The roots for students to flourish: After 50 years, Afro House remains necessary

The times have changed in the 50 years since the Afro House was established, but those who use the space say it remains necessary.

October 22, 2018

You could go days without seeing a black person around campus and Iowa City when Venise Berry was a University of Iowa student in the 1970s.

It was that sense of isolation compounded by the racial tensions of the times that prompted black students to call for a space on campus of their own — a space where they could come together, relax, and just “be” with people who looked like them — while living and learning at a predominantly white institution.

Amid the peak of the Civil Rights Movement, in 1968, the UI gave black students just that — a residential-style unit in the form of a house dedicated to serving them.

“It was ours,” Berry said. “It was a place for us.”

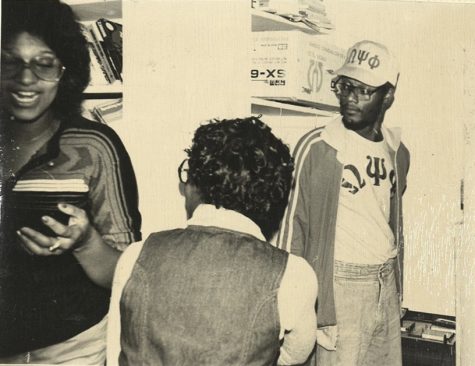

Then-UI student Venise Berry (left) is pictured with other students.

The first ‘home away from home’

1968 marked the year the UI started putting resources toward physical spaces in which historically marginalized populations could go to find others like them.

Now, 50 years later, UI has four cultural and resource centers that serve the Latino, Native American, Asian-American, Afro-American, and LGBTQ communities. They aim to affirm students’ identities and provide a place in which those students can feel a sense of belonging.

The UI’s centers stand among other public institutions, including the 14 Big Ten schools, which also have centers dedicated for historically marginalized populations on campus.

Each of the UI’s centers was founded for different reasons and in different ways, said Prisma Ruacho, the Asian Pacific American Cultural Center coordinator.

But the Afro House was among the first cultural centers in the nation to be established, serving as a hub for student activism during the Civil Rights Movement.

“We wouldn’t be here without that first step,” Ruacho said.

That’s precisely why the university community recently hosted a celebration for the Afro House to honor its 50-year history, she said.

Students had to fight to secure that place to call their own against pushback from administrators, Afro House coordinator Jamal Nelson said.

Then came Philip Hubbard — the vice president for Student Services and dean of Academic Affairs at the time and also the first African American vice president at a Big Ten university. Hubbard helped black students on campus secure a temporary location for a center at 3 E. Market St., which opened in October 1968.

Plans for a center for black students on campus came at the recommendation of the UI Human Rights Committee in 1967, The Daily Iowan reported in November 1968.

The center would especially serve black students, Hubbard said then, where they could express themselves through literature, art, music, poetry, and plays.

“The center is not just a service to the Afro-Americans but to the entire community,” Hubbard told the DI in 1968. “In many places, there is a general ignorance about Afro-American culture in general. The center is an opportunity to educate the entire community.”

Hubbard told the state Board of Regents in 1970 that the survival of black students could be attributed to the center’s existence, allowing students to share a common heritage and come together.

“Although it is difficult to separate the social, academic, spiritual, and recreational aspects of its operation, everyone who visits the center is convinced that it is a great asset to the university community,” he said.

By 1976, the center had moved from 26 Byington Road to its current location, 303 Melrose Ave. The other three centers sprang up in the following decades on the surrounding streets — one in the 1970s, and two more in the 2000s — forming a cultural corridor on the West Side of campus.

The center was established before Berry — now a UI associate professor of journalism and African American Studies — set foot on campus.

But Berry remembers studying at the center, participating in game nights, watching movies, and dancing.

“The floor would do this,” Berry said, smiling as she waved her hands up and down to mimic the Afro House’s floor’s motion under her feet. “It would be bouncing.”

Most of all, she said she recalls the bond she shared with her peers who frequented the Afro House.

“We were friends with other people,” she said. “But we maintained a really strong sense of unity, a really strong collective presence where we felt a place where we kind of belonged.”

Centers needed then and now

Those who work with the centers say they remain as necessary now as they were 50 years ago.

UI senior Arika Allen, who grew up in Davenport, said she struggled to immediately feel a sense of belonging on campus her first semester before she started visiting the Afro House.

As Berry did, Allen said she enjoys studying and hanging out at the center. She knows there’s always a place where she can go to find the support she needs.

“Once you step into the Afro House, it’s like, ‘I’m home. I can relax. I can be myself,’ ” she said. “I felt that the minute I stepped through the door freshman year.”

UI student Arika Allen speaks during the 50th anniversary celebration at the Afro American Cultural House on Friday, Oct. 19, 2018. Allen researched and designed a series of posters celebrating the history of the Afro House.

UI Assistant Director for Multicultural Programs Tab Wiggins, who oversees the centers, said she has seen a renewed focus on the spaces under the current university leadership. Funding for the cultural centers in the last five fiscal years has generally trended up, serving as a reflection of the university’s commitment to supporting diversity and improving the campus climate.

Inside, the centers’ walls are decorated with culturally relevant art. The spaces include kitchens, couches, tables, bathrooms — all providing a livable “home away from home” atmosphere for students to enjoy.

When UI President Bruce Harreld started at the UI in 2015, he recently told the DI, he thought the university hadn’t really taken care of the centers. Harreld said he visits the centers several times a year to check in and see what else the university can do to help.

“… I keep saying to each of the members of each of those communities, you need always have a sense of being able to get into a room where you’re full of people just like you, and they understand what you’re going through, and you can relate to, and you can have the conversations and get the support that you need,” he said.

*General expenses are for things such as campus programming, student employment, and any general maintenance of the centers, with most of the funding going toward student employment. (Source: University of Iowa)

The elevated spotlight on the centers also stemmed in part from community conversations that occurred with those identity groups during the fall of 2016 led by Harreld and former UI Student Government President Rachel Zuckerman.

In the summer of 2016, before those community conversations, the UI updated and renovated the centers, completing basic landscaping, upgrading office equipment and furniture, and adding new computers and printers.

Recent updates include:

•New window treatments in LNACC, Afro House, and APACC

•Upgraded portable air-conditioning units in Afro House and LNACC

•Upgraded security (cameras and new locksets) on all houses

Additional resources beyond that have been provided in recent years to support full-time staff positions at each center and programming for events, namely heritage months.

In 2016, UISG also implemented a stop at the cultural centers on the Cambus Interdorm route to provide students with an easier way to access the centers.

The coordinators said despite the additional funding and support, it remains a challenge to address the community’s needs with the resources available to best serve the campus.

“I don’t know anyone else who’s on campus that has historically been continuously celebrating these different folks …” Nelson, the Afro House coordinator, said. He took note of university councils that do some programming, but, he said, those are still connected to the centers. “It’s a hard bargain when they want us to do all those programs, but we don’t get all the funding to do all those programs, and knowing that what we do has a large impact on each community that we serve.”

Looking from the past into the future

There’s a strong foundation in place for the centers, but there remains a ways to go, officials say, to further improve the physical spaces themselves and address the issues facing the people who use them.

“What they did 50 years ago, what they dealt with 50 years ago, we’re still dealing with in 2018,” Nelson said. “The center’s still here to be a home, and to be a facilitator of those discussions, and to be a space that our students can call a safe haven from everything else.”

For centuries to come, Wiggins said, she anticipates people will need to continue doing this work to help widen the university’s embrace of multiculturalism.

“Our idea is to integrate multiculturalism and cultural responsiveness into the entire fabric of our institution, to institutionalize our ideas and our mission into the rest of campus,” she said. “But that’s not happening. That’s the goal, but we are still fighting against racism, and patriarchy, and heteronormativity.”

Posters and graffiti with racist, homophobic, and anti-Semitic messages on them have been found around campus in the last couple of years, a cause for alarm for those at the UI who advocate for underrepresented students and strengthening diversity.

Institutionally, Wiggins said, the university has made strides in recent years to address some of its struggles with diversity, such as recruiting and retaining diverse faculty, but she feels there’s room for improvement.

According to the UI’s January report on diversity, equity, and inclusion, only 7.4 percent of full-time tenured and tenure-track faculty are underrepresented minorities, meaning minority students are less likely to be taught by someone who looks like them.

“With all those things still at play, we’re going to be doing this work forever,” Wiggins said.

And representation of black students in the student body hasn’t increased much since 1978, the year UI enrollment by ethnicity was first documented. That year, 2.5 percent of students were black. In the fall of 2017 — with enrollment having increased by more than 10,000 students since 1978 — African American students only made up about 3.1 percent of the student population.

While the university promotes its diversity well before people get here, Allen said, it can be more of a challenge to get connected to the resources needed to succeed once people arrive.

“Don’t use the centers as a poster child, but try to figure out what the students at those houses need,” she said. “… If you’re going to say you’re a diverse university, you have to follow through with that diversity.”

As for the centers themselves, Harreld told the DI in 2017 that the administration and UISG discussed further improvements that could be made with the cultural houses. Adding lighting and paved walkways in the cultural corridor are possibilities he mentioned.

Many people seeking to use the centers identify with numerous affinity groups, and there are no rules about who is allowed to enter the houses. To create more of a sense of community, Harreld recently told the DI, the UI has larger aspirations for the centers, including the possibility of creating a common house or a kitchen for larger gatherings.

“I think at the end of the day whatever we can do to make students feel more comfortable when they’re not in class and identify with groups that they want to hang out with,” Harreld said in 2017.

Allen, who was involved with some of the 50th anniversary celebration efforts, said she found a quote while examining the center’s history that has appeared on items the Afro House has used over time: “Just as a tree cannot stand without its roots, a people cannot stand without their culture.”

And to her, that’s what spaces such as the Afro House provide — the roots to flourish.

“You need those roots, you need that ground,” she said. “You can’t go forward if you don’t know your past.”

A poster celebrating the history of the house during the 50th anniversary celebration at the Afro American Cultural House on Friday, October 19, 2018.