The tank is intimidating when I’m led through the Iowa Recovery Room and to the place in which I’ll be isolated for the next hour.

The door looks more like a hatch. The whole thing comes across as very galactic, as if I am about to be transported or locked inside for safekeeping, like a specimen in a jar.

Samahdi, it reads, on the surface of the tank. I strip down and touch the words as I step inside. It’s an ancient word, from Sanskrit, that signifies the state of intense concentration achieved through meditation, a mental state that Hindu yogis consider the final stage in reaching union with the divine.

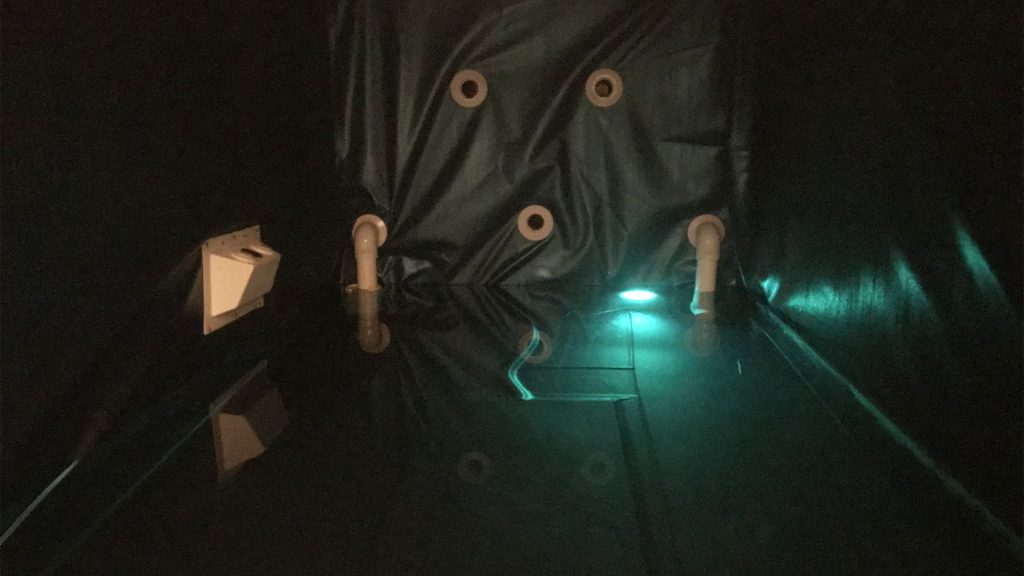

The Iowa Recovery Room is owned and operated by Patrick Krier, and he tells me that Samahdi isolation tanks were the first ones to be designed, to perfection, for commercial use. They are catered entirely to the experience of sensory deprivation, of leaving one alone with nothing but 10 inches of water and 800 pounds of dissolved Epsom salts, with the feeling of true weightlessness and the forced understanding that when nothing exterior can determine our actions, it is all up to the mind.

The hour I spend in the tank fluctuates through a series of different self-created realities, some kinder than others. I’m vaguely able to understand what is happening in my mind as random songs, snippets of conversation, images, lights, and inertia come and go with my breaths. Pieces of remembered experience do their best to inform the one I’m having now, but it’s no use.

My mind takes a detour in to the future at one point, wondering what words might help me explain this experience. But I entered the tank with the intention to be perfectly present, and the present moment continually makes it clear that I have never experienced anything analogous to sensory deprivation.

I have a background in meditation, and sometimes, trying to tame my thoughts, I’ll imagine what my body would look like compared to nothing. As I breathe, I ask, How big am I? How small? If I were standing in an infinite world of white, how would I even comprehend my own body? And without my body, what would I be left with?

In 1953, when American physician John C. Lilly began the experiment that would result in Samahdi sensory-deprivation tanks, he tested similar questions, wondering what happened to the human mind if you remove the stimulus of the outside world. The predominant, Western school of thought was based on the behaviorist school and guessed that with no stimuli, relieved of its duty to reality, the brain would simply give up. One would enter a comatose, unconscious state. A dreamless sleep.

There are only a few moments when I am entirely grounded in the physical reality of being in the tank, in the farthest room on the left, in a building adjacent to a law firm, in Iowa City. These are the moments that my body jerks, as if I’m waking from a dream, though I’ve been perfectly aware of the trajectory of my thoughts, as strange as they seem. I open my eyes to more blackness, quiet my thoughts to absolute silence, and am met by mellow ripples of water that rock me endearingly.

My toe touches one of the walls. I push off, lightly, back in to what feels like an ocean of open water, “deader than the Dead Sea,” as Krier put it.

Between that waking reality and sleep, I spend the hour in a sort of lucid dream, coming to terms with the fact that my body and my mind are entirely alienated from one another. Lilly’s alternative hypothesis to the behaviorist school becomes my reality, and my mind continues to operate, to confound me. It settles on the understanding that I’m nothing but a blissful blip of existence. And so, I simply exist.

There are moments when some shift in my stomach registers as a weird, underwater sound in an otherwise silent space, and even then, the noise is foreign, exterior, not created by my mind, and therefore, not relevant. It’s easy to forget that I have a body at all. There’s only the tiniest bit of water tension to remind me what is up and what is down, and soon that seems to disappear, too.

My mind tries to remedy this confusion. It feels as though I am spinning. Sometimes in a circle to the left, sometimes in a circle to the right. Sometimes, it feels as if my whole body is sinking downward from my head, and I am doing backflips. At one point, I’m sure I’m lying on my stomach, but one deep breath makes me bob like a buoy and sets my brain straight.

Moving becomes profound. I reserve it for the moments when I most need to know that I can, in fact, still spread my legs and arms in to a star pose, can bring my fingertips to my stomach, the skin there slimy with salt water that I think for a moment might be sweat.

And when the tank comes alive with a dull hum, circulating the skin temperature water and cuing me that the hour is up, I hold on to the sanctity of my ability to control this body that feels separate from who I am.

I sit up, astounded when my lower body sinks to the bottom of the tank and I’m suddenly on solid ground again, barely submerged at all. Floating, the water feels endless.

I put my hands on the sides of the tank and find the button for a dull blue light I had opted to leave off. I look at my body, which I opted to leave unclothed, and I feel beautiful. I feel calm. I feel like I have more power over the word “I” than ever before.

When I first arrived at the Iowa Recovery Room, I was wary of the front door’s sign to remove my shoes. After my float, Krier’s serene smile made more sense, beaming out from behind the front desk.

He has hoop earrings and speaks with respectful reserve. Before I got in the tank, it was almost jarring the way he left spaces in his instructions, conversed slowly, so that I couldn’t tell if he had more to say after each sentence.

But now I feel that I’m in on something, on all the unspoken sentiments he left hanging between us as we talked.

When I go home and research the Samahdi tanks and their history, I begin to understand what exactly that intangible was between us and why I had such a greater appreciation for it after floating.

Practitioners of Lilly’s floating methodology are given specific instructions to not overly instruct. To leave the floater with the simple experience of floating, wherever it may lead them. The only underlying constant is the constant of consciousness, the fact that even with all our other senses deprived, it remains.