From Iowa to Israel: The search for my Jewish identity

On a free trip to Israel with fellow Jewish college students, a DI reporter prayed to find a sense of belonging.

September 25, 2018

After one too many tequila shots, Monica woke up in the same state she had been the night before: drunk. My friends and I noticed her drunken stupor after her purchase of a small drum with “Jerusselm” misspelled on its front. The walk — more like a hungover shuffle — to the stone gates of the Old City was not as quiet or riveting as one might expect, because Monica decided that banging on the drum while singing the “Walmart yodeling kid song” was the proper way to greet the holiest city on Earth, Jerusalem.

Birthright, a nonprofit organization, gives a free trip to young Jews around the world to help them connect with Israel and their Jewish identity. Even as grateful and connected I felt to such a place, I found Monica’s perfect pitch amid the sand-dusted gates of the city to be the most suitable background music for my current place in life.

The trip also allows us “cashews” (one parent Christian, the other Jewish) to join the incredible journey.

My name is Madison Lotenschtein, and I am a certified cashew. I was born in Hawaii and raised in Iowa. No, I am not Hawaiian, and my last name isn’t German, just to set the record straight. I was brought up in a Christian/Jewish light that accepted other religions and ways of life because of the diversity in our four-walled Victorian home. Growing up and having a Jewish identity in Iowa is a subject I have yet to discuss with anyone. My father is reform. In other words, a fairly liberal Jew.

While it was daunting enough to land in a foreign nation, it was even more frightening to think of being schlepped across a country with 40 strangers near my age. After all, this was my first time traveling without my family. We were all hoping to enhance or find our Jewish identity, whether it be by joining in on the “Walmart yodeling kid song” or by praying on the Western Wall.

The Jewish entrance to the Old City of Jerusalem was built of stone and nesting pigeons, mottled with bullet holes of wars previously fought. A grand tunnel led tourists, civilians, and soldiers into the city; ancient murals hung on its chalky walls, excavated and cleaned by those who held much more patience than I.

We were escorted into a vibrant courtyard, where beams of sunlight reached down and stroked every head while children played ball on the sun-dried cobblestone I still slipped on. Monica, my wasted companion, ceased her music-making once our tour guide motioned for everyone to sit on some thousand-year-old steps.

Were these steps actually more than 1,000 years old? Absolutely not. The Jewish Quarter had been demolished in 1948, wiping away the ancient homes and buildings. Following in their ancestors’ footsteps, the Jewish people wiped their tears away and started rebuilding.

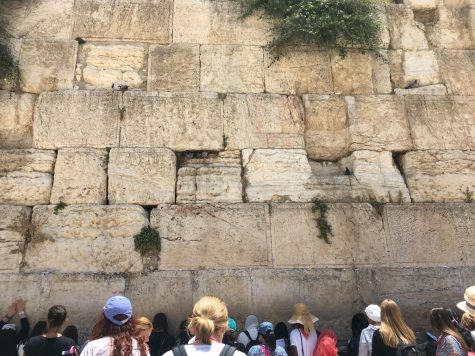

Where does the water flow in Israel? The Jordan River or the tears of those praying on the Western Wall? I chose the latter in hopes their dried and cracking souls are watered with answered prayers. The Western Wall is considered one of the holiest sites in Judaism. It is believed that your prayer will be answered if you write a note and place it in the cracks of the Wall, so I just had to make a few dreams come true. No Jew visiting Jerusalem would ever pass up such an opportunity.

While I made the jaunt back from my designated section of the Western Wall, I thought of Enjolras’ statement from Les Misérables, “Is your life just one more life?” and replaced it with “Is my prayer just one more prayer?”

The other three quarters of the walled city belong to the Muslims, Christians, and Armenians. The Armenian quarter was the smallest of them. A trek of fewer than 10 minutes allowed all of us to cross the alleyways of stray cats and potted plants back to the bus. I couldn’t help but feel sorry for the Armenian minority. Its genocide, conducted by the Ottoman Empire in 1915, has been forgotten by many, and only 3 million Armenians remain from the abhorrent blow to their ethnicity.

Traveling from a many-century-old city to the first modern city of Israel, Tel Aviv, consisted of a battle between American pop music and Israeli pop music. I was one of the lucky few to be sitting in the middle of the two musical administrations. Is this what it feels like voting for the third party? In time, the racket was subdued by a loud complaint from an outlandish few while our bus roared past the sand-dusted hills of the Holy Land. Thousands of rocks were scattered about the hills, as though a massive toddler with an enormous temper had thrown all of them astray. Our arrival in Tel Aviv was painted with sweat, smiles, and of course, all the colors of the rainbow: It’s Pride Day. All in Tel Aviv were celebrating, and swarms of people weaved in and out of my group.

“TagLit, TagLit, TagLit.” The cheer was shouted from balconies and from the multicolored confetti-strewn streets below. Taglit is the nickname for Birthright, which translates to Hebrew as “discovery.”

Our group of students was full of East Coasters, most of whose stomping grounds was in Queens, New York. “What is there to do in Iowa?” they asked, their brows scrunched in curiosity, “How many Jewish kids did you graduate with?” I replied with my pre-recorded response, “I was the only Jewish kid in my graduating class of 129, and my dad still practices law in a different state because A) he refused to take the bar again, and B) he didn’t want to be the only Jewish lawyer in town.” I always manage to get a few laughs out of that one-liner.

However, there were times where I felt like less of a Jew than others on my trip because of my mother’s Christian background. I know many biblical stories but almost made a fool of myself after ascending Masada, a cliff of that overlooks the receding hairline of the Dead Sea. One of the cliff’s leading poster boys of history is King Herod the Great. Ah, that name rang a bell. “Isn’t he the guy who almost killed Jesus?” I nearly asked. I quickly remembered that there is no sequel to be discussed on Birthright.

There were also times where I felt like my “Iowa Nice” culture clashed with the shoulder grazing, line budging, and acute bluntness of the local Israelis. Israel lacks the usual Iowa phrases of, “I’m going to sneak right past ya” and “Hi, how are ya?” but the country makes up its off-putting manners with pure honesty, genuine conversation, and absolute love for their music and food. Falafel is an Israeli/American favorite consisting of mushed up chickpeas molded into balls with hummus, cabbage, tomatoes, and cucumber wrapped snugly in a tortilla or pita bread. I could waft in the savory smell the minute I stepped into the shade of the vibrantly colored markets. While I couldn’t barter down the price of a falafel, I tried my hand at bartering down an overpriced bracelet. As my Queens buddies would say, “You just got clapped.” (I just got screwed over.) Israeli Life = 1. Iowa Nice = 0.

After such a failure, feelings of inadequateness began to settle in my stomach: Did I really belong to such a crowd? I couldn’t barter; I didn’t speak Hebrew; my mother is a Christian; and I had only practiced Friday night Shabbat a few times in my 19 years.

I believed my warped thoughts until I sat next to a rabbi on our flight from Brussels to New York. Once he finished complaining about the horrible kosher airplane food, he explained to me how being Jewish and acquiring that identity no longer requires Jews to live in crammed ghettos, speak Yiddish, or huddle together to wince at the crack of mass anti-Semitism whip; being Jewish now takes a more personal form, one that can be practiced and expressed through one’s self. What matters is that we all can form our own individual identity of what being Jewish means to us. But that doesn’t mean there is a lack of firm plateaus in the Jewish-American community. The phrase, “They can take everything away from you, but they can’t take away your education” is like a knife used often but whose edge never alleviates. It’s recognizing that there are firm ties between you and your Jewish family and friends. It’s a whisper from the breeze of the Israeli desert, a sense of belonging, one that grants my prayer, my hope of acceptance, to come true.