’s opened me up on a deeper level than just class. It’s opened me up as a human being.”

Being a part of the class has not only changed his perspective, it has also changed the outside students’ perspectives of incarcerated individuals.

“It’s been enlightening to meet these guys and for them to treat us like humans and not like mistakes,” Blackwell said. “We’re students right along with them. That kind of restored my faith in humanity.”

UI junior Zach Lively said he had no idea what to expect initially — the class has challenged him and been a welcoming environment.

“This is an educational experience that most people never have,” Lively said. “This type of world is not in most people’s scope. Most people aren’t thinking about what happens in prisons, and I think it’s an important perspective that people should take a look at.”

Lively, an English and education major enrolled in the course, said he’s enjoyed hearing the perspectives of the inside students on the material they have been reading because they are so different from his own.

“It’s been a very humanizing experience for people who are incarcerated,” Lively said. “They’ve helped broaden my perspective, and the takeaway overall would be that everyone has experiences and stories that are vital and important to the larger narrative of the American Dream.”

UI sophomore Callie Hauerwas, an English major with a secondary education focus, said that like Lively, she was unsure of what to expect from taking a class in a prison. But being a part of it, she said, has been one of the best experiences she’s had at the UI.

“On our first day, we talked about our American Dreams and what our individual dreams are,” Hauerwas said. “While most people would talk about property, money, or making it big, these guys’ answers were about the want to find friendship, and to find community, and to see their sons graduate. It was just the most raw, human connection.”

Hauerwas said the bonds she has been able to form with the inside students have really affected her and challenged the stereotypes she had when she started the class.

“I pride myself on being pretty open-minded, but [this class] gave me even more of a chance to step in the shoes of people that I typically wouldn’t have,” she said.

Engaging in class discussions, completing homework assignments, and putting together group presentations has been a shift for the inside students participating in the program after having been away from education for years.

“It’s difficult after all this time,” said inside student Daniel Hicks, who previously earned a journeyman license in electricity before he was incarcerated. “To come back and do these types of classes was a little bit of a shock.”

The 42-year-old is new to the program — he started taking classes this past summer.

“I think the biggest thing is to feel human again,” Hicks said. “And the acknowledgment that we can do something with our time while we’re here in prison other than just do time.”

The program is just a year old. It piloted in the fall of 2017 with a noncredit speaker series in which nine UI professors volunteered to teach introductory courses to 33 students. This past spring, the program offered numerous classes for credit, including two speaker series, a yoga course, and participation in the Oakdale community choir.

RELATED: Oakdale Community Choir, “hope in the face of justice”

“There are tons of opportunities as soon as we recognize that this is a legitimate learning space,” the program’s director said. “Study after study after study tells us above treatment programs, above lengthening sentences, above seclusion, the most effective approach to reducing recidivism is education.”

As Litchfield looks ahead to the future of Liberal Arts Beyond Bars, her top priorities are building up the program to be financially stable and providing a path to bachelor’s degrees for the incarcerated students.

Program director Kathrina Litchfield facilitates a discussion among students during a One Community, One Book class at the Oakdale prison on Oct. 25. The session was the first opportunity for inside and outside students to learn in the same room.

Currently the inside students’ tuition is being covered by University College, which is one of the UI’s 12 colleges and is home to numerous programs. Associate Dean of University College Andrew Beckett said the college has funded the program with limited gift monies and is not using tuition or state aid.

When it comes to instructors of the program, most have volunteered and have not been compensated.

The program was awarded a two-year $150,000 grant through the Institute for Higher Education Policy, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization committed to promoting access to and success in higher education for all students, with a special focus on underserved populations such as incarcerated students.

With the grant money, program leaders are working on developing a budget and initially plan to use the funding to create two, two-year staff positions to help oversee the program and raise funds.

The new co-learning model that was tested with the One Community, One Book course was a way to generate tuition revenue from the classes being offered through the program. Litchfield said she would like to teach the course again and continue to use the co-learning model in other courses.

Along with applying for grants to help fund the program, Litchfield is also looking into partnering with Iowa Central Community College, which is involved in a three-year pilot program that opens up the opportunity for those who are currently incarcerated to apply for federal Pell Grants, a form of financial aid awarded to students with high financial need.

“This would be a huge win for us because our role would be to support the students but not incur the cost of instruction,” Beckett said in an email to The Daily Iowan.

Iowa Central Community College has developed degree programs online at the North Central Correctional Facilities in Rockwell City, Iowa, where incarcerated students can work toward associate degrees. Litchfield hopes to enroll her students in the online associate-degree programs through Iowa Central Community College and then transfer those credits to the UI so that the incarcerated students can work toward earning bachelor’s degrees.

“The University of Iowa does not offer associate degrees, but it is a really practical milestone for those who have spotty access to education and would like to pursue a bachelor’s,” Litchfield said. “It’s a huge step for us … because it means we can really streamline the program. We can work with students toward finishing degrees, which I think makes this program all that more valuable.”