10 years later, the collective memory of the 2008 flood remains

In 2008, the UI learned some lessons about irresistible force and immovable objects when floodwaters submerged campus.

June 13, 2018

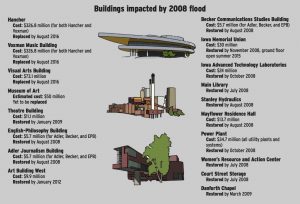

Predicting floods is incredibly complicated and not terribly accurate. In June 2008, this came at a high cost to the University of Iowa when a 500-year flood damaged over 20 buildings, some too badly to fix. To date, $700 million has gone into repairs, refurbishments, and replacements to campus.

Looking forward, local experts are confident floods are happening more frequently. But the community is a lot more prepared than it was in June 2008 to deal with rising waters.

UI hydraulic engineer Larry Weber said different land use and climate patterns of today negate comparisons with data collected 100 years ago. In other words, he said, the way water cycles through the environment is simply not the same now as it was then.

Using newer approaches that consider these factors, in fact, Weber said a 500-year flood, like the one in 2008, is more like an 80-year flood — meaning in a given year, there’s about a 1.3 percent chance of it occurring.

“We have these standards … that we don’t think accurately project the likelihood of flooding,” he said.

Lessons were learned in 2008, better preparedness plans have been implemented, and the recovery provided an opportunity to create a more resilient campus. Many community members remember the floods, the recovery, and the rebuilding. But many thousands of students in particular have no memory of classrooms, dorm rooms, and art studios underwater.

A collective reminder of the flood persists 10 years later, in new buildings, mitigation efforts, and the capricious, temperamental river dissecting campus.

The Pearl of Iowa City’s Oyster

Hancher Auditorium, slated to host the Chicago-based Joffrey Ballet and musicals such as Spamalot and Avenue Q in its upcoming season, helplessly stood on the west bank of the Iowa River as predicted floodwaters inched into the 36-year-old building, putting the famous Hancher stage under 18 inches of water and submerging rows A through O of the 2,500-seat theater.

Ten years later, Hancher Director Chuck Swanson says he will never forget the moment he entered the waterlogged auditorium and how he thought it would take at least a year to fix up his “home away from home.”

He had no idea at the time that the building was beyond repair, and for eight years, Hancher would be a nomadic operation.

With no stage to perform on, Swanson unveiled the theme for the 2008-09 Hancher season — ”Can’t Contain Us.”

“We decided as a staff that we were going to take a positive outlook on this … and that was the best possible thing we could have done,” Swanson said. “We told everybody to stay tuned, because we would have to make decisions about the upcoming season.”

He and his colleagues sat together on the Pedestrian Mall on a summer day in 2008 and ran down the list of Hancher’s upcoming shows, deciding which ones could happen and which ones couldn’t.

About half of the shows were canceled because there was no stage in town big enough to hold them. The rest of the performances were taken in by local high schools, the Englert, and other facilities.

“Little did we know that we’d be doing that for eight years in the future,” Swanson said.

Now, Hancher sits 13 feet higher on the same bank of the river. The lustrous structure of glass walls and spotlight-decorated wooden ceilings is shaped like a mighty ship, seemingly invincible to the inevitable floods of the future.

The ugliest building in the state

Unlike Hancher, the English-Philosophy Building, built in 1966, is not adored by the community. Once deemed the ugliest building in Iowa by Business Insider, EPB survived the damage inflicted by the flood and reopened for classes in August 2008.

“We all were hoping they would just condemn the building and replace it because we all famously are dissatisfied with it, but we also have sort of an affection for it as well,” English Professor Loren Glass said.

Glass served as the chair of the English Department that summer. A native of California, he recalled the surrealism of the “slow-motion disaster,” much different from the natural disasters he was accustomed to, such as earthquakes.

“It was sort of strange because people would call and be like, ‘Are you OK?’ ” he said. “If you’re not right on campus, you’re not aware there’s a disaster occurring. You knew it was happening, and then we waited to see what happened, and then once it happened, it was still very sited [by the river].”

‘The last remaining casualty of the flood’

Lovers of art are still waiting for a home for the UI’s $500 million art collection, including Jackson Pollock’s Mural, that has toured the world for the last decade and is currently on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Facilities Management Director Don Guckert called the Museum of Art “the last remaining casualty of the flood,” because all other recovery is complete.

The old museum did not get damaged enough to receive funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency for a replacement, as did Hancher, Voxman, and the old Art Building, so the construction of a new $50 million facility relies largely on donations.

Construction on the new museum, which will be located above the parking lot just south of the Main Library, was put on hold when UI administrators announced a moratorium on all campus construction in April through Sept. 12 in the midst of state budget cuts amounting to $5.5 million. Officials now hope to begin the process of bidding and construction in the fall.

RELATED: UI halts campus construction to cope with midyear budget cuts

But the museum stays alive despite not having a brick-and-mortar location. The collection is dispersed among the IMU, the Figge Museum in Davenport, and around the country as a traveling collection.

Mark Seabold, the past president of the Museum of Art’s members council, said the challenge of operating without a facility forced the museum to focus on outreach, sharing the collection around the state. And the delay, Seabold said, will just make it sweeter when the new museum finally opens its doors.

“Seeing all the other buildings go up is hard, but as soon as it goes up, it’s going to be the biggest party ever,” Seabold said.

The human chain

Because of fears that floodwaters were going to inundate the basement of the Main Library and damage items from Special Collections and elsewhere, on June 13, 2008, two days before the river crested, a line of 200 volunteers formed to move 50,000 books and material to higher floors by passing them one at a time.

Hours went by before Facilities Management’s Guckert decided it was getting too dangerous for volunteers to stay in the basement much longer. He knew the polluted waters were just hours away from seeping in. He decided to give volunteers until 5 p.m. to get as many books out as they could.

He remembers announcing over the PA system that volunteers had just two hours left.

“I thought there was going to be a groan, but there were cheers and applause,” he said. “It was just the passion and the emotion of people wanting to do what they could to do their part.”

Though the library basement ended up only flooding about 3 inches, Nancy Kraft, the head of the UI Libraries Preservation and Conservation Department, said the bottom 3 feet of materials were brought to safety thanks to the human chain.

Work continues to salvage damaged books

In Iowa City, virtually no books were lost to the flood in part because of the human chain. Cedar Rapids was not so lucky when the Cedar River flooded virtually overnight on June 10, 2008.

Books from the Linn County Recorder’s Office in Cedar Rapids are finally getting the mud scraped off their pages and receiving new bindings from the UI Libraries Preservation and Conservation Department.

The mortgage records dating back to the 19th century were freeze dried after the Cedar River flooded the office, located downtown Cedar Rapids one block from the river. As low-priority records, these 450 1-and-a-half-foot-tall books are the last of the department’s flood-recovery efforts. Each book takes an average of six hours to clean and rebind, and in two years, a team of a conservator and two students have finished about a quarter of them.

In the wake of the flood, the UI Libraries Preservation and Conservation Department took in such materials as books, baskets, textiles, and photographs from the African American and Czech Museums, also located downtown Cedar Rapids.

Kraft remembered the obnoxious smell of river sludge as items came into the lab.

“It was pretty scuzzy work,” she said. Workers had to wear masks and gloves to handle the materials, and even had to bring an environmental-safety official to ensure workers were protected from the growing mold, as items had to be kept wet to best preserve them.

In the aftermath, the Iowa Conservation and Preservation Consortium, based in Iowa City, created a statewide team that can respond to disasters such as this much more quickly than in 2008.

“What we realized is by having a group of trained people at the gate, we are able to save so much stuff,” Kraft said.

Professionals of disaster

In the world of performing arts, things often go wrong. Pianos can be out of tune, stage props can break, and in the case of the UI Division of Performing Arts, buildings can flood.

Voxman Music Building, at the time attached to Hancher, and the Theater Building both suffered massive damage, so the music and theater communities were taken in all across town, from university buildings to local churches.

Administrator for the Division of Performing Arts Kayt Conrad said, however, this was the best group of people the disaster could have happened to.

Despite whatever may happen, she said, “you still have to go out and cheerfully put on a good show for the audience. So these people are kind of professionally prepped for disaster.”

Conrad remembered the challenge students and faculty encountered playing music and dancing in places that were not designed for that.

One time, actors were practicing in a room above Devotay, and the vibrations from their movement knocked over an entire shelf of glasses.

“We’re just not good neighbors,” Conrad said.

Filling a need for flood research

Hydrologists at the UI such as Larry Weber and Witold Krajewski did not focus their research on Iowa before the flood.

That changed shortly after.

Weber and Krajewski founded the Iowa Flood Center with annual funding of more than $1 million from the state Legislature to serve as an as an academic research institution aimed at better understanding floods in Iowa. Since its creation in 2009, the center has made live flood information available online to inform the public of flood risk statewide.

In Iowa City, flood risk is largely determined by water levels in the Coralville Reservoir, managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Construction on the reservoir began 69 years ago about six miles north of campus, and engineers regulate the water level behind the dam to protect downstream communities from flooding. If the dam overflows the emergency spillway, the waters gush toward Iowa City. This has happened twice — once in 1993 and again in 2008.

“In 60-plus years, twice we lost ability to control [the dam’s] releases,” Krajewski said. “So twice in 60 years? Maybe three times in 100 years? These chances are real.”

The frontline of protection

This year also happens to mark the 25th anniversary of the 1993 flood, a 100-year flood event that became the benchmark for the UI’s flood response plan. As the waters in 2008 rose higher and higher, Guckert soon realized the plan was too little, too late.

“It was Mother Nature’s battle,” he says now. “She won it.”

The lesson learned, he said, is that the next flood will be bigger.

“We’re not going to make that mistake again, to think that we just need to prepare for our last flood. We’ve got to prepare for the next one, which unfortunately appears to be more and more severe these days.”

New buildings have been constructed several feet above the 500-year flood line. The IMU is now protected by flood walls disguised as a terrace and concrete benches. A warehouse off-campus stores pumps, generators, and barriers that can be assembled on the banks of the river if floods are forecast. In fact, these barriers have gone up twice since 2008 when threats came in 2013 and 2014.

The university isn’t planning any events or acknowledgment for the 10-year anniversary of the flood.

“I think it’s good that we’re reflecting after 10 years, but it’s time to move on,” Guckert said. “There’s a whole generation of folks who weren’t around, and I think those of us who were, we’re ready to put it behind us.”